My aunt Freda was a vagabond, but a vagabond who typed at 80 words a minute, and took shorthand at up to 120 words a minute — her stenographic skills much in demand across all of Canada, for many many years.

For 50 years, my aunt traveled the country — there was no city or medium-sized town where she didn’t work, and given her skill set, jobs were easy to come by, references at the ready from previous employers.

My aunt would work two or three jobs a year for two to three months each time — in St. John’s Newfoundland (the only place she ever worked twice), Regina, Edmonton, Hamilton, Windsor, Saskatoon, Halifax and Victoria.

My aunt Freda would write to me from these far flung places across Canada where she’d taken employment, promising always to return in “just a few weeks.”

Vancouver’s crown jewel, the 1000 acre Stanley Park, the photo above taken in 1958

Throughout my young life, my primary caregiver was my aunt Freda.

Given that my mother, almost throughout the entirety of my life, worked three jobs at the same time, 16 hour days six days a week and a 24-hour day on the seventh day, I rarely saw her, she simply wasn’t a presence in my life or in my home, with the exception of summer, when we — my sister, my mother and I — would travel for a two-week vacation to wherever my aunt was located.

During the first 10 years of my life, my Aunt Freda cared for my sister and I, fed us, bathed us, took us to Stanley Park in the years we lived in Vancouver, took us on summer vacations, made sure that we enjoyed ourselves, and would learn about the world during the days, weeks and months that she cared for us, and otherwise provide love for the both of us.

Generally, my aunt would stay in our family home three times a year, sometimes more, for an average of six weeks on each visit.

In fact, my Aunt Freda was the only person who ever told my sister and I that she loved us. My father didn’t do that or even hint at it, love seeming to be a word not in his vocabulary, and most certainly my mother never told my sister and I that she loved us — although I think she showed it in many ways — and neither did anyone other than my Aunt Freda.

Aunt Freda was, for all intents and purposes, my mother — that’s the role she chose to play.

I was her favourite — any depth of insight into life, I gained from her.

Our conversations lasted hours — she wanted to introduce me to the world, to make me aware of my environment, to help me to see that I was part of a human collective of those who lived around me, and as the years went by, farther afield, as she helped me to see that I was part of the world community.

In the summer months, as I write above, my mother, sister and I would travel to whichever western Canadian city she was working in — in the summer, she always took employment in an easily accessible by rail western Canadian city .

My mother, sister and I would stay with her in her small, one-room “apartment” (more like a tiny hovel, but still), in order that we might attend Klondike Days in Edmonton, or the Calgary Stampede, or the Red River Exhibition in Winnipeg, or whichever town had a fair that summer that my aunt felt was recommendable and worthy of my family — always sans my father — visiting and staying with her, always enjoying our truncated time together.

Of course, part and parcel of that was the train ride to and from whichever western Canadian city we were visiting, but that’s a story for another day.

When my family — including my father — moved to Edmonton in the summer of 1959, I spent the month of July in High River, Alberta staying with my grandfather on his massive family farm, and much of August in Lethbridge with my aunt Anne, uncle Dave and their children, my cousins, before moving into the rental home my parents had found for us in Edmonton, where I began Grade 4 in September 1959 — a fortuitous circumstance that would change my life.

In the late 1950s, Alberta had legislated an academic programme of excellence for students into which I was enrolled. In British Columbia, the province had adopted two educational streams: academic and vocational.

If you happened to live in a working class area of Vancouver, you were almost automatically streamed into the vocational programme.

When I returned to Vancouver for Grade 7, in the late summer of 1962, as I had been enrolled, and done well in Alberta’s Enterprise Programme of Excellence — as it was called at the time — upon my return to Vancouver to attend Templeton Secondary school, of all my friends with whom I had attended Grades One through Three, I was the only child / student who now found himself enrolled in the academic programme at Templeton.

I recall at the graduation ceremony in 1968, how disappointed many students were to find that graduating in the vocational programme did not make them eligible for entry into college or university, that they’d have to start all over again.

Rank class discrimination, that’s what it was plain and simple — kids came from poor families, and they’d become the “worker bees” as we were so often told while attending Templeton Secondary.

Two stories about my aunt, both of which are Edmonton-based.

Borden Park, in northwest Edmonton, at 148 acres one of the city’s largest parks

In the summer of 1960, after my family had moved to north Edmonton from the inner city, on my August 11th birthday that year, my parents had taken my sister and I down to play at Borden Park, in northwest Edmonton, not too far from where we lived, a massive green space in that area of the city, sometimes used as fairgrounds, with a community centre, tennis courts, a pool, and two outdoor pools, one for younger children, another for teenagers and adults.

The day was sunny and bright, the sky a deeper and richer blue that I can ever recall having seen prior to that date.

As it happened that year, my aunt Freda had not come to stay with us during the first seven months of the year — her services were required in St. John’s, as she found herself working on an inter-governmental project of some great import to both the province and the federal government. Of course my aunt wrote to me frequently, but beautifully handwritten letters aside, I missed the dickens out of her, and in my letters to her, I begged her to come and stay with us in Edmonton.

But it was not to be, for all the reasons she explained in her correspondences.

While playing on the park’s roundabout, along with a number of other children pushing the roundabout to go faster, despite the hot sun beating down from above, I felt a chill run through my body, a pang that was so chilling as it shot through my veins that I alighted from the roundabout, and moved away onto a quieter green space nearby, just standing there shivering, for a moment wondering what was happening to me.

Turning away from the screaming children on the roundabout I began, alone, to walk north, away from my sister. Neither my younger sister Linda nor I had seen my parents in awhile, who’d told us they had some business to attend to, that we’d be fine in their absence, and I was to take care of my sister Linda.

I continued to move north along the green grasses, at first slowly, hesitatingly, when looking off into the far distance, I saw three figures walking closely together, indefinable figures, the sun obscuring my vision, the distant figures almost apparitions, as another pang of cold shot through my body, at which point I began to run, to run faster in the direction of the three apparitions than I had ever run in my life, because I knew who the middle person of the three was, even if I could not properly see who it was.

And I began to cry, running across the green field sobbing, running as fast as I could in the northerly direction of the three figures who I could not quite make out, but I knew were my parents and my aunt, and I ran and ran and ran, tears now gushing down my cheeks on that 10th birthday summer’s afternoon in August of 1960, on a day I will never ever forget.

And when I was upon my parents and my aunt, I jumped into my aunt’s arms, wrapping myself around her, my head on her right shoulder, the two of us holding each other as tightly and closely as we could, both of us now crying, my parents standing back in wonderment, their faces lit up smiling.

Placing me back on my feet, my aunt looked at me and said, “Raymond, I have arrived in Edmonton just this day, only an hour or so ago, so that I could be here for your birthday, to take you and your parents and Linda to dinner tonight. And I have presents for you, as well, which I will give you when we return to your home, and before we go to dinner tonight.”

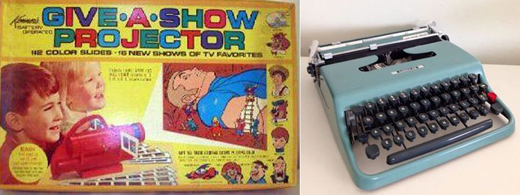

The presents? There were two, as promised: an Underwood typewriter that would allow me to type ever longer letters to my aunt as she found herself in some far flung location in Canada — with the facility to type easily and well, a salutary talent and much-used skill I employ to this day — the second present, a toy 8mm movie projector that both reinforced my love for film, and a device that would bring me much joy in the months to come.

Running across that green field in Borden Park on the day of my 10th birthday resides in me still as a much cherished event in my young life, making me aware, if I was not already, that there are more than three dimensions in our existence — because I knew that my aunt was in the park minutes before I saw her and ran into her arms, when she told me she loved me, as I knew she did, and as I loved her.

My aunt stayed with my family to the beginning of my Grade 5 school year at Eastglen Elementary School, after which she was off again, this time to Saskatoon, where she worked through until February, when she returned to Edmonton for three weeks, then after traveling back to Saskatoon, where my mother, sister and I would spend the better part of July 1961 with her.

In the winter of 1962, my aunt made one of her now more infrequent visits to stay with my family, my mother working three jobs still, my father working at the Post Office, my sister and I alone at night.

One near frozen mid-winter February evening, after making and serving dinner to my sister and I, a dinner almost needless to say in which a delicious salad was featured prominently in the dinner — having arranged with a neighbour for babysitting for my sister, my aunt asked me if I’d like to go to see a film with her on the south side of Edmonton, near the University of Alberta campus.

Of course, I said yes.

That evening, I saw my first foreign film, my first Fellini film, and a film that would go on to win the Best Foreign Language Film Academy Award late the very next month: La Dolce Vita, a film I fell in love with, as did my aunt, a film my aunt and I talked about all the way home on the bus, a film that began my life long love affair with sensuous European women onscreen, with foreign language & world cinema.

In all the years of my young life there was love in my life only when my aunt Freda would arrive to stay with us in our home. Not until I met Cathy in late 1969 did I feel love from anyone other than my beloved aunt Freda.

My aunt remained a fixture in my life through all the years of my attendance at university and throughout the years of my marriage, my aunt Freda the woman I look upon as my “real” mother, the mother who loved me, and cared for me, who knew me better than any other person in this world, and the person — along with each of my two children — I will always love most.