Prior to the outbreak of World War II, 83% of Canadians lived in the rural areas of Canada, mostly as members of farming families, leaving only 17% of the population to reside in hub cities like Montréal, Toronto & Vancouver, with much lesser populations in the prairie cities, and provincial capitals.

Following the end of the overseas conflict, with the industrial heartland of Germany, not to mention a great swath of Europe, and the production capitals of Japan leveled by the ravages of war, North America soon became the industrial heartland, and the bread basket, for the world.

Soldiers arriving home from Europe, rather than choosing to return to the farming communities from whence they had come prior to the outbreak of the conflicts in Europe and Japan, remained in the cities, many of them choosing to marry. The late 1940s and 1950s witnessed an unprecedented mass in-migration of highly-skilled, mostly European, industrial workers to populate the factory floors, and run the means of production.

In the 1950s, with a burgeoning population requiring housing, Vancouver became one of the three major Canadian cities to experience a building boom, a boom that has not been equaled since on our shores. The form of development chosen? The single-detached family dwelling. Apartment buildings were few and far between, the Vancouver economy thrived, and new homes were offered on the market at a $2000 price point, or less.

In Vancouver, as was the case across the North American continent, the populace adopted the much-ballyhooed economic notion of “a car in every garage” (requiring that a house be attached to that garage). With personal motor vehicles all the rage, the population was encouraged to consider streetcars as a relic of the past, an outmoded means of transportation.

In the mid-1950s, the Interurban streetcar service — a service that had been inaugurated in 1891 to transport British Columbians across the southwest region of our province — was moth-balled, the entire service dismantled, track-by-track, the invaluable, inexpensive and well-utilized Interurban streetcar lines seemingly gone forever.

Vancouver’s Raymur Housing Project — social housing in Vancouver, circa 1970

In the 1950s, provincial government social planners spanning the nation, in concert with their federal government counterparts, set about to create “urban social housing complexes” to house the provinces’ poorest citizens. In doing so, Canadian provinces adopted the multiple family dwelling, or “apartment”, model as the housing form to shelter the indigent population. In U.S. cities like Detroit and Chicago, we are much more apt to call these “urban social housing complexes” by a more colloquial name: ghettos.

In Toronto, the constructed, soon-to-be-crime-ridden, concrete tower neighbourhood was named Regent Park. In Vancouver, the new community to house the poor was named The Raymur Project, with residents from across British Columbia brought to Vancouver to live in the newly-conceived, virtually free urban social housing complex.

As is so often the case with our current gentrifiers without a heart Vision Vancouver civic administration, folks already resident in the neighbourhood were displaced when the construction of Raymur commenced — an estimated 860 full-time residents of the downtown eastside neighbourhood were left to the vagaries of 1950s Vancouver to find alternate accommodation on their own, over half of their number longtime residents of the community, of Chinese descent.

Both social housing projects failed in their initial iterations, developing into crime-infested urban ghettos, as had been the American experience.

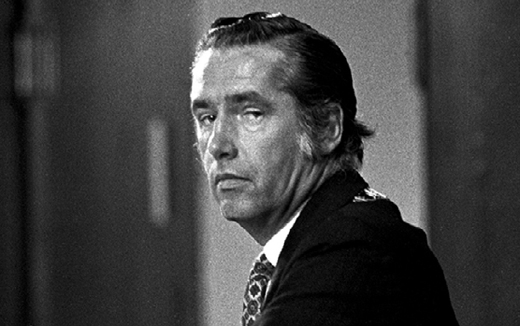

Tom ‘Not So Terrific’ Campbell, controversial Vancouver mayor, in office from 1966 to 1972

In 1966, running as an independent, a brash and confrontational Tom Campbell defeated sitting NPA mayor, Bill Rathie, to become Vancouver’s 31st mayor. From the outset, Campbell’s ascension to the Mayor’s office heralded a pro-development ethos that would make even Vision Vancouver blush, in the process advocating for a freeway that would cut through a large swath of the downtown east side, require the demolition of the historic Carnegie Centre at Main and Hastings, and bring about the construction of a luxury hotel at the entrance of Stanley Park, as well.

Vancouver’s West End neighbourhood, 1960, pre-high-rise construction. Photo, Fred Herzog.

In the West End, where Campbell — a wealthy, successful developer — owned substantial property, the newly-elected Mayor all but ordered the demolition of almost the entirety of the well-populated West End residential neighbourhood — housing mostly senior citizens in their single detached homes — as he set about to make way for the rapid construction of more than 200 concrete high-rise towers, transforming the West End forever.

All of these “changes” augered wild controversy among large portions of the Vancouver populace, leading to regular, vocal and sometimes even violent protests throughout Campbell’s treacherous tenure as Mayor, finally leading to his defeat at the polls in the November 1972 election.

![]()

![]()

![]()

Density For Whom, and in Whose Interests?

What our beloved city will look like in every neighbourhood, if Vision Vancouver is re-elected

VanRamblings would suggest that there are parallels to be drawn between Tom Campbell’s leadership, and that of Mayor Gregor Robertson, and his majority Vision Vancouver administration.

- Under Vision Vancouver, five blocks on either side of every arterial in the city has been re-zoned for mid-rise building construction, with the potential to upzone to highrise towers across every one of the 23 neighbourhoods that comprise our beloved city. Hell, if you didn’t know better (then, maybe again, you do), you’d almost think that Mayor Gregor Robertson is Tom Campbell reborn with a somewhat more handsome visage, given the “development-at-all-costs” ethos that his Vision Vancouver civic party has initiated and carried through all throughout their development on speed six-year tenure in city government. Tom Campbell would be proud of Gregor Robertson;;

- In the next term of government, with a Vision Vancouver administration in place, the approved multi-tower Oakridge development will pale when compared to the proposed scale of the planned re-development of the Langara Gardens neighbourhood, the area situated between 54th and 57th Avenues, just west of Cambie. And let’s not forget, either, that Gregor Robertson tried to hive off half of the Langara Golf Course for a massive condo tower development, depleting Vancouver’s already diminishing green space (yet another attack on the collective interests of Vancouverites, under Vision Vancouver), attending solely to the pecuniary interests of their development community masters;

- Under a Vision Vancouver administration, our current sitting civic majority party ignored the concerns of neighbours respecting Wall Corp’s out-of-proportion to the neighbourhood redevelopment of Shannon Mews, approving an almost four-fold increase of units (from 200 to 700) in the massively re-developed housing project, proving once again that Vision Vancouver is dedicated to serving the interests of their development masters, with nary a consideration for the livability of our neighbourhoods, whatever area of the city in which we may live;;

- And while we’re on the subject of Wall Corp., do you recall reading, above, of the 860 residents who were displaced when The Raymur Project began construction? Vision Vancouver, too, likes to displace longtime residents from their neighbourhood when they approve development — and, gosh, wouldn’t you know that it’s not social housing that Vision would intend to build when they displace residents, but fancy condominiums to cater to … Take a moment to remind yourself of the controversy surrounding the sale of three tracts of land at 955 East Hastings that displaced 200 longtime, low-income residents — also left to fend for themselves. That’s gentrification under Vision Vancouver, for ya. We’ll write about Wall Corp.’s massive Wall Centre Central Park development at Boundary and Kingsway — another day; that development requires a full column to properly explore;

- Subway. Let’s talk about transportation for a moment. Vision Vancouver wants to build a subway down Broadway. Gee, one wonders why a “subway”, when cities across North America have adopted the low-cost, virtually greenhouse gas free, inexpensive to maintain, neighbourhood-reviving streetcar system? Gosh, it couldn’t have anything to do with the “town centres” that developers would build (and make a fortune on) at each subway station along the route — the city of Vancouver expropriating the four blocks surrounding each station, at Clark, Fraser, Oak, Arbutus, Macdonald, Alma and Blanca streets — all to serve the interests of their developer masters.Patrick Condon, University of British Columbia Chair of Urban Design and Landscape Architecture, likes to refer to this transportation-centred, town centre development style as “gleaming glass towers spread like beads on the string, disconnected from the surrounding communities they overshadow, sentencing neighbourhoods between stations to a future of slowly aging residents, gradually shrinking populations, more empty classrooms, restricted access for young families, fewer commercial services, and an increased dependence on the car to get around”;

- No re-development proposal in Vision Vancouver’s last term was more controversial than the Grandview Woodland development plan, which all but ignored the initial report of the City of Vancouver planner charged to consult with Grandview Woodland residents, and develop a plan the neighbourhood could live with, the report almost completely re-written by staff in the Mayor’s office. Vision Vancouver demanded from the neighbourhood the realization of tower-driven “town centres” at both Clark & Commercial and Broadway, as well as 8+-storey towers along the entire expanse of Nanaimo and Hastings streets;

- In their next term of government, a Vision Vancouver administration would demolish the Georgia and Dunsmuir viaducts, turning over the land beneath the viaducts to large-scale developers, Concord Pacific and Polygon. With the viaducts gone, without saying so in so many words, Vision Vancouver proposes to complete the highway through the east side that many of us fought against more than 40 years ago, driving a six-lane freeway through Strathcona and Trillium parks, as well as two, cherished community gardens;

- And let us not forget, either, that under a Vision Vancouver administration, the Marpole neighbourhood has been transformed as Vancouver’s least expensive, largely rental-driven neighbourhood, to a developer’s paradise of tower-driven condo highrises, mostly catering to a wealthy — and often, offshore — elite.

In 2014, over the course of the past six years, Gregor Robertson has conducted the affairs of City Hall, and the re-development of our city neighbourhoods, as if he is a more contemporary, perhaps somewhat handsomer, yet equally oleaginous, venal, and even more corrupt version of Tom Campbell, objectively, Vancouver’s worst mayor ever.

Come this November 15th, Vancouver voters will face the same question as voters faced in 1972. Do those of us who live in Vancouver want to see continued, untrammeled high-rise development in our neighbourhoods, or do we want livable, sustainable neighbourhoods across our city, where we can raise our families, get to know our neighbours, and preserve the peace and prosperity of the Vancouver that we have all come to know and love?

The choice is yours. Make sure you get out to the polls, 48 days from now.