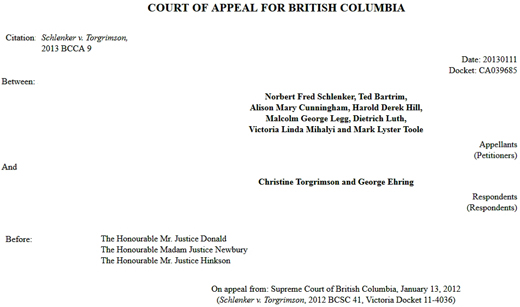

Wednesday evening, former Vancouver City Councillor and respected civic affairs barrister Jonathan Baker wrote to VanRamblings to apprise us of Schlenker v. Torgrimson, a BC Court of Appeals case heard in 2013, which ruled that Salt Spring Island Councillors were in a conflict of interest arising from a direct or indirect pecuniary interest, in respect of having voted to award two service contracts to societies of which they were directors (see Reason for Judgment in the Schlenker v. Torgrimson link above).

In the written reasons for Judgment in the BC Court of Appeals, the Honourable Mr. Justice Donald — concurred in by The Honourable Madam Justice Newbury, and The Honourable Mr. Justice Hinkson — wrote …

[1] Elected officials must avoid conflicts of interest. The question on appeal is whether the respondents were in a conflict when they voted to award two service contracts to societies of which they were directors. In the words of s. 101(1) of the Community Charter, S.B.C. 2003, c. 26, did they have “a direct or indirect pecuniary interest in the matter[s]”?

[5] The penalty for conflict is disqualification until the next election.

[6] I would allow the appeal and declare that the respondents violated the Community Charter.

CityHallWatch has published a backgrounder on the case, with a link to a Fulton and Company LLP three-page summary of Schlenker v. Torgrimson.

Arising from an at-length conversation VanRamblings had with the learned Mr. Baker, a determination was made that it may very well be that Schlenker v. Torgrimson could be the determining case law that, upon adjudication and a ruling on the matter before a Justice of the Supreme Court of British Columbia, could result in an order of the Court that would prevent Vision Vancouver City Councillors who are elected in the next term from seeking a further term of elected office, in 2018.

Mr. Baker offers this précis of Schlenker v. Torgrimson …

The Court of Appeal said direct or indirect pecuniary interest doesn’t just refer to money, that a politician has a fiduciary duty to the Council on which they sit as a member, without built-in bias.

The bias that arises from a member of Council serving two masters is, in Schlenker v. Torgrimson, one, perfectly benign in relation to the environmental group of which he is a member, and his duty to his taxpayers, which loyalties are divided and in conflict.

The Justices held that it was important the Court come down with a decision. Paragraph 34 of the Judgment reads, “to prevent elected officials from having divided loyalties” in deciding how to spend the public’s money, one’s own financial advantage can be such a powerful motive, that putting the public interest second leads to a conflict. The Court must then rule that the Council member could not run for a succeeding term of office.

The benefit — or direct or indirect pecuniary interest — potentially derived by Mr. Meggs, and Vision Vancouver City Councillors, would be the monies received in compensation for duties performed as an elected official.

A direct conflict link, and a decided conflict of interest by Vision Vancouver, might be made — involving the receipt of monies from CUPE 1004 in exchange for favours or benefit, the commitment made to CUPE 1004 by Geoff Meggs on behalf of Vision Vancouver that there would “no contracting out”, this commitment to members of CUPE 1004 made in advance of the bargaining of the upcoming December 2015 collective agreement, and payment in the form of monies paid by taxpayers to elected officials, in this case the Vision Vancouver members of Vancouver City Council.

As per Bob Mackin’s article in the Vancouver Courier, the CUPE 1004 local donated $102,000 to the Vision Vancouver re-election campaign, as was made explicit, in exchange for a commitment by Vision Vancouver not to contract out the jobs of city workers.

The Criminal Code of Canada, Section 123, reads …

Every one is guilty of an indictable offence and liable to imprisonment for a term not exceeding five years who directly or indirectly gives, offers or agrees to give or offer to a municipal official or to anyone for the benefit of a municipal official — or, being a municipal official, directly or indirectly demands, accepts or offers or agrees to accept from any person for themselves or another person — a loan, reward, advantage or benefit of any kind as consideration for the official.”

Mr. Baker suggested to VanRamblings that in the case of CUPE 1004’s commitment to the payment of monies to Vision Vancouver — the details of which are explicated in an October 16, 2014 Bob Mackin article in the Vancouver Courier — the circumstance is worse, as in …

“We’re going to give you money. There are strings attached. And they respond, ‘Yeah, we know.’ So, it looks like you have a contract, which is a horrible breach of their fiduciary duty to those citizens who elected them to office, and the populace of the city, in general.”

Section 38 of Schlenker v. Torgrimson was, in part, based on the Ontario Divisional Court ruling in Re Moll and Fisher, which reads …

This enactment, like all conflict-of-interest rules, is based on the moral principle, long embodied in our jurisprudence, that no man can serve two masters. It recognizes the fact that the judgment of even the most well-meaning men and women may be impaired when their personal financial interests are affected. Public office is a trust conferred by public authority for public purpose. And the Act … enjoins holders of public offices … from any participation in matters in which their economic self-interest may be in conflict with their public duty. The public’s confidence in its elected representatives demands no less.

Given all of the above, VanRamblings has now come to believe that Kirk LaPointe was right when he wrote in his opinion piece in The Province …

Vision Coun. Geoff Meggs, speaking for Vancouver Mayor Gregor Robertson, recently told a meeting of CUPE Local 1004 that the mayor was committing to not contract out any other city jobs. In turn, Vision was given financial and political support. No wonder Vancouverites don’t trust city hall under Vision. Corruption corrodes confidence and this commitment smacks of political backroom deals of yesteryear.

It puts Vision’s interests ahead of the city’s and taxpayers.

Being clearly beholden to the city’s workers right now is an irresponsible service to the city. The union is approaching contract discussions, and any early definition of the city’s bargaining position is a breach of fiduciary duty.

Once again, as happens on occasion, VanRamblings finds itself in the position of having to offer a mea culpa to an aggrieved party, in this case Non-Partisan Association candidate for Mayor, Mr. Kirk LaPointe.

We apologize, unreservedly, to you Mr. LaPointe. You were right, you are right. In fact, VanRamblings has now come to believe that the actions of Councillor Meggs represent, as you write, “an irresponsible service to the city”, and that the verbal contract agreed to by Councillor Meggs, on behalf of the Vision Vancouver municipal political party of which he is a member, may and perhaps does, in fact, represent a breach of his fiduciary duty to the electorate, such matter yet to be officially determined in a court of law.