Recently, VanRamblings received a concerning call at home from an incumbent Vancouver School Board trustee, who told us …

“Raymond, in the years I have served as a trustee on Vancouver’s Board of Education, never have I experienced as dysfunctional a Board as proved to be the case this past term of office. No one was getting along with one another, no one was working in common cause to serve the interests of children enrolled in the Vancouver school system, nor serve the parents of these children. Instead, trustees acted with disparate intent and unfocused attention, at odds with one another on issue after issue after issue.”

The Trustee who made the comments above may well have been talking about this past term on Vancouver City Council, or on Vancouver Park Board.

Whether the enmity on the Board arose from the pandemic, when meetings were held on WebEx, negating the opportunity for trustees to come to know one another, or whether the respective trustees’ intentions for governance of the Vancouver School Board were so politically at odds with one another, the clear message received from the trustee was: change, and a renewed commitment to focusing on serving the interests of students enrolled in Vancouver’s school system is required, as we head to the polls to elect a new Vancouver Board of Education.

Whether it’s the chronic underfunding of public education by an allegedly pro-education New Democratic Party government over in Victoria, or the seeming lack of student advocacy arising from trustee anomie, one thing is very clear: change is needed at Vancouver School Board, along with a re-commitment to democratic engagement with parents who have children enrolled in Vancouver’s school system.

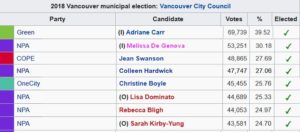

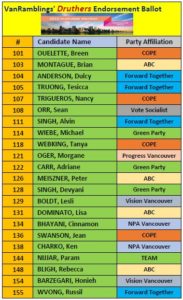

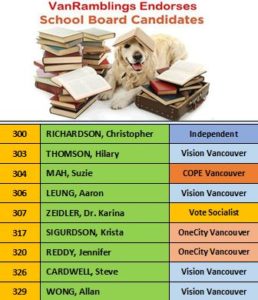

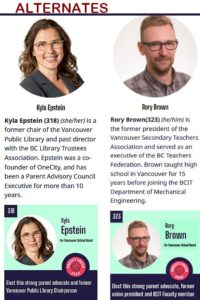

As we would wish at Vancouver City Council and at Vancouver Park Board — as VanRamblings sets about to endorse candidates committed to systemic change, and a reclamation of the role of civic officials to advocate for the citizens who elected them to office, for their families, friends, neighbours and colleagues — VanRamblings today endorses those nine Vancouver School Board candidates running for office in 2022, who we believe will best serve the citizens of Vancouver.

Do you want public education advocates in Vancouver’s school system, trustees who will stand up for children, their parents and you? Then, VOTE for the 9 candidates VanRamblings endorses today.

Those Vancouver Board of Education candidates endorsed by VanRamblings are committed to democratic engagement with parents and students, so as to give parents (and students) a voice in the decision-making around the Board table, and will work to eradicate the systemic racism and intolerance that is an all-too-common and tragic feature of Vancouver’s school system.

- Dr. Karina Zeidler for School Board will ensure the safety of students when the next deadly wave of COVID-19 hits in the late autumn;

- COPE’s Suzie Mah has 35 years experience working within the Vancouver school system and knows exactly what needs to change;

- Jennifer Reddy, prior to being elected to Vancouver’s Board of Education in 2018, completed an MSc in Social Policy and Development from the prestigious London School of Economics, afterwards working from 2010 to 2017 with the Vancouver School Board as an Immigrant Youth & Settlement Worker, supporting youth to stay in school and improve their chances of obtaining meaningful educational or employment opportunities;

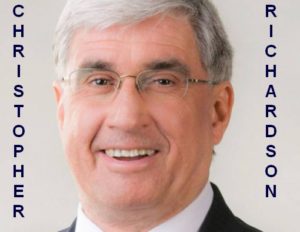

- Christopher Richardson, along with Hilary Thomson for Vancouver School Board and Krista Sigurdson are committed to an inclusive educational environment in the Vancouver school system, that whatever a student’s learning challenges may be, each and EVERY student will be afforded the opportunity for success in the Vancouver school system. Mr. Richardson, since last sitting on the Board, achieved a Bachelor of Education, focusing on the needs of students with learning challenges, at the University of British Columbia, where he is currently completing a Masters degree in the same area of study.

- Given the above, let us not forget either that 23-year Board of Education trustee Allan Wong, education activist Aaron Leung, and former Vancouver School Board Superintendent, Steve Cardwell — all of whom have been working toward getting elected to Vancouver’s Board of Education come this Saturday evening — are skilled education practitioners, not to mention, dedicated public education activists, well deserving of the support of Vancouver voters..

When Vision Vancouver’s Patti Bacchus was first elected as Chairperson of Vancouver’s School Board in 2008, one of her first acts as Chair was to ban citizen engagement during the course of Board of Education meetings. Respectful Board of Education trustee engagement was the order of the day. Most decisions taken by the duly-elected Board of Education are not taken at the Board level — rather, those decisions are taken at the Committee level (there were six Committees of the Board in 2008). Parents, educators, students, Union members, the public and trustees were given free rein to weigh in on the decision-making process at the Committee level, which decisions when made are forwarded to the Board, and almost universally adopted by all nine elected Board of Education trustees.

Not so with the currently elected, and outgoing, Vancouver Board of Education. A decision was taken by the current Board of Education to limit parent input.

Said former Vancouver Board of Education Chairperson Patti Bacchus, in a column published in The Georgia Straight on July 26th, 2022 …

“The current VSB — which talks a lot about equity, access, and transparency — has (adopted) a process that puts tight limits on who can speak at its Committee meetings and for how long (five minutes, maximum, and no more than 45 minutes for all speakers combined), and Committee Chairs have broader powers to decline speaking requests.

Those changes were made in October 2021, in response to a motion from NPA trustees Carmen Cho (who has since been elected board chair) and Oliver Hanson, who cited a desire to ensure that VSB standing committees “function in an efficient and structured way”.

It so happens that Cho and Hansen’s proposed changes — which were presented as a Notice of Motion that would normally be referred to a Committee for discussion and public and stakeholder input — were put to a vote the very night they were introduced, denying the public or stakeholder representatives a chance to weigh in on significant changes that altered decades of VSB practice. Just like that.”

Two notes should be made at this point …

- In June, Board of Education trustees Carmen Cho and Oliver Hanson announced they would not seek a second term as Vancouver Board of Education trustees;

- ALL 9 of the School Board candidates VanRamblings has endorsed today have announced that if they are elected they will vote to restore the previous rules of engagement for parents, students and public, at the Committee level.

The following represents only a few of the commitments the 9 Vancouver Board of Education trustee candidates VanRamblings has endorsed, each trustee candidate has prioritized as work to accomplish upon being elected to office …

- Reinvest in music, drama, dance, art and physical education programmes;

- Prevent the sale of School Board properties to hold these properties in trust in order that they will be preserved for future generations;

- Re-open all school kitchens to build a universal, nutritious lunch programme;

- Expand access to childcare, including full-day care for children under five, and seamless before and after school care programmes on school sites, so every family can find child care at their neighbourhood school;

- Staff fully operational libraries in every school, five days a week;

- Ensure that all school buildings are seismically safe, accessible and well-maintained in the face of climate change and aging infrastructure;

- Provide proper ventilation in all classrooms to protect kids from COVID-19.

As at Vancouver City Hall and Park Board, the presently-elected — and mostly outgoing, given that trustees Cho, Hanson, Fraser Ballantyne, Estrellita Gonzalez and Barb Parrot have chosen not to seek a further term — Board of Education trustees have been captured by staff, have throughout this term been held in sway to staff needs, wants and desires, over setting policy that best serves the interests of those who elected them to office, which is to say, the citizens of Vancouver.

Only OneCity trustee Jennifer Reddy has stood up for the children enrolled in Vancouver’s school system, has advocated for marginalized groups of children of colour, Indigenous children, and children observing varying faiths.

Trustee Jennifer Reddy deserves to be joined by persons of conscience on Vancouver’s Board of Education, which is why we are endorsing a second term for Jennifer Reddy, and advocating for …

Yvette Brend’s story about a racist incident at Lord Byng, on the CBC website …

Suzanne Daley says her 14-year-old mixed-race daughter is still suffering, 18 months after a racist video made by a Lord Byng Secondary School student was circulated at her school.

The Vancouver Police Board is taking a fresh look at how the video incident was handled by police, in the wake of ongoing complaints that no charges were recommended and at least two students felt so unsafe they changed schools.

Markiel Simpson, with the B.C. Community Alliance, saw the video in which a young man, using racial slurs, speaks into the camera, identifying himself and his hatred for Black people.

“I just want to line them all up and just chuck an explosive in there and go ka-boom!”

“We felt an immediate threat. A death threat,” said Daley.

Failure of the current Vancouver Board of Education to Act Against Racism

Only by re-electing Vancouver Board of Education trustee Jennifer Reddy; her OneCity Vancouver colleague, Dr. Krista Sigurdson; Vision Vancouver School Board candidates, former Vancouver School Board Superintendent Steve Cardwell; education activist Aaron Leung; lawyer, a former parent advisory committee (PAC) Chair, parent of four school-aged children, and Board member of Inclusion BC, an organization dedicated to promoting the rights and opportunities of people with intellectual and developmental disabilities, Hilary Thomson; and incumbent Allan Wong; as well as COPE education activist Suzie Mah — a 35-year veteran of British Columbia’s public education system — former activist Vancouver School Board Chairperson, Christopher Richardson; and Vote Socialist candidate for Vancouver School Board, Dr. Karina Zeidler, can Vancouver citizens be assured that each of the fine persons of character on VanRamblings’ endorsement ballot today will ensure action, procedural fairness, and support for the victims of racist violence in Vancouver’s public education system will be promptly and properly addressed.

Here’s a follow-up story in The Tyee, written by Katie Hyslop …

Elise’s friends in Grade 10 at Vancouver’s Lord Byng school were the first to show her the hate video a classmate had made and shared on social media. It was violent, obscene and racist. The student spoke of his desire to kill Black people. Elise (not her real name) immediately reported it to vice-principal Mike Vulgaris, who told her the student would face consequences, she said.

“That goes against what the Constitution stands for,” she recalls Vulgaris saying. Elise believed him. But she still rode the bus home in tears.

That was Nov. 19, 2018. Ten months later, as a new school year begins, Elise is the one who has faced consequences, including harassment and racist bullying by other students. (The reason why we have not used her real name.)

She missed weeks of classes due to fear and stress, and in February she transferred to a different school, abandoning friends and her school community. She had worked hard to get into a specialty program at Lord Byng; that was left behind as well.

The case raises important questions about the response to racism by the school, the Vancouver School Board and police. All failed to take action to ensure the safety of her and other Black students, say Elise and her mother.

Vancouver school trustee Jennifer Reddy said she was aware of other instances of racism in schools across Vancouver, particularly for Indigenous students. She said she’s also heard from school staff members who want the Board to do more to combat racism.

“Staff, who have maybe also seen that video or been subjected to other forms of violence or hate in our community, whether it’s coming from the school or not, are reaching out to say, ‘Hey, is there anything that you can do at the school board level?’” The main thing I can do as a trustee when I hear about things like that is believe students,” she said. “Like when students say, ‘I’m not safe,’ or ‘this happened at my school.’”

Reddy said she didn’t hear about the Lord Byng video until a community activist messaged her three weeks after Elise initially reported it to the vice-principal. She took immediate action because of the confluence of racist incidents she was hearing about in the district, she said. Reddy sent the video to district staff.

But a critical position — the district’s anti-racism mentor — had been eliminated to balance the district’s budget in 2016 after the BC Liberal government fired the school board and appointed Dianne Turner as trustee.

Reddy also tried locating the district’s anti-racism policy. But to her surprise, there was no stand-alone anti-racism policy.

The aftermath for Elise

Around the time when the school district was crafting a statement, Elise and her mother were reaching the end of their rope.

Since their initial meetings, Elise had been repeatedly pulled out of class to attend meetings with administrators about the video, particularly in the first two weeks after it had been discovered. Some meetings were to talk about how she was doing. Others were for things like advising the principal on the wording of his public address announcement about the video.

Despite all the meetings, Elise felt the school never accepted her view that the video threatened the safety of Black students.

“I felt like I was going to school every day getting ready to fight, to fight for what we believed in,” Elise said. Her marks suffered and she lost sleep. Her mother recalls Elise crying almost every morning before going to school.

Parker Johnson, a parent of a Black student at another high school, attended one-on-one meetings to express his concerns over the video and how it was handled. “They did seem interested in hearing my concerns, and open and curious,” Johnson said of his meeting with a district administrator.

Johnson isn’t surprised Elise ended up leaving Lord Byng. He said the district should be reporting on the use of new anti-racism resources, hiring more Black teachers and administrators and pushing for curriculum changes to acknowledge the real histories of racialized people in Canada — including the ownership and abuse of Black and Indigenous people.

Elise, going into Grade 11 next month, is trying to move on from what happened at Lord Byng. The lesson she took away from her attempts to seek justice and safety for Black students isn’t likely the one the district wanted to impart. “The main thing that hurts the most is the reactions to it, telling us we’re overreacting, not taking us seriously,” she said. She needed to leave the school, but it feels like she was the one who lost the struggle.

“I feel like they got a sense of relief. And that’s what I hate about not being there… because I feel like I let them win.”

Vote for an activist contingent of Vancouver Board Education trustees, persons of character and intelligence, who believe in democratic engagement with citizens, who will fight for proper education funding from the provincial government, who will not stand idly by when a racist incident occurs in Vancouver’s school system, who will hold public meetings in the community that give parents and children a voice in Vancouver’s education system, who will fight for you always, with integrity and an unwavering commitment to building the best possible public education system across every neighbourhood in our beloved city of Vancouver.