1903: In the early part of the 20th century, my grandfather escaped the Ukrainian pogroms, an ethnic cleansing of the Jewish population that was taking place across eastern Europe that resulted in the murder of tens of thousands of Jews.

1903: In the early part of the 20th century, my grandfather escaped the Ukrainian pogroms, an ethnic cleansing of the Jewish population that was taking place across eastern Europe that resulted in the murder of tens of thousands of Jews.

Whether it be the 11 congregants at Pittsburgh’s Tree of Life synagogue who were wantonly murdered only two short weeks ago, or Jews being targeted in the alt-right rally in Charlottesville on August 11th and 12th of 2017, or the 907 Jewish refugees escaping Hitler’s Germany in 1939 who were refused safe harbour in both Canada and the United States, most of the 907 returning to their deaths in Europe, where six million more Jews were slaughtered during the course of WWII, or the fact that since 2015 hate crimes in Canada against people of the Jewish faith has risen by an astonishing 30%, the fact of the Jewish diaspora and the murder over the centuries of hundreds of thousands of Jews as “the other” in countries across the globe is a devastating and unjust historical fact for the ages.

The Hep-Hep riots in Frankfurt, Germany in 1819 that occurred amidst a climate of anti-Semitism fueled by various anti-Jewish publications. Participants in these riots rallied to the cry, “Hepp Hepp”, which may have been an acronym for “Hierosolyma est perdita”, meaning “Jerusalem is lost”. On the left, two peasant women are assaulting a Jewish man with pitchfork and broom. On the right, a man wearing spectacles, tails and a six-button waistcoat, “perhaps a pharmacist or a schoolteacher,” holds another Jewish man by the throat and is about to club him with a truncheon. The houses are being looted.

The Hep-Hep riots in Frankfurt, Germany in 1819 that occurred amidst a climate of anti-Semitism fueled by various anti-Jewish publications. Participants in these riots rallied to the cry, “Hepp Hepp”, which may have been an acronym for “Hierosolyma est perdita”, meaning “Jerusalem is lost”. On the left, two peasant women are assaulting a Jewish man with pitchfork and broom. On the right, a man wearing spectacles, tails and a six-button waistcoat, “perhaps a pharmacist or a schoolteacher,” holds another Jewish man by the throat and is about to club him with a truncheon. The houses are being looted.

First recorded in 1882, the Russian word pogrom is derived from the common prefix po- and the verb gromit’ meaning “to destroy, to wreak havoc, to demolish violently” — apparently a word borrowed from Yiddish, the term first used to describe the anti-Semitic excesses in the Russian Empire from 1881 — 1883. Antisemitism in the Ukraine has been a historical issue, as well, but became more widespread in the 20th century.

Pogroms were a generational fact of life in the Ukraine, in 1821, 1859, 1871, 1881, 1903 and 1905, across the whole of the Ukraine.

In 1903, when my grandfather was but a young Jewish teenage boy, he managed to escape the Odessa pogroms that killed thousands that year, making his way by foot to Sweden, where he hoped to find passage to Canada. Word had filtered into Europe at the turn of the last century that the Canadian government was offering tracts of land to European settlers, and it was with this fact in mind that my grandfather set about to make his way to Canada, fully aware that Jews were not included in the Canadian government’s offer of land in exchange for breadbasket farming development, in the hope of settling the Prairie provinces, and making Alberta, Saskatchewan and Manitoba part of the new country of Canada.

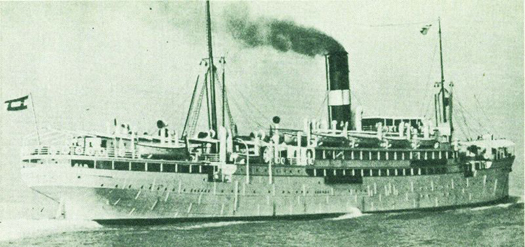

While in Sweden, my grandfather married a young Jewish woman he met while awaiting passage, and not many months later the two were boarded onto a ship sailing out of Sweden for Canada, arriving in our burgeoning new country in the spring of 1905. Irrespective of the laws of the time, and because the new province of Alberta was desperate to have their land settled, my grandparents were provided a densely treed tract, a full section of land just outside of what we now know as High River, Alberta. Over the years, one section of land grew into many, 10 children were born, five boys and five girls, the last of whom was my mother, born on March 28th, 1924.

The life was hardscrabble, even more so upon the death of my grandmother in the early winter of 1927, when my mother was but three years of age. All the children pitched in, though, creating a thriving farm — up until the Great Depression of the 1930s. By the time my mother was twelve years of age, she had struck out on her own, making a life for herself as a waitress in Drumheller, Alberta, a job she held off and on for the next fourteen years. World War II saw her moving to Vancouver to work first in the shipyards, and then in the factories making armaments — factory work a staple of her life for the next 35 years.

In 1946, my mother Mary met my father Jack, the two were married, and in 1947 my brother Robert was born, a sickly child who died three months after his birth. Escaping grief, my parents moved to Drumheller, where my mother had friends, and where her old waitress job awaited her, my father picking up what work he could. On August 9th, 1950, my mother went into labour, and had my father drive the both of them back over the deadly Rocky Mountain pass, the two arriving in Vancouver and driving directly to Vancouver General Hospital, where I was born at 2:26pm on Friday, August 11th, 1950. My sister Linda was born a bit less than two years later at St. Paul’s Hospital, on May 29th, 1952. My mother had insisted that both her children be born in Vancouver — to know my mother is to know that no one ever refused her. To this day, I am attracted only, and have found myself in loving relationships with tough, take no guff, opinionated (and, dare I say, “crazy” and just a tad, or more than a tad, mentally unstable — and, yes, I realize that’s sorta like the pot calling the kettle black … even so) women.

For the first 20 years of my life, the fact of my Jewishness was never raised with either my sister or me, not by my parents, not by my “spinster” aunt Freda (Blackerman, my mother’s maiden name), nor my aunt Anne and Uncle Dave, my uncle Joe nor any of my mother’s Jewish brothers and sisters — the quid pro quo in my family was that if my aunts, uncles and cousins wanted me to be a part of their lives, there was to be no talk of my Jewish heritage — this edict by my mother extended as well to my tall oak of a grandfather, who was every bit the sophisticated patrician Jew.

Every Sunday of our youth, my sister and I were picked up by a small school bus and transported to Sunday school, spending the rest of the day being taken to lunch, swimming, out to Stanley Park, or otherwise engaged by the members of the church. Every week I memorized and recited verses from the New Testament at Sunday school.

Now, there were some “hints” given that I might be Jewish — my mother, when she wasn’t working at one of her three jobs, loved to bake, and I grew up on a steady diet of Jewish pastries, my favourite the jam-infused hamantaschen, and jam, nut and raisin-infused rugelach, which latter small pastries I could consume by the dozen.

Growing up there was a great deal of arguing that went on between my parents, epithets thrown at my mother by my father, with the words “dirty Jew” heard on the other side of the door inside of my parent’s bedroom, words raged at my mother by my father. Otherwise, although I suspected I was Jewish, the fact was never confirmed for me growing up.

Simon Fraser University’s Louis Riel House, student family 1 + 2 bedroom residence

Simon Fraser University’s Louis Riel House, student family 1 + 2 bedroom residence

At around 10am one summer’s morning in July, 1972, while we were resident at Louis Riel House, Cathy and I received a telephone call from a woman identifying herself as my “Aunt Sally.” I took pains to explain to her that she must have the wrong number, that I had no “Aunt Sally”, to which she replied …

“I am your Aunt Sally. Your mother is Mary, who is my youngest sister. Your Aunt Freda — who all but raised you — is my second youngest sister. Summer’s you went to stay with your Auntie Anne, my sister, and your Uncle Dave, in Lethbridge. When you were younger, you stayed on my father’s farm in High River, Alberta. You know my older brother, Joe — who, when you lived in Edmonton for Grades 4, 5 and 6, helped to raise you when your mother was working three jobs, and your father was working evenings at the Post Office. Believe me when I say, Raymond — I am your Aunt Sally.”

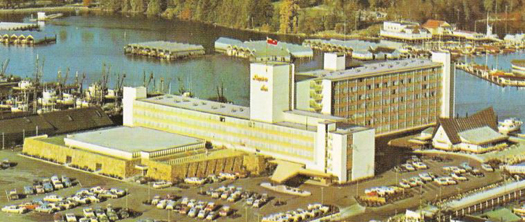

At which point, my newly-discovered Aunt Sally invited Cathy and I for lunch at the Bayshore Inn where she and her husband, Alex (Promislow) were staying while in town, on a mission to make contact with me. Aunt Sally told me that she’d already made arrangements with my mother to join us for lunch, and she expected Cathy and I to arrive at noon, where she would greet us at the entrance to The Bayshore.

Lunch was good, my mother remaining all but mute throughout the meal.

I met my Uncle Alex, Sally’s husband — who years earlier had secured the distribution rights for Lee’s jeans in Canada, a percentage of each pair of jeans, and other Lee’s products, placed into his bank account, making him a wealthy man. I heard all about my aunt, now living in Calgary, spending the early part of her life, after leaving home, in Winnipeg, where she’d met Alex. I was given the Five Books of Moses, and was provided with a more in-depth history of my family, dating back centuries, than I ever could have hoped for. Through it all, my mother denied her Jewishness — she readily admitted that Sally was her sister, but insisted she had been adopted, and had not a drop of Jewish blood in her, and as an atheist had never been a member of any church, never mind a synagogue, which notion she told us she found offensive and off-putting, her so-called “heritage” a complete and utter lie. My aunt Sally simply rolled her eyes, and harrumphed a bit.

I stayed in touch with my aunt Sally and Uncle Alex for another 15 years, but eventually lost touch with the both of them.

Growing up, I apprised both Jude and Megan of their Jewish heritage — much to their mother’s chagrin, my children’s mother both anti-religion and an avowed atheist. Hanukkah, one of the lesser Jewish holidays, was their favourite, occurring as it did in December, and generally just before Christmas. Jude and Megan loved receiving one small gift each day of Hanukkah, and enjoyed lighting the menora, as well. We always attended cultural celebrations at the Jewish Community Centre, dancing up a storm.

Jude and Megan had Jewish friends, and attended at various bat and bar mitzvahs, but did not have one of their own (their mother would have had a conniption fit!). During Passover, we were invited to friend’s homes for Seder, at which time our Jewish friends explained the importance of Passover, and what it meant to people of the Jewish faith.

I have come to believe that the immense amount of energy that I have brought to the tasks of my life — as is the case with my daughter, who possesses the same capacity as me to work days on end with little or no sleep, while maintaining both a high energy and output level — derives from the Jewish blood that courses through my veins. For my children, their Jewishness is not a factor in their lives, as is the case with my grandsons.

Still, I consider myself to be Jewish — my mother was Jewish, and Judaism is a matriarchy, so I am very much a Jew, even if my mother denied her Jewish heritage to her dying day. For my younger sister Linda, her Jewish heritage plays no role in her life, nor in that of my two nieces.

I have decided to take classes with Rabbi Dan Moskovitz in the new year to become better acquainted with my heritage — a bit late in my life, but better late than never. And, of course, at the invitation of my friend Jacob Kojfman, I will once again attend the Dreidels & Drinks Hanukkah celebration, for me the low-key, warmly inviting, edifying and humane event of the holiday season, to which are invited every federal, provincial and Metro Vancouver elected official, providing an opportunity to converse and interact across political boundaries (the number of political figures I introduced to one another, avowed “enemies” at first introduction, and only a few minutes later best of friends, person after person approaching me to say, “Thank you for that introduction, Raymond — who’d have thought that —- and I had so much in common? We got along famously!”

And, really, when you get right down to it, isn’t that what the holiday season is all about — peace, love, understanding, brother-and-sisterhood.