In the summer of 1974, Cathy and I traveled to Europe for a three-month European summer vacation, BritRail and Eurail passes in hand, this was going to be a summer vacation to keep in our memory for always.

And so it proved to be …

On another day, in another post evoking memories of our cross-continental European sabbatical, I’ll relate more stories of what occurred that summer.

Only 10 days prior to the event I am about to relate, Cathy and I had arrived in Lisbon, Portugal, alighting from a cruise liner we’d boarded in Southampton, England (passage was only 5£s, much cheaper than now).

After a couple of wonderful days in Lisbon, Cathy and I embarked on the first part of our hitchhiking sojourn throughout every portion of Portugal we could get to, finally traveling along the Algarve before arriving in the south of the country, ready to board a train to Spain.

Unfortunately, I developed some intestinal disorder or other, requiring rest and fluids.

Once Cathy could see that I was going to be fine, she left the confines of our little pensão to allow me to recover in peace, returning with stories of her having spent a wonderful day at the beach with an enthusiastic retinue of young Portuguese men, who had paid attention to and flirted with her throughout the day.

Cathy was in paradisiacal heaven; me, not so much.

Still, I was feeling better, almost recovered from my intestinal malady, and the two of us made a decision to be on our way the next morning.

To say that I was in a bad mood when I got onto the train is to understate the matter. On the way to the station, who should we run into but the very group of amorous young men Cathy had spent the previous day with, all of whom were beside themselves that this braless blonde goddess of a woman was leaving their country, as they beseeched her to “Stay, please stay.”

Alas, no luck for them; this was my wife, and we were going to be on our way.

Still suffering from the vestiges of both an irritable case of jealousy and a now worsening intestinal disorder, I was in a foul mood once we got onto the train, and as we pulled away from the station, my very loud and ill-tempered mood related in English, those sitting around us thinking that I must be some homem louco, and not wishing in any manner to engage.

A few minutes into my decorous rant, a young woman walked up to me, and asked in the boldest terms possible …

“Do you kiss your mother with that mouth?

“Huh,” I enquired?

“Do you kiss your mother with that mouth? That’s the filthiest mouth I’ve ever heard. You’ve got to teach me how to swear!”

At which point, she sat down across from me, her lithe African American dancer companion moving past me to sit next to her. “Susan. My name is Susan. This is my friend, Danelle,” she said, pointing in the direction of Danelle. “We’re from New York. We go to school there. Columbia. I’m in English Lit. Danelle’s taking dance — not hard to tell, huh? You two traveling through Europe, are you?” Susan all but shouted. “I come from a large Jewish family. You? We’re traveling through Europe together.”

And thus began a beautiful friendship.

Turns out that Susan could swear much better than I could; she needed no instruction from me. Turns out, too, that she had my number, and for all the weeks we traveled together through Europe, Susan had not one kind word for me — she set about to make my life hell, and I loved every minute of it. Susan became the sister I wished I’d had, profane, self-confident, phenomenally bright and opinionated, her acute dissection of me done lovingly and with care, to this day one of the best and most loving relationships I’ve ever had.

Little known fact about me: I love being called out by bright, emotionally healthy, socially-skilled and whole women.

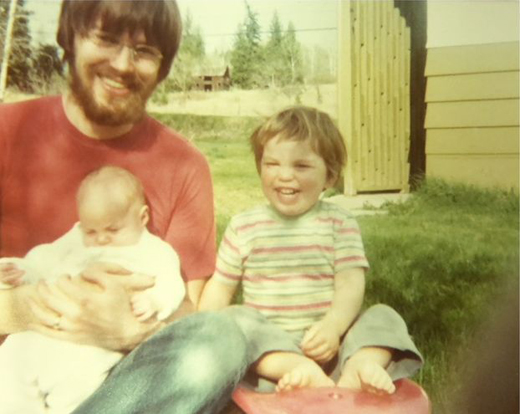

The summer of 1974, when Cathy became pregnant with Jude, on the right above.

Without the women in my life, Cathy or Megan, my daughter — when Cathy and I separated — Lori, Justine, Alison, Patricia, Julienne or Melissa, each of whom loved me, love me still, and made me a better person, the best parts of me directly attributable to these lovely women, to whom I am so grateful for caring enough about me to make me a better person.

Now onto the raison d’être of this instalment of Stories of a Life.

Once Susan and I had settled down — there was an immediate connection between Susan and I, which Cathy took as the beginnings of an affair the two of us would have (as if I would sleep with my sister — Danelle, on the other hand, well … perhaps a story for another day, but nothing really happened, other than the two of us becoming close, different from Susan).

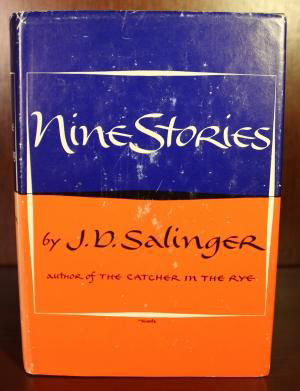

Danelle saw a ragged copy of J.D. Salinger’s Nine Stories peeking out of Cathy’s backpack.

“Okay,” she said. “In rounds, let’s each one of us give the title of one of the Salinger short stories,” which we proceeded to do. Cathy was just now reading Salinger, while I’d read the book while we were still in England, about three weeks earlier.

Cathy started first, For Esmé — with Love and Squalor. Danelle, Teddy. Susan, showing off, came up with A Perfect Day for Bananafish, telling us all, “That story was first published in the January 31, 1948 edition of The New Yorker.” Show off! I was up next, and came up with Uncle Wiggily in Connecticut. Phew — just barely came up with that one! Thank goodness.

Onto the second round: Cathy, Down at the Dinghy; Danelle, Pretty Mouth and Green My Eyes; Susan, showing off again, De Daumier-Smith’s Blue Period, “turned down by The New Yorker in late 1951, and published by the British Information World Review, early in 1952.” Me? Struggling yet again, but subject to a momentary epiphany, I blurted out, Just Before the War with the Eskimos. There we were, eight stories down and one to go.

But do you think any one of us could come up with the title to the 9th tale in Salinger’s 1953 anthology of short stories? Nope.

We thought about it, and thought about it — and nothing, nada, zero, zilch. We racked our brains, and we simply couldn’t come up with the title of the 9th short story.

We sat there, hushed. For the first time in about half an hour, there was silence between us, only the voices of children on the train, and the clickety-clack of the tracks as the train relentlessly headed towards Madrid.

We couldn’t look at one another. We were, as a group, downcast, looking up occasionally at the passing scenery, only furtively glancing at one another, only periodically and with reservation, as Cathy held onto my arm, putting hers in mine, Danelle looking up, she too wishing for human contact.

Finally, Susan looked up at me, looked directly at me, her eyes steely and hard yet … how do I say it? … full of love and confidence in me, that I somehow would be the one to rescue us from the irresolvable dilemma in which we found ourselves.

Beseechingly, Susan’s stare did not abate …

“The Laughing Man,” I said, “The Laughing Man! The 9th story in Salinger’s anthology is …” and before I could say the words, I was smothered in kisses, Cathy to my left, Susan having placed herself in my lap, kissing my cheeks, my lips, my forehead, and when she found herself unable to catch her breath, Danelle carrying on where Susan had left off, more tender than Susan, loving and appreciative, Cathy now holding me tight, love all around us.

A moment that will live in me always, a gift of the landscape of my life.