Ani DiFranco first played the Vancouver Folk Music Festival in 1992, a 22-year-old up-and-coming singer-songwriter who drove herself from concert to concert across the North American continent, billing herself as the “Little Folksinger” (Ms. DiFranco is 5’2″ tall), in the process creating her own record label, Righteous Babe, allowing her significant creative freedom.

Through the Righteous Babe Foundation Ms. DiFranco, long a political and cultural activist, has backed grassroots cultural and political organizations supporting causes including reproductive rights, gay, lesbian and women’s issues, in 2004 touring Thai and Burmese refugee camps to learn about the Burmese resistance movement and the country’s fight for democracy, in recent years lending her voice and presence to the Women’s Lives Marches in Washington, DC, tangibly demonstrating her belief that the personal is, now and forever, political.

When she first appeared on the various Vancouver Folk Music Festival stages, she immediately connected with the rapturous festival audiences, and that grassroots connection has endured here and far beyond.

Over the years, Vancouver’s Folk Music Festival stages have also been gay-friendly: in addition to Ani DiFranco, Canada’s own k.d. lang, the Indigo Girls, Nanci Griffith, Holly Near, Janis Ian, Tret Fure, Melissa Ferrick, Toshi Reagon, Jill Sobule, Cheryl Wheeler, Patty Larkin (and dozens more) have graced festival stages, and delighted and moved audiences.

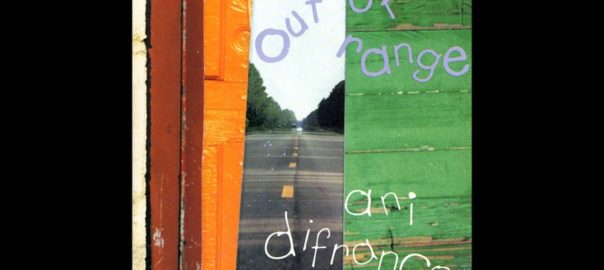

When she first emerged in 1990, Ani DiFranco had an immediate appeal to misfits. After débuting her eponymous solo album that year, she followed it up with six more in rapid succession, taking only a brief one-year breather in between 1996’s Dilate and 1998’s best-selling Little Plastic Castle.

Ms. DiFranco’s folk-punk aesthetic (complete with staccato finger pickings and spoken word spun into song) was especially exciting to queer women, who rarely had the opportunity to sing along with inclusive lyrics like Ms. DiFranco’s. Not only was she a poetic lyricist, she had a handful of songs that were explicitly about other women, using female pronouns.

Success has been somewhat bittersweet, though, for the folk-punk feminist and rabble-rousing storyteller.

Early on, Ms. DiFranco was open about her bisexuality (she’s married to producer Mike Napolitano, with whom she has two children), but in 2015, she told the LGBT blog GoPride.com she’s “not so queer anymore, but definitely a woman-centered woman and just a human rights-centered artist.” This didn’t sit too well with the lesbian and otherwise queer fanbase she’d drawn from the beginning.

Ani DiFranco is set to release a memoir entitled No Walls and the Recurring Dream, recounting her early life from a place of hard-won wisdom, combining personal expression, the power of music, feminism, political activism, storytelling and philanthropy, while chronicling her rise to fame with an engaging candor, a frank, honest, passionate, touching and humorous tale of one woman’s eventful coming of age story and radical journey, defined by her ever-present ethos of fierce independence.

Viking Press will release Ms. DiFranco’s book next month, on Tuesday, May 7th, a week from this coming Tuesday.