All of 13 years of age, in 1930 my father left his family farm in Saskatchewan, leaving behind his mother and five siblings — his father had died when he was three years of age — set to ride the rails for the next 9 years, alighting in the Annapolis Valley in the later summer to pick apples, working in every province across Canada, for no more than a meal and a roof over his head at night sleeping in a barn, more often than not taking shelter in a hobo camp somewhere adjacent to the railway tracks that span our nation, undernourished always, starving at other times, my father having joined a homeless generation of Canadian youth scrambling to stay alive in the midst of the Dirty 30s, doing the best that they could.

Until, as my father told me one autumn afternoon, sitting at his kitchen table …

“In early September of 1939, I was living in a hobo camp on the outskirts of Revelstoke, on my way to the Okanagan to pick apples. There was talk in the camp that something was up in Europe, that the German Army had invaded Poland. On September 10th, I was in town looking for food out back of a restaurant when I heard a bunch of kids, saw them running down the street, screaming into the air, “We’re going to war. There’s a war. We’re going to fight those dirty …

Next thing I knew, there was a hand on my shoulder, a man in a uniform. “Son,” he said to me, “we’re at war now, saw it comin’. I’m with the Army recruitment office just down the street. Why don’t you come with me, and we’ll get you all signed up. Three squares a day, a nice clean uniform, and you’ll get to see the world. No more living in hobo camps for you.

So, I did, I went with him, signed up. For the first time in almost a decade, things were looking up. After I signed my name on the dotted line, the sergeant handed me an army uniform, saying, “Find a place to put this on.” I ran back to the hobo camp, more excited than I’d been in I don’t know how long. There was a pond nearby the camp, I stripped off my tattered old clothes, jumped in the pond, got myself nice and wet, dried myself with my old clothes, and set about to get dressed up in my spanking new uniform. I don’t think I’d ever felt better in my whole life.”

In 1945, returning members of our armed services were more than a little excited to be returning home

My father remained a private in the army for the next six years — having a Grade 1 education, and being unable to read tends to inhibit one’s advancement — before returning home with all of the other troops in the late summer of 1945, arriving in the port of Halifax, from whence he’d set off to fight the war six years previous.

My father, Jack, had heard much about life in Vancouver from those he’d served with overseas, so chose to make his way out west to build a life for himself.

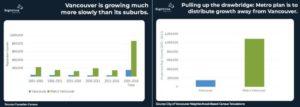

Prior to the outbreak of World War II, 83% of Canadians lived in the rural areas of Canada, mostly as members of farming families, leaving only 17% of the population to reside in hub cities like Montréal, Toronto and Vancouver, with much lesser populations in the prairie cities, and provincial capitals. On the Lower Mainland, Richmond was called Lulu Island, and was largely a farming community, as was the case in what we now call the suburbs: Coquitlam, Surrey, and Maple Ridge,

Almost overnight after the war ended, the rural-urban mix in Canada was reversed.

Berlin, post WWII: Statisticians calculated for every inhabitant there was 30 cubic metres of rubble

Following the end of the conflict overseas, with the industrial heartland of Germany, not to mention a great swath of Europe, and the production capitals of Japan leveled by the ravages of war, North America soon became the industrial heartland, and the bread basket, for the world. There were jobs aplenty across the North American landscape, as the U.S. & Canada became industrial powerhouses.

Most soldiers arriving home from Europe, rather than choosing to return to the farming communities from whence they had come prior to the outbreak of the conflicts in Europe and Japan, moved to the cities to make their fortune, many of them choosing to marry. Thus began the much vaunted baby boom, of which this writer is a member, born in 1950, and modern society as we still know it today.

Prior to the 1930s, most rural towns and cities across North America had within their midst indigent, homeless populations, but these were folks who were generally well known in their communities, boys who became men, men who’d lost their way and turned to alcohol to numb their pain. The homeless in these towns, and even in our cities, were well cared for by their contemporaries, who’d gone to school with these men many years prior, knew them from the time they were boys.

In every society throughout history, dating back centuries, there has always been 4% of the population who find themselves locked out of conventional society, women and men alone and without resources, perhaps suffering from some mental health disability, mostly uneducated, alone, without family or resources, and as conventional society would state, without the “spunk” that would help them to lead productive lives of meaning, to be part of the conventional work-a-day world.

The Raymur Housing Project, just south of Raymur and East Hastings — social housing in Vancouver.

In the 1950s, in perhaps a more empathetic time, when we actually cared for one another, provincial government social planners spanning the nation, in concert with their federal government counterparts, set about to house the homeless by creating “urban social housing complexes” to house the provinces’ poorest citizens, who would be brought to the city. In doing so, Canadian provinces adopted the multiple family dwelling, or “apartment”, model as the housing form to shelter the indigent population. In U.S. cities like Detroit, we are much more apt to call these “urban social housing complexes” by a more colloquial name: ghettos.

The Regent Park social housing community in Toronto, which expanded from the south Cabbagetown community in the Toronto of the 1930s, long one of the city’s worst slums, targeted by Toronto city planners for a grand urban renewal in the 1950s and 60s, which became known as Regent Park South.

As above, in Vancouver, the new community to house the poor was named The Raymur Project, where residents from across British Columbia were brought to Vancouver to live in the newly-conceived urban social housing complex.

Such projects, whether in Canada or the United States — in Toronto, Vancouver, Chicago, and New Orleans — proved abject, crime-ridden encampment failures.

Still and all, the homeless were off the streets, with a roof over their heads, pretty much hidden away from the eyes of conventional society, a forgotten population most people didn’t want to see, acknowledge or engage with on any level.

And so it remained through until the early 1980s, as we wrote on Tuesday.

An interview with Premier-in-Waiting David Eby, conducted by CBC Early Edition host, Stephen Quinn

Thus far on VanRamblings’ four-part series on homelessness + housing, we’ve tracked the history of homelessness in B.C., from the 1930s forward until now.

We have touched on a modular housing model as a temporary “fix” for our current homeless crisis, and suggested that homelessness is a national issue of critical importance that requires the intervention of the federal government, working with the provinces, to address the ongoing issue of human misery on our streets.

In the interview with Premier-in-Waiting, David Eby, Stephen Quinn holds Mr. Eby’s feet to the fire, questioning him on the resolution to homelessness in our city and province. Mr. Eby is forthcoming about what he feels is necessary: build social housing, lots of it, transitioning our homeless / barely housed population out of sub-standard, one room single occupancy resident accommodation, or temporary shelters, into livable, one-bedroom furnished apartments — with a bed, kitchen, bathroom and living room, TV, internet and all the amenities — this housing to be located in every neighbourhood across our city, what yesterday we referred to yesterday as the “Finnish model” in Wednesday’s VanRamblings’ column.

On the day VanRamblings attended David Eby’s campaign launch to become British Columbia’s 37th Premier, the event held at the Kitsilano Neighbourhood House —where Mr. Eby gave one of the best, most moving and humane political speeches we’ve ever heard — we wondered how Mr. Eby was going to position himself in order that he might retain power when the next B.C. election is called.

In 1996, BC New Democratic Pary leader Glen Clark positioned himself as a working man, a boy who grew up on the east side of Vancouver, who had fought all his life for better for all of us. A working class hero. Mr. Eby, whose father practiced law in Ontario as a partner in a prestigious law firm, and whose mother was a school principal could hardly pull off the Glen Clark’s “pulled myself up with my bootstraps” man of the people working class hero approach. What then for Mr. Eby?

“ICBC is dumpster fire.” “Money laundering in B.C. is artificially inflating housing prices.” “B.C. car insurance rates are too high … we’ll convert to no fault insurance, lower insurance rates, and provide a $400 rebate cheque to all B.C. motorists.”

David Eby, British Columbia’s Premier-in-Waiting Man of Action, ready to fix B.C. homelessness crisis

VanRamblings believes that British Columbia’s new “man of action” Premier, 45 years-young David Robert Patrick Eby will upon assuming the office of Premier of British Columbia declare a homelessness crisis emergency in our city and province.

220 Terminal Avenue, the first temporary modular housing building constructed on City-owned land

In declaring a homelessness crisis emergency Mr. Eby will, as a temporary measure, order the construction of 1500 units of modular housing, to be built on city and provincial Crown land with all possible haste, on suitable sites across Vancouver, those modular housing sites to be occupied no later than the autumn of 2023.

Premier Eby will then appoint a Commission with the mandate of reforming the multi-billion service model that allegedly provides succour to those resident on the DTES, “a broken system,” Mr. Eby has said, that ill serves those in need.

A tent encampment at Vancouver’s CRAB Park, which has maintained for two years. (Ben Nelms/CBC)

As a next order of business, VanRamblings believes that a Premier Eby will expedite the construction of social and affordable housing on city-owned (Vancouver is a creature of the provincial government), provincial Crown land, and in a co-operative agreement, on federally-owned Crown land, on a 66-or-99 year leasehold basis, ordering that the city of Vancouver will charge no development permit, or related fees, and that the approval process for construction of the social and affordable housing will occur sans City Hall red tape, and any measure of undue delay or intransigence on the part of the Planning, Urban Design and Development Services Department, lest the office of the Premier assume full responsibility for every aspect of the approval and construction of this necessary new housing.