In 1972, upon returning from our two month sojourn to Mexico, Cathy and I became vegetarians. While traveling through Mexico, we were uncertain about the provenance of much of the food we ate, but were certain that far too much of what we consumed as “meat” was not meat from a cow.

Once back in Vancouver, Cathy and I were made aware of a “buying group” that had been formed by a friend of a friend, a sweet-natured, calm and centered, energetic and idea-filled fellow by the name of Murray Head. Murray had put together a group of 10 couples who would order food each week collectively, mostly produce, top quality from the best suppliers, as well as cheeses and a vast array of food staples of the very highest quality.

Cathy and I joined up with Murray and his wife, and eight other couples in May 1972 into this new, largely vegetarian collective buying group.

As word spread throughout the community about our newly-formed “buying group”, friends, neighbours, dope-smoking Cosmic League baseball players, and activists wanted in, and joined with us to create a much larger buying group, which by mid-July had become the Tillicum Food Co-operative.

With the support of Dave Barrett’s groundbreaking and leftist provincial government — a grassroots-based government if there ever was one, in Canada or elsewhere — $300,000 was granted by the government to the nascent group of activists who were organizing for change around food.

Norm Levi, British Columbia’s first Minister of Human Resources, was assigned the task of liasing with the members of the now burgeoning Tillicum Food Co-operative. A warehouse on Vancouver’s eastside was secured, two blocks north of the Waldorf Hotel, just off Hastings Street.

As the new Tillicum Food Co-op was realized, the food-buying club was re-organized into neighbourhood collectives, organized, run and operated by family groups with friends and neighbours in each of Vancouver’s 23 neighbourhoods, each collective run autonomously, but coming into the Tillicum Co-op warehouse each week to pick up their weekly food order.

Initially, collectives collated and submitted their orders for bulk pre-ordering with the other collectives. Responsibility for ordering and sorting the food for the whole club rotated among the various collectives.

As it happened, and quite fortuitously, the founders’ experiences with activism and community organization brought forward a skill-set that proved useful to starting a co-operative. Together, our collective experience brought communication, group decision-making, and leadership qualities.

Through trial and error, good-naturedly we learned how to start, manage and operate as a truly democratic, grassroots, member-run co-operative.

By September 1972, though, with dozens of collectives now spread across Vancouver, and beyond, moving into all of the cities across Metro Vancouver and into the Fraser Valley, a decision was taken to hire a “co-ordinator,” someone who would oversee the growth of the burgeoning grassroots co-operative movement in Vancouver. The “Co-ordinator” would be the de facto Chief Executive Officer, responsible for liaising with suppliers, organizing the collectives, overseeing the distribution of food, publishing a magazine, and working with all levels of government to grow the movement into a much larger social-environmental justice movement.

The individual who was chosen as the Tillicum Food Co-operative’s first co-ordinator was a 22-year-old Simon Fraser University student, a fellow by the name of Raymond Tomlin. From the time of his hire and over the course of the next year, Tillicum grew into a province and nationwide co-operative movement, with collectives in every town, village, community and city across the province, into the prairies, as well as into Washington state.

The thousand dollar a week buying club that had begun in May 1972, by September 1973 had become a thriving, two million dollar a month business, working with government to create British Columbia’s first co-operative child care centres, securing funding for our province’s first recycling depot, creating the Wild West Organic Co-operative (western Canada’s first organic food distributor), going on to purchase farms, setting up furniture building, tool and automotive co-operatives, and working with the provincial, and more, the federal government, to create a made-in-Canada solution for the provision of member-run affordable housing.

And thus by 1977, Canada saw the approval of our nation’s first housing co-operative, the Amor de Cosmos co-op in Vancouver’s Champlain Heights neighbourhood, followed by the creation of the Kitsun Co-op on West Broadway in Vancouver, Canada’s first solar-powered housing co-operative.

Halcyon days those, when all you had to do was come up with an idea, and with the support of Premier Dave Barrett’s and Prime Minister Pierre Elliott Trudeau’s governments — federally, Mr. Trudeau initiating virtually all of the policies of David Lewis’ federal New Democratic Party — there were jobs aplenty, significant funding for federal job creation programmes for activists, federally administered job programmes like the Local Initiatives Programme (LIP) that gave priority to “funding non-profit organizations that would provide useful services or facilities to the community,” and the longer term Local Employment Assistance Programme (LEAP) that not only created hundreds of thousands of jobs for activists across Canada, but in Vancouver funded almost all of the jobs at the Tillicum Food Co-operative.

1972: A fuzzy picture of a long-haired Raymond Tomlin, and exquisite Cathy McLean

1972: A fuzzy picture of a long-haired Raymond Tomlin, and exquisite Cathy McLean

Note should be made that the always brilliant and phenomenally talented Cathy McLean (my spouse and love of my life) wrote all of the grant applications — of which there were hundreds — every single one of the grant applications she submitted approved by the federal government.

1973: Grandview United Church, Venables & Victoria, became Vancouver Free University

1973: Grandview United Church, Venables & Victoria, became Vancouver Free University

The LIP and LEAP programmes were also responsible for helping to acquire a closed and forlorn church at Venables and Victoria Drive, which first became an open university, and soon after became known as the Vancouver East Cultural Centre, and then simply, in recent years as, “The Cultch.”

Paul Phillips, one of the founders of Vancouver’s Fed-Up Food Co-operative Wholesaler

Paul Phillips, one of the founders of Vancouver’s Fed-Up Food Co-operative Wholesaler

A group of activists lead by Dana Weber, Ros Breckner and Paul Phillips left the now thriving Tillicum Food Co-operative to form the Fed-Up Food Co-op Wholesaler, importing food stuffs from across the globe, and acting as a supplier to the Tillicum Co-op. Fed Up was the first North American wholesaler to sign a contract that would bring sultana raisins from Australia onto this continent. Where Tillicum remained responsible for distributing food throughout the Metro Vancouver region, Fed Up took on the job of distributing food across the province, western Canada and down into the United States, and growing the food co-operative movement globally.

Simon Fraser University’s Louis Riel House, student family 1 + 2 bedroom residence

Simon Fraser University’s Louis Riel House, student family 1 + 2 bedroom residence

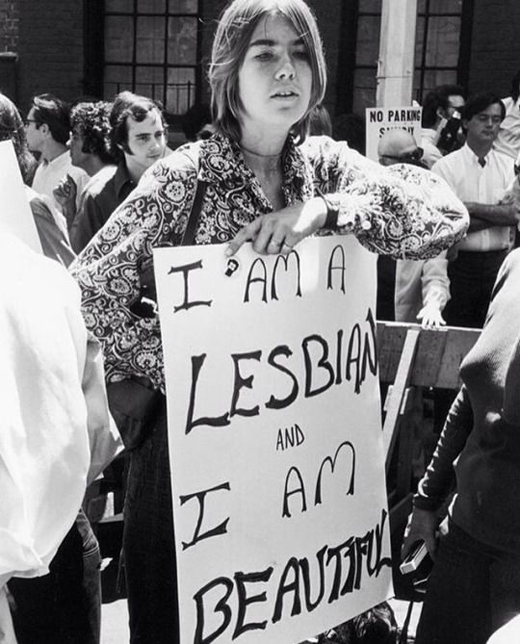

Meanwhile, there was nascent women’s and LGBTQ movements that were just getting underway. Throughout the 1970s, I recall that each Wednesday evening that Cathy would leave our apartment to meet with almost every woman who lived in Louis Riel House — the 148 one-bedroom and 61 two-bedroom student apartment residence located at Simon Fraser University’s Burnaby Mountain campus — for what was termed consciousness-raising.

The “consciousness-raising” of the day was not limited to white, cis-gendered women, however. No, as I wrote above, there was along with the women’s movement, a burgeoning & activist LGBTQ movement in our city.

And thus, finally on VanRamblings, the raison d’être as to why I am writing today’s Story of a Life, because today’s story is one that has remained deep within me all of my adult life, and helped to define my involvement over the past near 50 years in both the feminist & LGBTQ social justice movements.

In the autumn of 1972 I made the acquaintance of a group of activist women who had formed their own collective in the Tillicum Food Co-op.

Young, bright, passionate, articulate, as I am wont to do, I fell in love with each of these women who supported me in my various endeavours, tough, strong, take no guff women who were surprisingly gentle and supportive of me, giving instruction to me as it was necessary (which was probably more often than I would admit even now). The group of us became fast friends, as we worked together to build a fairer, more just and inclusive society.

Now, each of these women, average age about 22, were strikingly attractive in the most usual sense, and drew a great deal of unwanted attention from men. To say that the early 70s were the days of rampant sexism is to understate the matter. These were antediluvian times in the history of the women’s movement, and in our collective history. The women in the Women’s Collective were able to handle whatever situation came their way, though, and nothing too untoward ever occurred, until …

The Women’s Collective was an overtly political collective. Not only were they progenitors of the women’s movement in Vancouver, they also wished to be progenitors of the LGBTQ movement, although all the women were white, educated and decidedly heterosexual.

The Women’s Collective, though, still took on the goal of championing LGBTQ issues, and lesbianism in particular, by adopting lesbianism as a personal and political endeavour. To thwart any interest by men, a decision was taken by each woman, who when I first met them weighed in at about 110 pounds sopping wet, to gain 60 pounds apiece — and they did.

By February 1973, each woman weighed in at about 185 pounds.

In addition to gaining weight, and becoming an overt, in-your-face lesbian collective, the Women’s Collective undertook a military-style training regimen, a three-month long boot camp that even though the women were now of hefty frame, they were also as strong, in actuality much stronger, than any man involved with either Tillicum or Fed Up Food Co-operative.

From autumn 1972 to winter 1973 I saw the transformation, and it was something to behold, a form of experiential personal theatre made live that was amazing to watch unfold. The women continued to be kind, tending to a quiet and less boisterous nature — although fun to be around, and at the monthly drunk-a-thon dances we had in the Tillicum warehouse, great dancers each and every one of them, lithe despite their new bulkiness.

Still, as I say, these were sexist and regressive times in the early 1970s.

Women were undermined as a matter of daily intercourse in the life of our society, tended to have what they said readily dismissed, and were regarded by most men of the time as little more than sexual playthings.

Not so for the politically active lesbian women in the Women’s Collective.

In Vancouver this past year, a new movement of change has emerged, the sort of revolutionary change many of us felt and lived in the late 1960s and early 1970s, this new Vancouver-based movement identifying themselves as TeamJean, a cadre of activists who have organized around Order of Canada recipient and veteran community and anti-poverty activist, Jean Swanson. What I find so becoming and hopeful about the, mostly, young people involved with TeamJean is not just their revolutionary fervor and their work towards creating substantive change in our society, and change now, but in how much fun they’re having in organizing for change, how each of them see the necessity of theatre as a necessary communications tool to get their ideas across in a humanist and non-threatening manner.

There is an excitement within TeamJean that is wholly inspiring, an excitement I haven’t seen, felt and experienced in more than 40 years.

In the 2018 Vancouver municipal election, I have been writing that Derrick O’Keefe, working with organizers within TeamJean like Sara Sg, Chanel Ly, Fiona York, Maddie Andrews, Duncan Martin, Selina Crammond, Riaz Behra, Luis Porte Petit, Ngaire Leach (the graphic designer behind the Jean Swanson logo, and all of TeamJean’s visual design), Shawn Vulliez, Aiden Sisler, Darlene Alice Bertholet, Beverly Ho, Devin Gillan, Alex Kennedy, Ishman Bhuiyan, Jorj Tempul and Qara Maristella believe not just in activism and activism with a conscience, but in the transformative power of theatre, art, song, dance and plain good fun towards changing and helping minds grow, to bringing people along with them into a new era of peace, social justice and inclusion, that aims to serve the many over the few.

In February 1973, a meeting of the collectives involved in the Tillicum Food Co-operative movement was called, the meeting taking place in a workshop space on 2nd Avenue just west of Main. These meetings were held monthly, chaired by me, where we shared ideas on how to grow the co-op movement, not just the food co-op movement, but movements in general.

Of course, a cadre of my favourite women in the Women’s Collective were present, all bulky and fine and in good spirits, on their home turf in their workshop space, and ready with a plethora of ideas on a panoply of activist fronts. The Women’s Collective had proven central to the success of the Tillicum Food Co-op, and the soon-to-be Fed Up Co-operative — without their support, counsel and energy, I’m not entirely sure that the Tillicum Food Co-op would have grown as it did in the first year, and beyond.

So, there we were on this chilly Tuesday evening in early February 1973, in a dimly lit workshop space, approximately 75 chairs set out, me at the front, collective members from across the Lower Mainland settled into their chairs, the women in the Women’s Collective “patrolling” the meeting, none of them seated, almost a security force, in case such was needed.

There was talk of forming a camping and adventure equipment co-operative, which eventually became the Mountain Equipment Co-op. There was talk about working with the provincial government on creating child care in our province, which occurred in 1974, when Norm Levi assigned $100 million to the creation of child care centres throughout the province. As usual, the meeting was positive and directed, orderly and respectful.

Except …

There was one man, sitting off to my left, in the second row who, when one of the women in the Women’s Collective offered up an idea that met with support, but debate from some of those present, that when it came time for this man to speak, he looked directly at the woman who had made the suggestion, and started off his address to her, saying, “Hey, douchebag …”

In a millisecond, a woman in the Women’s Collective who’d been standing behind him, pulled his chair back on its back legs, his feet now dangling, while another woman in the collective approached him, pulling down his pants and his underwear, and when this was accomplished, yet another woman in the collective grabbed his flaccid penis, pulling it taut while also pulling up his scrotum, and then placing the tip of a knife under his scrotum in the perineal region midway between his anus and his genitals, the woman who had pulled down his pants and underwear now looking directly at this now formerly recalcitrant man, and asked, “Did you want to repeat yourself? Did you want to address my friend using the pejorative you employed just a moment ago? You called my friend what? I’m waiting …”

All of the above had occurred in much under 60 seconds.

The formerly surly man of intransigent nature was mute, not frightened exactly but more contemplative than anything else. He shook his head, and finally uttered, “No, I have nothing to say other than, I’m sorry. It’ll never happen again. I promise.” And, in all the time to come it never did.

As quickly as the errant man had been approached, the women withdrew, his chair let down, aid given to pull up his pants, those 75 Tillicum members in attendance acknowledging what had occurred between the Women’s Collective and the disagreeable man, for what it was: theatre.

Of course, change doesn’t happen in a day, it is long and arduous and hard fought for — but occurs most often with action and a degree of humour.

Some year later, I recall working in the offices at the Fed Up Food Co-op on Scotia Street, and walking down into the warehouse, where 80 pound sacks of oatmeal were being carried from one end of the warehouse to the other. On one memorable occasion, I saw a young, petite woman quite easily carrying an 80-pound oatmeal sack on her back, as a man came up to her and, gallantly I’m sure he thought, looking at the woman, saying to her, “I can do that for you. I’ll take the sack, if you’ll let me.” And she did.

The man took the cumbersome 80-pound oatmeal sack, and struggled to carry it across the warehouse. Meanwhile, the woman who had given up the oatmeal sack had gone back to pick up a 100-pound sack of wholegrain flour, and as the man continued his struggle with the heavy oatmeal sack, the woman sailed on past the man with a light as a feather 100-pound flour sack on her back, glancing back at the struggling man saying, “Thank you,” and then proceeding to the other end of the warehouse with her burden that was not a burden at all, but a metaphor for change and growth, and the doctrine of a necessary and revolutionary change of consciousness.