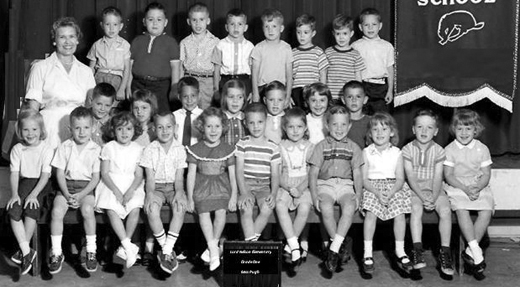

Lord Nelson Elementary School, on Vancouver’s eastside, where I attended Grades 1 thru 3.

The summer of 1959, after I’d completed Grade 3 at Lord Nelson School in Vancouver, in August of ’59, my parents moved from Vancouver to Edmonton to be closer to family — on both my mother’s and father’s sides of the family.

In Alberta at the time, the provincial government had adopted what they called an “Enterprise Programme,” a focused academic programme meant to engage students intellectually while providing them with the tools they would require to compete successfully at post-secondary university.

While all other Canadian provinces had adopted a two stream programme, one academic (university bound), the other vocational (meant to prepare students to work in the trades), Alberta was having none of that — educational achievement at the highest possible level was Alberta’s goal, the curriculum requirements rigorous, demanding and challenging, and consistently above grade level.

The Enterprise Programme was defined by competition and the striving to become the best possible student — failure was never an option, doing your best was expected and required, academically and socially.

Future leaders were being trained in Alberta.

“The provincial government meant to produce the best and the brightest, informed by a progressive educational ideology that Alberta was the first Canadian province to adopt in the 1950s, an educational philosophy that was child-centred, subject-integrated, with an activity-based approach, known in Alberta as the Enterprise Programme, focused on content centered courses in History, Geography, and Civics integrated into a new course: Social Studies, which was taught across all grade levels, this new subject emphasizing the development of democratic, co-operative behaviour, and inquisitiveness through experiential learning.”

Lynn Speer Lemisko & Kurt W. Clausen, Connections, Contrarities and Convolutions: Curriculum & Pedagogic Reform in Alberta; Faculty of Education, SFU, March, 2017

In the summer of 1962, my parents made the decision to return to Vancouver — the reasons unclear to me, but whatever the case, in the summer of ’62, living at 2136 Venables Street, I was enrolled at Templeton Secondary School, then the toughest school in Vancouver (that mantle would soon be claimed by VanTech — but in 1962, Templeton was the school where all the toughest “juvenile delinquents” were enrolled, although truth to tell, many of those students found themselves behind lock and key at the Brannen Lake Juvenile Correctional Facility).

From Grades 7 through Grade 12, I attended Templeton Secondary School.

Based on my experience in Alberta, I was enrolled in the academic programme at Templeton, whereas every person I’d attended Grades 1 thru 3 with at Lord Nelson found themselves enrolled in the vocational stream.

Odd, I thought to myself at the time.

Another odd thing I found: from the spring of 1963 on, my grades never soared about a C-average — whereas in Alberta, I’d been a straight A student.

Unlike most other students enrolled in the academic programme, I was required to take vocational classes — and from Grade 8, I was enrolled in typing and secretarial classes, unlike any other student in the academic stream.

Although a typing speed of 160wpm would serve me well later in life, I still found it odd, and just a bit concerning, that I was required to take three clerical classes each year through to graduation.

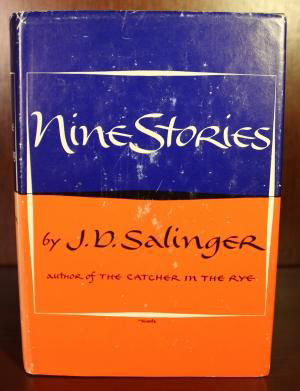

From Grade 8 on, I was also concerned that when I submitted an essay in Social Studies or one of my English classes, it either came back to me with a C, a D or a fail — with a comment from my teacher that someone other than me had written the essay, or I had either plagiarized or copied directly the work of someone else.

By the time I reached Grade 12, where I had achieved an A- average in French, was taking the lead in the school plays, and editing the student newspaper, I was disappointed to receive a D in English, and a fail in History and Geography.

I recall one spring afternoon in 1968, the teacher having turned down the lights, with soft music playing in the background, the teacher asking the students in my Grade 12 English class to write a stream of consciousness essay, which I was only too happy to do.

When I submitted the essay to the teacher, she took a glance at the essay and tore it up, saying to me, “You didn’t write this. You either copied it from someone else or had the essay prepared in advance (note. there had been no notice of a stream of consciousness essay taking place in class that day). You receive a fail for the essay. I’m disgusted with you.”

A dozen years later, I was the Assistant Director of Teacher Training, PDP 401-402 at Simon Fraser University (a position I held while working on my Master’s degree).

The English teacher referred to above had taken a seconded position as a PDP Faculty Associate — in essence I was her boss.

When we first connected, in September, at the outset of the 1980 academic school year, almost the first words out of her mouth were, “I had a student with your name at Templeton Secondary. How odd that you should both have the same name,” at which point I informed her that the Raymond Tomlin she had taught, and the person standing in front of her was one and the same person. She looked aghast, stammering, “But how?”

I told her I had a 3.8 grade point average and two undergraduate degrees, and was currently enrolled in a Master’s programme at the university, letting her in on what I am about to write and record for posterity now …

In June of 1968, when I was about to graduate, as was the case with all of the other graduating students, I met with Ken Waites, the patrician, white-haired Principal at Templeton Secondary School, in his office with the door closed, and this is what he said to me …

“Well, Raymond, even though you’re a couple of courses short of graduation, given your failing grades in History and Geography, I am nonetheless going to graduate you anyway — because any kind of academic future is clearly not in the cards for you. I want to tell you something that we’ve kept from you for the past five years: for each of those years, you were recorded as having the lowest IQ of any student enrolled in the Vancouver school district, not just at Templeton, but city wide. Your teachers and I had often wondered, given your low IQ, how it is that you locomoted yourself from point A to point B. Someone with as low an IQ as you shouldn’t even be able to speak — but here you are.

You’ve probably wondered to yourself, why you were required to take three clerical courses each of the past five years. The answer is easy: you spell well, and it was clear early on that you had an aptitude for secretarial work, your typing speed and accuracy superior. Your guidance counsellor and I determined a long time ago that the best course in life for you would be to enter the clerical field, to be a secretary — because, clearly, you are possessed of no academic skill whatsoever, although you seem to have done well in French.

I have had these meetings with all graduating students, providing what I believe to be sound advice on how each student should proceed with his life following graduation. In your case, your best — and I would say, your only — hope is as a secretary. Thank you for meeting with me this afternoon, Raymond. All the best in your future.”

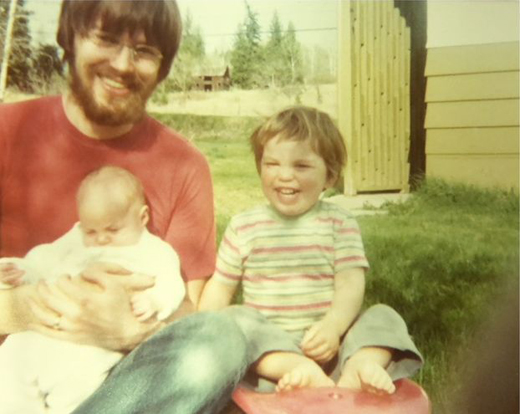

In 1970, my new wife insisted I enroll at Simon Fraser University, where students with an inferior academic record were being accepted, in order to build the student body.

In my first semester at SFU, I achieved 3 C’s and two B’s. In my second semester, 3 B’s and 2 A’s — and every semester after that, straight A’s (not that I ever cared about grades, as did many of my fellow students — I was just hungry for knowledge, and curious about the world, eager to learn as much as I could, at one point early on not leaving SFU’s Burnaby campus over an 18-month period).

I loved to read, I loved to write, I loved to learn, I was curious about everything — being at Simon Fraser University and hanging out with and being challenged by the best and the brightest was like a dream come true for me.

My curiosity about life, about all aspects of our existence on Earth remains to this day — I want to read all of the papers of record every day (and I do!), to engage with nation builders and city builders, to work with persons of conscience, to work towards better, fairer, more just.

And I am afforded that opportunity each and every day, surrounded (outside of my plangent housing co-op life) by strong-willed persons of conscience who mean to build a better and more just world. As such, my life is near filled with joy!