Movie musicals are often a polarizing topic.

People either love them or hate them, and even those that love them are critical of on-screen adaptations of their favourite stage shows.

In recent years, Hollywood hasn’t had a great track record of adapting musicals from the stage to the screen in a way that works, and many movie musicals in past years have been criticized for not having that certain something that makes the onstage musicals feel so special and unique.

That was the case until three years ago, 2021, which apparently became the year when Hollywood figured out how to make a good movie musical.

As the musicals that were made that year were, sadly, not big box office hits, nor successful streaming, movie musicals have once again faded from our screens, both in our local multiplex, and on Netflix and other streaming platforms.

Still and all, if you love musicals, you can still take heart with the rich and glorious history of the musical, in whatever form it has taken cinematically.

Regardless of their box office success, there were there a great many 2021 musicals that were Oscar nominated — In The Heights, Dear Evan Hansen, tick, tick…BOOM!, West Side Story, and even Encanto (which wasn’t derived from a stage play). For the most part, they were well executed, and loved by critics, if not by a mass, anticipatory audience.

For the past century, the Hollywood musical has been recognized as a distinguished part of our movie history, playing an integral role in the evolution of movies during the 1920s through 1950s, til now.

It wasn’t until 1927 that Warner Brothers first introduced to the big screen singing along with sound in their release of The Jazz Singer; a remake of the Broadway musical of the same name.

The late 1920s brought difficult economic times, and a worldwide Depression.

It was during this time that Hollywood came to the public’s rescue with the dynamically entertaining diversion of the Hollywood musical.

Hollywood studios began to release a plethora of musicals which offered the movie-going public a chance to temporarily escape from the dire economic issues that had the world in its grip.

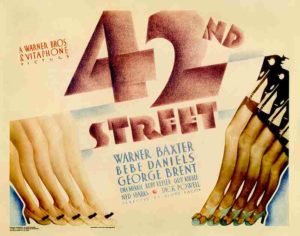

In the 1930s, with Warner Brothers’ acquisition of choreographer Busby Berkeley, the musical genre was truly born with the release of popular musicals like 42nd Street, Bright Lights, and Gold Diggers.

Capping the decade was 1939’s The Wizard of Oz, still one of the classic musicals that continues to entertain audiences today.

It was during the 1940s that the Hollywood musical really came of age, and the popularity of the movie musical continued right through the 1950s.

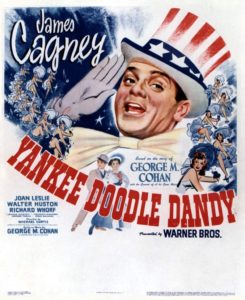

One of the more popular 1940s musicals was Yankee Doodle Dandy, a film that introduced movie lovers to a young James Cagney who gave a performance that earned him an Oscar. Another popular 1940s title, long a holiday tradition, is The Bells of St. Mary’s.

Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer embraced old-fashioned musical films in the ’40s and ’50s, furthering the boundaries of the musicals, with stars like Judy Garland, Fred Astaire and Mickey Rooney leading the way.

Starting with Meet Me in St. Louis (Vincent Minnelli, 1944), MGM began producing some of the most popular films of the era, including Easter Parade (Walters, 1948), An American in Paris (Minnelli, 1951), and Singin’ in the Rain (Kelly and Donen, 1952).

Marilyn Monroe brought a new element to the musical movie during the 1950’s.

This was also the time to bring Broadway to film in movies such as Oklahoma! and Guys and Dolls.

Elvis also started to make the big screen his home, which many believe signalled the beginning of the end for the genre.

Through the 1960s, though, the adaptation of stage material for the screen remained a predominant trend in Hollywood. West Side Story, My Fair Lady, The Sound of Music, and Oliver! were all adapted from Broadway hits and each won the Academy Award for Best Picture.

The genre changed slightly during the 1970’s, where in some cases, such as Saturday Night Fever and Tommy, the stars were not the singers. The movie plot was being driven by song, but in a pre-recorded way.

There were a few musicals to note in the ’80s, like Annie and Purple Rain, but for the most part, the entire genre had changed to musicians supplying the music.

With the arrival of the early 1990s, one of the more successful modern-day musical movements emerged: Disney’s animated musical blockbusters, including such films as The Little Mermaid, Aladdin and The Lion King, all released in rapid succession, amassing an enormous fan base along the way.

In 2000, let us not forget the Coen Brothers’ O Brother, Where Are Thou?

Although the animated musical film has become a popular route for the genre in recent years, the success of musicals like Chicago, Rent, Sweeney Todd, and Les Misérables seems to indicate that large scale, live action musical productions are still very much relevant to film today.

In 2006: John Carney’s début film, Once, with Glen Hansard and Markéta Irglová.

In 2017, three musicals were nominated for Best Motion Picture – Musical or Comedy at the Golden Globes: Florence Foster Jenkins, La La Land, and Sing Street, with La La Land taking home the award (well, sort of).

Although musicals might not necessarily find success in terms of receiving the most awards recognition, they are nonetheless popular and enjoyed by audiences.

Once upon a time, huge, spectacle musicals were the backbone of Hollywood.

The pandemic year of 2021 offered Hollywood a chance to return to the glory days of the 1930s Depression era musical, allowing audiences to reacquire a taste for the musical, to help lift of us out of the malaise that had us in its grip.

The Hollywood musical has always offered viewers a page out of movie history, memories that will forever be captured on film, and musical films that will continue to be enjoyed by audiences around the world.