The age of grievance and the culture of complaint have become defining features of contemporary political discourse in Canada and beyond.

In Frank Bruni’s The Age of Grievance, the New York Times’ Opinion columnist and Duke University professor, outlines how political figures have weaponized grievances to galvanize support, shift public sentiment, and redirect anger into votes.

This culture of dissatisfaction, cynicism, and victimhood has seeped into the Canadian political landscape, informing the strategies of major conservative figures, including Pierre Poilievre, the leader of the Conservative Party of Canada, and John Rustad, leader of the Conservative Party of British Columbia.

Understanding how this age of grievance shapes political campaigns is crucial to grasping the shifting nature of voter behaviour, particularly as it pertains to the rise of far-right or populist sentiments.

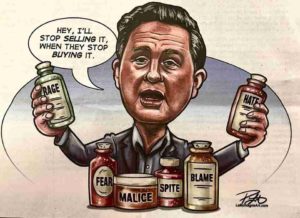

Pierre Poilievre and the Politics of Grievance

Poilievre has skillfully harnessed the culture of grievance as a key political strategy.

At the heart of Poilievre’s appeal is his ability to frame issues as part of a broader narrative where everyday Canadians have been wronged by government elites, bureaucrats, or a distant political class. By positioning himself as the voice of “common sense,” he taps into frustrations felt by many Canadians — whether it’s over affordability, housing, inflation, or perceived loss of personal freedoms.

Bruni’s The Age of Grievance highlights how figures like Poilievre manipulate these sentiments to create a sense of urgency.

Poilievre frequently paints a picture of a country under siege by wokeism, government overreach, and inflationary policies. He taps into a sense of national victimhood, where Canadian values and identity are under attack, positioning himself as the solution to restore these lost values. This isn’t merely a campaign tactic, but a broader effort to reshape Canadian political consciousness.

Bruni notes that “in a grievance-fueled culture, anger becomes the rallying cry, and solutions are often secondary to the preservation of outrage.”

This applies perfectly to Poilievre’s style.

His criticism of Prime Minister Justin Trudeau’s handling of the economy, energy policy, and pandemic restrictions follows a pattern of inflaming grievances rather than offering concrete, nuanced solutions. In doing so, Poilievre consolidates support not by offering optimism, but by fanning the flames of dissatisfaction.

British Columbia and the Politics of Complaint

In British Columbia, the age of grievance has similarly found fertile ground.

The current provincial election has become a battleground for competing narratives of grievance, with John Rustad of the BC Conservative Party emerging as a central figure exploiting this atmosphere for political gain.

British Columbia, a province often associated with progressive politics, has seen increasing polarization. The polarization between the BC New Democratic Party (NDP), which has governed for years, and rising conservative forces, such as Rustad’s BC Conservatives, reflects the influence of a growing culture of dissatisfaction. Voter frustration over affordability, housing crises, healthcare shortages, and environmental policies has coalesced into a broader sense of disillusionment with the political establishment.

Rustad’s campaign has capitalized on this sense of grievance, positioning his party as the “real alternative” to the governing NDP.

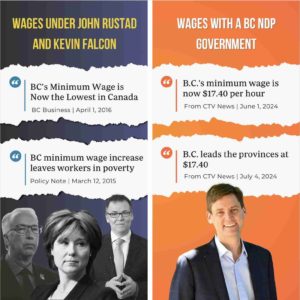

John Rustad is not new to politics, he is a career politician with a 20-year record of costing you more.

That’s a risk you can’t afford. pic.twitter.com/6eqDaPZEao

— BC NDP (@bcndp) September 5, 2024

Rustad frames the government as “out-of-touch elites” who care more about woke policies, such as climate action, than about the daily struggles of British Columbians. In echoing Poilievre’s national campaign strategy, Rustad paints a picture of a province where citizens have been ignored and betrayed by the government. By presenting himself as the antidote to this betrayal, he has tapped into a well of voter dissatisfaction.

As Bruni notes, “leaders who exploit grievances do not seek resolution, but rather fuel the perception of perpetual crisis, ensuring that discontent becomes a permanent political currency.” Rustad’s campaign exemplifies this. He doesn’t offer a transformative vision for British Columbia but rather sustains a sense of crisis — over taxes, land use, or environmental regulations — that keeps grievances alive.

The Grievance Mindset and Populist Shift

The age of grievance has had a marked impact on voter behaviour, not only in British Columbia but across North America.

Many voters who feel alienated or left behind by the status quo are drawn to conservative or even far-right parties that exploit their frustrations. This is evident in how Rustad’s party, much like Poilievre’s federal campaign, attracts voters by offering simple answers to complex problems, such as opposing carbon taxes or claiming that crime and drug use are rampant due to “soft-on-crime” policies.

Bruni warns that in such a grievance-driven environment, “voters can be seduced by voices that promise a return to simpler times, even when those promises are illusory.” This has been true for British Columbia voters who, dissatisfied with the NDP’s handling of the housing crisis or healthcare system, may turn toward a party that doesn’t represent their best interests but resonates with their frustrations.

The age of grievance thus contributes to a political atmosphere where voters are more likely to make choices based on anger or cynicism rather than long-term policy benefits. This phenomenon explains why populist and even far-right movements, which exploit dissatisfaction but offer few concrete solutions, have gained traction even among voters who might otherwise support progressive policies.

David Eby and the Progressive Response

For David Eby and the British Columbia New Democratic Party, the challenge is how to counter this grievance-fueled narrative.

The key may lie in offering a vision of hope and forward-thinking solutions, rather than merely responding to grievances with defensive rhetoric. As Bruni suggests, “the antidote to grievance is not more grievance, but a reassertion of optimism and constructive action.”

Eby’s task is to convince voters that their frustrations — though real — are best addressed through thoughtful governance, rather than reactionary policies.

By focusing on housing, healthcare, and climate action, David Eby can remind voters that while grievances may persist, real solutions require sustained effort and collaboration. Moreover, Eby must highlight the dangers of grievance politics, pointing out that figures like Rustad are more interested in sustaining voter anger than in solving the province’s problems.

The age of grievance has become a dominant force in both federal and provincial politics in Canada. Conservative leaders like Pierre Poilievre and John Rustad have capitalized on this culture to galvanize support, while progressive parties like the B.C. New Democrats must find ways to navigate this political landscape without succumbing to the cynicism that defines it.

By offering solutions that go beyond complaint, leaders like David Eby can potentially counter the divisive forces that have emerged in this era of grievance-driven politics, and form government post Election Day, on Saturday, October 19th.