For the first five years of my life, I didn’t speak. I sang, but I didn’t speak.

Early childhood trauma, I expect — neglect, a lack of love, and darker goings on I won’t write about today — but there was nonetheless joy in my young life, the Sunshine Bread truck that would situate itself in the park at the end of Alice Street, over by Victoria and 24th, providing the young children who lived in the neighbourhood an opportunity to ride on the tiny merry-go-round on the back of the truck, the children running home to their mothers saying, “Mom, oh mom, you’ve got to buy some Sunshine Bread.”

At age five, I began to speak, first haltingly and then in full sentences. For anyone who knows me, they’d probably say that for many years now, I have been making up for the lost words of the first five years of my life.

In my home, there were no bedtime stories.

Not that either of my parents were inclined to read to my sister and I.

My father had a Grade One education, and couldn’t read. My mother had a Grade Three education, and she could read — but not to either me or my sister. Not that she was ever around the house long enough to read stories to us, even if she was so inclined — which she wasn’t.

My mother was the breadwinner in my family, working three jobs simultaneously, always, 16 hour days six days a week, with one 24-hour day. Those were in the days of the 1950s and 1960s when women were paid 35¢ an hour, hardly enough to live on.

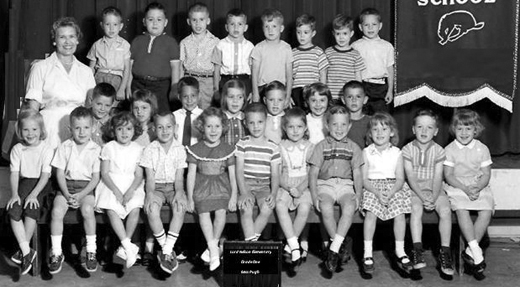

In September 1956, I entered Grade One. My mother was actually present to enroll me my first day of school at Lord Nelson Elementary, at Templeton Drive and Charles.

Grade One was, for me, a blur.

I was, I suppose, unmanageable, full of life, although I don’t have any strong memories of my attendance at Lord Nelson Elementary school, from September 1956 through June of 1957 — I had never been socialized, no one had ever made demands of me in regards of my conduct, although I would receive hard spankings at home if I got out of line.

My most cogent memories of September 1956 to June 1957 are this …

-

- Walking to school alone through billowy white fog, so thick you couldn’t see your hand in front of you, arriving at school on time, and settling into a day where I would learn nothing;

- Spending occasional afternoons at my best friend John Pavich’s home, his mother with fresh-baked, warm cookies at the ready, a glass of milk on the table. I would often stay for only a half hour, after which I would walk down Charles Street in the rain, towards Nanaimo, rumbling thunder and lightning in the steel blue skies a wondrous delight for me.

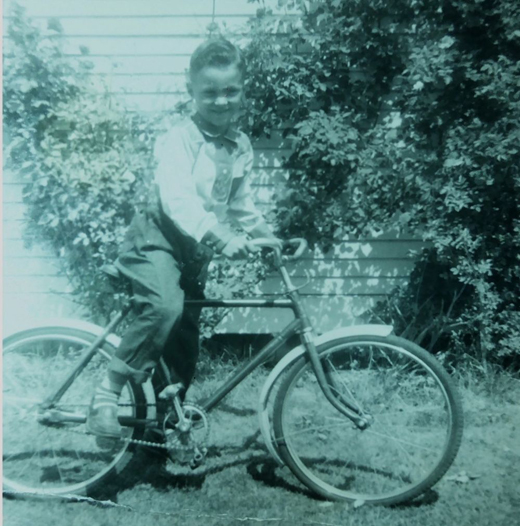

Six-year-old me, Raymond Tomlin, on my bike, outside my home, in the spring of 1957

Six-year-old me, Raymond Tomlin, on my bike, outside my home, in the spring of 1957

As the school year was ending, the sports day complete, the warm summer days having now just begun, on the last day of school in June 1957, I received my report card, taking it directly to my home as instructed by my Principal and my teacher.

There was no one home.

I played make believe all on my own. I left my report card on the kitchen table. Alone, I felt fatigued, and went to bed early on that June 30th afternoon, unsure of what the summer would bring, and what life held in store for me.

Early the next morning, following 12 hours of fitful sleep, upon opening my eyes, I was surprised to see my mother standing over my bed. She looked at me, seething, her lips pursed and tight, her face purple with rage — next thing I knew, she hit me across the face, hard. “You failed Grade One. No son of mine is going to fail Grade One. You are in for a summer of hell!”

And so it proved to be.

For the only time in all the years I lived at home, my mother left her employment, staying home with me through July and August, the renters in the downstairs suite evicted that summer, my days of hell beginning at 8am, tied to a chair in the kitchen of the downstairs suite, from 8am til 8pm Monday through Friday of each week of summer 1957, for near on 60 days — save my birthday, on August 11th, when I was given a day off.

Hour upon hour upon hour.

Over the course of the thirty-one days of July 1957, something of a miracle occurred amidst the tears, and the now lessening screams of the day: I learned to read. I learned arithmetic. I learned to print. I learned everything I had not learned in ten months of enrollment in Grade One.

By summer’s end — as would soon be discovered — I knew how to print and to write in cursive longhand, my arithmetic skills progressing far beyond basic addition and subtraction into fractions, and elementary algebra and geometry. I learned to read, I read for hours every day.

That summer I learned to love learning.

On the first day of school in September 1957, my mother — as you may have gathered, a force of nature — marched me into the school office, confronting the Principal, an anger in her that had transmogrified into rage, my mother fierce and unrelenting in a barrage of hate-filled words that filled the room, fear and dread also filling the room, the Principal clearly unsettled, teachers running towards the office to see what this mad woman who had taken control of the office wanted, was demanding.

“My son is ready for Grade 2,” my mother bellowed at my Principal, whose complexion now was ruddy, his face shuddering, his eyes wary, wide, concern — perhaps for his safety, perhaps for me – spilling out of his eyes.

“But Mrs. Tomlin, your son can’t read, he doesn’t even know the letters of the alphabet, and he doesn’t know how to do even the most basic addition and subtraction, not even one plus one equals two. I cannot place your son in Grade Two, just because you wish it to be so.”

My mother looked around the office. There was a large plaque on one of the walls, with 20 or so lines of print on the plaque.

Turning to me, pointing to the plaque, she roared, “Read it.” And I did. While I was reading the dozens of words on the plaque, my mother looked around the office, spotting a Grade 5 Math book.

Handing the Math book to the Principal, her eyes now in a squint, she demanded of the Principal, “turn to any page, ask him to solve any problem on that page.

Now!”

The principal did as he was instructed to by my mother, asking me one question after another, as he flipped through page after page of the Math book. I answered every question correctly — and quickly, as I had been instructed in my basement dungeon at home.

The Principal turned to me and said, “Wait here son, take a seat over there. Mrs. Tomlin, please come with me to my office.”

Twenty minutes later I entered Mrs. Goloff’s Grade Two class, in a portable outside along Charles Street, beginning what would be one of the best years of my life. The school had spelling bees. I won every time, not just for Grade 2, but for the whole school.

I breezed through Grade 2. Somehow, over the summer, I had gained a love of learning that resides in me still, and informs my life each and every day. I loved to read, spending hours in the school library reading whatever I could get my hands on.

The summer of 1957.

A pivotal summer in my life, not just my young life, but the whole of my life, the most impactful summer of my near 68 years on this planet since 1957. In retrospect, looking back on that summer of what began as misery and pain, and what it has meant to me over the course of the next 68 years of my life — I love my mother for what she did for me.

As I have written previously, and as I will write again, I am who I am because of the tough, caring women who have come into my life, who have been demanding of me to be my best, to give all that I can give.

As is the case with most of the women with whom I have shared my life, my mother was a tough, bright, brooked no nonsense and driven woman, someone you did not want to cross, ever, who was also — not to put too fine a point on the matter — crazy (a consequence of childhood trauma), but a survivor nonetheless, and was in her own way, loving, but in terms of the woman who was supposed to raise me, in large measure and for the most part, absent — save one particular summer, the summer of 1957.