Each and every year for the past two decades, and more, hundreds of new homeless persons arrive on our shores to call Vancouver their new home.

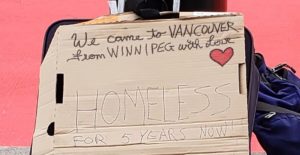

These homeless persons, arriving without any money or resources, come down to Vancouver from the north of our province, from the Okanagan, Vancouver Island or some other provincial locale. More of the newly arrived homeless make their way to Vancouver from the Prairies, Ontario, Québec or the Maritimes, more often than not having been provided with a bus / train or plane ticket furnished by their provincial social services Ministry, having been told, “Go west, where the skies are blue, the weather warm, the people friendly, and the streets are paved with gold.”

A surprisingly large contingent of Vancouver’s new homeless arriving in our city each year, somehow make their way across the U.S. borders to both the north and south, arriving (mostly) from California — but, as well, from a polygot collection of other U.S. states — as well as from Mexico, and Central and South America.

Then, there are Vietnamese, Thai, Indonesian or Filipino citizens who jump ship (or who were onboard for the long journey across the Pacific, as stowaways) to arrive in Vancouver, here to stay, they hope, here to make Vancouver their new home.

Upon arrival, these émigrés to our lustrous Pacific shores often make contact with one of the hundred or more outreach workers populating the downtown eastside, those angels of mercy helping the newly arrived find a place to stay, registering them for social assistance, or persons with disability coverage, making sure that they’re covered by B.C. Medical, ensuring their needs are otherwise looked after.

Then, among the newly arrived émigrés, there is the contingent who want to stay under the radar: the heavily drug dependent, and the drug dealers.

Apart from Vancouver’s (mostly) good weather, the other key reason this new homeless population moves to Vancouver relates to the ready availability of drugs. Vancouver is North America’s largest drug distribution centre. Heroin arriving from Afghanistan through Amsterdam will find its way to Vancouver, to be carried across the continent. The raw ingredients to make fentanyl arrives in Vancouver from China (the Canadian government long ago staunched the supply of raw fentanyl into Vancouver … now fentanyl has to be “mixed”, locally, in Vancouver).

Of the new arrivals each year, approximately one-third of the new “out of town” homeless population remain in Vancouver, many sleeping in doorwells, under park benches, in alley ways, in garages, loading bays, under bridges, in and around Jericho or Stanley Parks, or have found themselves shelter, or life in an SRO.

Many others make their way to municipalities across the Metro Vancouver region, mostly to Surrey and Burnaby, but as well to the Tri-Cities (Coquitlam, Port Moody and Port Coquitlam), Ladner, Langley and Richmond, Haney, Maple Ridge and Pitt Meadows, not to mention the North Shore.

A contingent of members of the Vancouver homeless population make their way into the Fraser Valley (as far out as Chilliwack, Agassiz and Hope) or over to Vancouver Island — mostly Victoria, Nanaimo and Duncan, but across the entire Island, as a whole — with a sizeable number heading to the Okanagan’s inviting climes.

A remaining number of homeless persons return home — with the provincial government, more often than not providing the fare home — having enjoyed (or not) their brief vacation on the west, with a smaller number deported or in jail.

All of the above is by way of saying, when the annual Homeless Count is conducted each March, the number of homeless persons always rises, sometimes by substantial numbers, and not because it’s persons — seniors, or others — who have found themselves evicted from their apartments because rents have become too high, or young people who have aged out of the care system (or lack thereof) provided by the province of British Columbia.

Rather, this is a sorry tale of human misery.

In some sense, then, the problem of resolving Vancouver’s homelessness crisis would seem irresolvable — the more housing that is built, the more modular housing structures constructed, the more hotels purchased by the province, the more SROs that are renovated by the province to make this kind of congregate housing livable, the more shelters that are made available, the more homeless persons who will arrive on our shores, this year, and all the years beyond.

Today’s VanRamblings’ column is not prescriptive, nor do we attempt to provide historical context — we’ll do that later in the week, plus offer what we feel may be a short term fix to help alleviate the lives of human misery for persons who are living at a bare subsistence level, as VanRamblings sets about to present an historical context dating back decades, through until today.