Vancouver’s West End in the 1960s, a comfortable family neighbourhood next to Stanley Park

In the 1960s, when Vancouver was still very much a village rather than the thriving metropolis we know it to be today, in those near soporific, pre-movement times, rare was the occasion when the citizens of our fine city got up on their hind legs to protest the status quo or what seemed like the inevitable, as wealthy old men of circumstance wrought change unchallenged, untrammelled by reflection.

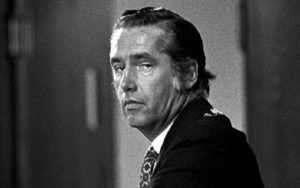

Tom ‘Not So Terrific’ Campbell, controversial Vancouver Mayor, in office from 1966 to 1972

Such was the case in 1971, when Vancouver Mayor Tom Campbell and his Non-Partisan Association Council cohorts decided that the time had come to develop the Coal Harbour site at the entrance to Stanley Park, cherished green space of long duration, but not much longer if Mr. Campbell — and the provincial government, led by 17-years-in-power Socred Premier W.A.C. Bennett — had their way.

The Coal Harbour site, owned by Harbour Park Developments, a politically connected local group with strong ties to the Non-Partisan Association, developer Tom Campbell — who in 1966 ran for Mayor as an independent, and won — and the Socred government, first unveiled their development plans in 1965.

The Four Seasons Hotel chain came forward in 1965 with a $40-million development plan on the Coal Harbour waterfront. The initial plan would house 3,000 people in three 30-storey buildings, including a 13-storey hotel and townhouses.

Over time, the development plan was expanded into an unheard of at the time $55-million massive multi-tower plan, with 15 apartment towers, ranging from 15 to 31 storeys set to be constructed on the then green space, a veritable high-rise forest along the Georgia Street causeway entrance to Stanley Park.

As you might well expect, the massive tower development plan for the 14-acre Coal Harbour waterfront site turned into a contentious issue that lasted for years and years, causing increasing numbers of people to rise up in adversarial opposition. The public wanted the site preserved as green space. Developers, Tom Campbell, the Non-Partisan Association, and the Social Credit government had other ideas.

Each week, for years, the community rose up in high dudgeon.

After all, the West End at the time was a single family dwelling neighbourhood, the tallest structure in Vancouver was the Marine Building on Burrard Street.

In 1966, each weekend for the first couple of months, a rag tag group of community activists — who came to include a young storefront lawyer, Mike Harcourt, and Darlene Marzari, an employee of the City — protested on the deserted site. Over time, their numbers grew to five hundred, and then a thousand, rising up in protest and stark and strident opposition to development plans for the cherished green space.

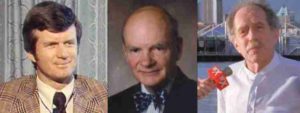

Vancouver City Councillor and then Mayor, Art Phillips; Councillors Walter Hardwick and Harry Rankin

In 1968, a reform-minded Art Phillips and his friend, Walter Hardwick — an Urban Planning professor at UBC, and a community leader whose work would come to shape the city and Metro Vancouver region — ran for Vancouver City Council under the banner of a civic party they had created, The Electors’ Action Movement (TEAM), securing two seats on City Council, joining a young lawyer by the name of Harry Rankin, who had been elected to Council in 1966, sitting in sole opposition to the developer-friendly Non-Partisan Association City Council of the day.

Throughout their campaign for office in 1968, both Art Phillips and Dr. Hardwick stated their clear opposition to the Harbour Parks Development / Four Seasons plan for the green space at the entrance to Stanley Park, standing with the community, and with Vancouver City Councillor Harry Rankin. Would community opposition to the Coal Harbour development plan, in ever increasing numbers, carry the day?

Only the continued opposition of Vancouver citizens could and would tell the tale.

A model of the Harbour Park Developments proposal for the entrance to Stanley Park. The $55-million development would have constructed 15 high-rise towers. Photo: Selwyn Pullan / PostMedia

By the early spring of 1971, hundreds of community activists gathered each weekend on the Coal Harbour site at the entrance to Stanley Park, in protest.

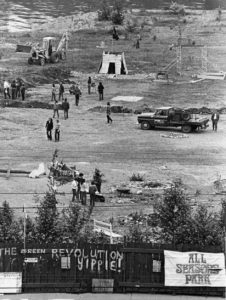

June 7, 1971. All Seasons Park after squatters reclaimed the site. Photo credit: Vancouver Sun

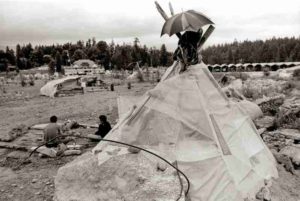

On May 29th, 1971, seventy community activists (hippies they were called by the press) took matters into their own hands, ripping down a fence surrounding the site, storming onto the Coal Harbour waterfront site to plant maple trees, setting up a camp of tents and ramshackle huts, the protest squat sustaining for a year, each subsequent weekend joined by hundreds and hundreds of concerned, mostly young, Vancouver citizens, at what was now called All Seasons Park.

September 23, 1971. An A-frame squatter’s shack in All Seasons Park. Photo: Ross Kenward / PostMedia

In early 1972, bowing to public pressure, a combative Tom Campbell announced there would be a plebiscite on the Four Seasons development, but that only property owners could vote.

This was roundly denounced at a public meeting on June 21, when urban planner Setty Pendakur dubbed the project “the biggest abortion in the history of development in Canada.” Pendakur said the development would create traffic chaos at the entrance to Stanley Park, that Council was confusing people with its plebiscite.

Property owners voted to reject the Four Seasons proposal by 51%. Then the federal government stepped in. On February 10, 1972, Pierre Elliot Trudeau’s government killed the proposal by withholding the transfer of a crucial water lot.

1972. Alderman Harry Rankin talking to activists at All Seasons Park. Photo: Gord Croucher / PostMedia

With a new Mayor and majority progressive T.E.A.M. (The Electors’ Action Movement) Council voted into office in 1972 by a public eager for change, led by Mayor Art Phillips, with Walter Hardwick, Darlene Marzari, Mike Harcourt and Setty Pendakur securing seats on, perhaps, Vancouver’s most progressive Council ever, in November 1973, the City of Vancouver bought the entire site for $6.4 million.

The green space at the entrance to Stanley Park is now known as Devonian Harbour Park, but for some of us, it will always be All Seasons Park.

Some historical source material for this article provided by Vancouver Sun reporter John Mackie.

There is a correlation to be drawn between the movement leading to the defeat years ago of the Harbour Park Development project at the entrance to Stanley Park — championed by the City Council of the day — and the movement opposition of, now, 200 informed citizens (and more) who gathered at City Hall two weeks ago, and again this past Monday evening to state their opposition to the initiative of the Ken Sim-led ABC Vancouver City Council to eliminate Vancouver’s cherished, 135-year-old, independent and elected Board of Parks and Recreation.

Movements start off small, with generally only a few of our better informed citizens coming to the fore to state their opposition.

As time passes, more of our citizens become informed, inform themselves, taking the power to change for the better into their own hands, to rise up for the better, to work in common cause with friends and neighbours who share their concern to, in time, elect a more democratically-minded local government committed to the livability of our beloved city.