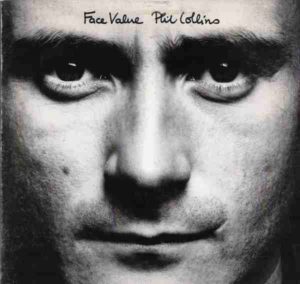

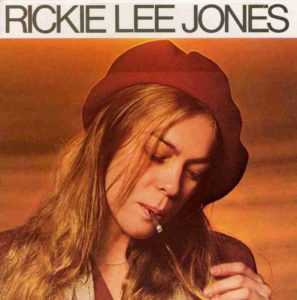

With the lights down in the Orpheum Theatre, all you heard for the first 20 minutes of the Rickie Lee Jones concert in 1979, in support of her eponymous début album, was the street-wise, near angelic voice of Rickie Lee Jones as it filled the venue, investing itself deep within the souls of the thousands who had gathered to see and hear the performer they had come to love, and love through and up until this day.

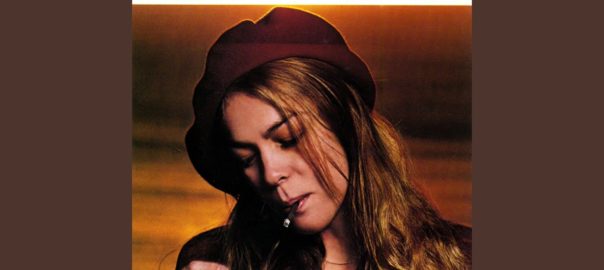

Rickie Lee Jones in New York City, 1979

A fractured childhood, years as a hippie drifter, her incredible adventures before she found fame — and of her intense relationship with Tom Waits in the 1970s — fill her life story.

Rickie Lee Jones was just three years old when she made her début as a performer, appearing briefly as a snowflake in a ballet recital of Bambi.

“I heard the audience’s applause and took it personally,” she writes in Last Chance Texaco, a vivid memoir that traces the arc of her often turbulent life from unsettled childhood to uneasy fame. “I remained bowing long after the other snowflakes had melted and left the stage. The dance teacher had to escort me off, but the audience was delighted and the die was cast. I liked it up there.”

An outsider by temperament, Jones has long walked to her own slightly off-kilter rhythm.

This song catapulting Rickie Lee Jones—winner of the 1980 Best New Artist Grammy—into prominence

In 1979, when she gatecrashed the mainstream with her self-titled début album and the buoyant, jazz-tinged hit single, Chuck E’s in Love, her sudden celebrity left her feeling all at sea.

“That was the biggest test,” she says, “For someone who always felt on the outside to suddenly have everyone treat me like I was above them, that was really hard. It was difficult to know how to be a person when that was going on.”

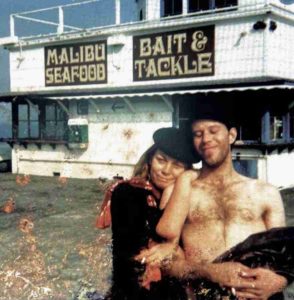

Back then, she was marketed as a boho songstress in a beret. A brief but intense relationship with Tom Waits, whose creative sensibility fleetingly chimed with her own, added to her cachet of cool. As a couple, they seemed to have emerged fully formed out of their own creative imaginations.

Rickie Lee Jones with Tom Waits, her partner at the time, on Santa Monica Pier, in the late 70s

If Waits’ stumblebum persona relied to a degree on creative method acting, she was the real deal: a survivor who had, as she puts it in the prologue of Last Chance Texaco, “lived volumes as a young girl long before I was famous”.

Now, aged 69, Rickie Lee Jones has finally settled in New Orleans, an easy-going, music-haunted city that suits her temperament.

“I’ve been here ten years, which is a kind of a record,” she says, laughing, in an interview she gave to The Guardian’s Sean O’Hagan. “I think it’s a good town for me. It’s still a bit weird. There’s lots of music and not so much celebrity. I guess I’ll stay here for a while if it doesn’t get washed away in the flood.”

Jones was born in 1954 in working-class Chicago, where her mother, Bettye, hailed from. Bettye was taken into care as a child and raised in state institutions after her father was jailed for stealing chickens. She added the “e” to the end of her first name on her release, aged 16, to symbolize a new beginning.

In Chicago, she met Richard Loris Jones, a struggling musician whose father was a vaudeville entertainer who went by the name of Frank “Peg Leg” Jones, his fame exacerbated by his violent streak. Survivors both, the couple moved from state to state during Rickie’s childhood.

“What were they running from? From cities, houses, and eventually, themselves, but they never got away from their difficult childhoods or their love for each other.”

For all its uncertainty, her childhood was often magical. When she was four, the family settled for a time in the ‘quiet town’ of Phoenix, Arizona, where she roamed freely in the desert, rode horses, and had adventures with her imaginary friends.

As a young girl, music was a conduit to another world of possibility. She saved up her pocket money to buy the soundtrack of West Side Story, whose street-opera dynamics would later find their way into her songs. When she sang songs from the album to herself as she played on the street, other children, and sometimes adults, would stop to listen.

“I drew a crowd! Music had built an accidental bridge between me and the world.”

A young Rickie in 1968: ‘I spent most of my life in cars, vans, and buses.’

Jones has described her own teenage adventuring as “a little bit Oz, a little bit Huck Finn”. That barely does it justice.

Aged 14, she lived in a cave as part of a commune, hitchhiked on her own from Big Sur to Detroit when not much older, and risked a lifetime in jail driving to Mexico and back with hippie outlaw dope smugglers.

“How could I have done all those things? But I did. Kids are wily.”

Nevertheless, there were times when she sailed too close to the wind, winding up in jail more than once, usually on suspicion of being an underage runaway with a false ID — which she was. On the Canadian border, she was arrested for “being in danger of leading a lewd and lascivious life” — she was braless under her T-shirt. She recalls several tearful calls to her parents, who, more often than not, travelled vast distances to take her home.

While living in Mexico with a boyfriend, she was abducted by a rogue cab driver who drove her into the jungle intending to rape and possibly kill her. She was saved by the sudden appearance of a bus load of Federales.

“There were some bad things that cast a long shadow.” she says. “They seemed to have living darkness about them that made me feel really frightened all over again.”

Jones eventually gravitated to Venice Beach in California, working menial jobs and singing in local bands to pay the rent. It was there in 1976 she began writing her own songs, the likes of Easy Money and Weasel and the White Boys Cool, peopling them with characters based on the maverick souls she had met along the way.

Jones first encountered Waits at the Troubadour in Los Angeles in 1977, where he watched from the shadows as she sang a handful of songs to a near-empty club. Soon afterwards, they had a one-night stand that ended abruptly with Waits cold-shouldering her the following morning.

“I was still standing on the step when he closed the door and walked away. The sun was up and it was already too hot. I was wearing high heels. I wanted to hide in a bush. I may have hidden in a bush.”

A few months later, she signed to Warner Brothers and “things started warming up again with Tom Waits”. Their romance was all-consuming.

“We fed a craving so sharp that we wanted to become each other.”

The romance lasted barely a year, and his departure left her devastated just as her sudden celebrity swept her along in its tidal sway. In his absence, she drifted into the orbit of other wayward creative mavericks, including the supremely gifted songwriter and guitarist Lowell George, lead singer of Little Feat.

“It’s hard to say what he was really like, because I never knew him when he was not on cocaine. He was out there all night long taking drugs. He didn’t seem to be making any head road into hanging around.”

A year after they met, George collapsed and died of a heart attack, aged 34.

There’s a reason people get addicted to heroin. There is something they like, some kind of solace, some kind of numbing

For a time, too, she became friends with the talismanic Mac Rebennack, AKA Dr John, whom she refers to as “a dubious character in my life; a creator and a destroyer”. In his company, she began using heroin, which she had tried just once before as a young hippie drifter.

“It’s not good to blame everything on my relationship with love,” Jones writes in her biography, “but, when I was younger, love was everything to me. I didn’t really have a self to hold on to when things turned bad. So, back then if a boyfriend said, ‘I don’t love you any more,’ I might go hurt myself. I wouldn’t try to kill myself, but I might go take drugs.”

“I think that we construct our personalities out of our family environment and mine was pretty unsettled. I was very loved, but that was probably the only healthy thing going on, but it’s possible that was not enough to keep me from being curious about the bad things in life, the forbidden things.”

Rickie Lee Jones, aged 69, living a quiet life in New Orleans, when not on a concert tour.

In the late 1970s, when car mechanics was a dirtier, oilier, greasier business, Jones’s eponymous début album of a singer-songwriter featured a jazzy, bluesey, heartfelt song about a truck stop that contained a multitude of references to the timing being wrong, dead batteries, disconnected plugs and cables, and looking under the hood to see what the trouble was.

Here was a woman who had hit on a metaphor for the heart as a malfunctioning piece of metal that could still be rescued in the right hands.

The mournful, elegiac song is strummed at a slow, sighing pace: the last chance to refuel before you run out of gas for many, many miles. There are references to Standard, Mobil and Shell, as well as to the man with the star. At the end Jones transforms her voice into the desolate howl of a passing vehicle, first approaching and then receding into the great American landscape.

On this muscular yet vulnerable track, which concludes the first side of the album, she sounds like she has all the time in the world — or at least all night. And you find yourself thinking: maybe Waits will be just around the corner, bouncing along in his old 55, with the sun coming up.

With her expressive soprano voice employing sudden alterations of volume and force, and her lyrical focus on Los Angeles street life, on Rickie Lee Jones’ self-titled début album she comes on like the love child of Laura Nyro and Tom Waits.

Given the population of colourful characters who populate her songs, she also might have had Bruce Springsteen in her bloodline (that is, the Springsteen of his first two albums) — although the prose poetry of Jones’ lyrics and music are all her own — and her jazz boho sensibility suggests Mose Allison as a grandfather. Producers Lenny Waronker and Russ Titelman, who knew all about assisting quirky singer / songwriters with their visions, instructed the jazz-credentialed musicians in the recording studio to follow Jones’ stop-and-start, loud-and-soft vocalizing, after which they overdubbed string parts here and there.

The music has a sprung rhythmic feel that follows the contours of Jones’ impressionistic stories about scuffling people on the streets and in the bars. There is an undertow of melancholy that becomes more overt toward the end, as the narrator’s friends and lovers clear out, leaving her.

“Standing on the corner/All alone,” as she sings in the final song, “After Hours (Twelve Bars Past Goodnight).” It’s a long way, if only 40 minutes or so, from the frolicsome opener, “Chuck E.’s in Love,” which had concluded that he was smitten by “the little girl who’s singin’ this song.”

But then, the romance of the street is easily replaced by its loneliness.

Rickie Lee Jones produced an astounding début album that simultaneously sounds like a synthesis of many familiar styles and like nothing that anybody’s ever done before, heralding the beginning of a pivotal career of great and lasting importance, and a singular and enduring contribution to the American song book.