|

VanRamblings first became aware of the divide between Muslim Arab immigrants and the majority French population seven years ago during a screening of Jeanne and the Perfect Guy when, in the film’s opening scene, the Muslim, Arab and black janitorial staff at a chic Paris travel agency break out into song decrying the exploitative treatment each experiences at the hands of the French, and the pervasive sense of exclusion each feels, their diaspora to France hardly welcome despite the necessity of their labours.

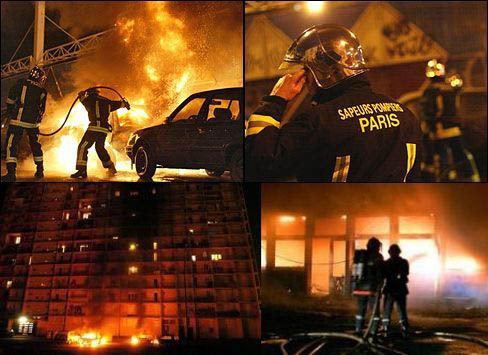

Now, in fall 2005, after almost two weeks of violent clashes between youth and police, as the world looks on in stunned disbelief at the destruction of the social fabric in France, many of us our looking for answers as to why “a tsunami of inchoate youth rebellion” is engulfing France.

As Doug Ireland writes in his piece, Why Is France Burning? The Rebellion of A Lost Generation, “To understand the origins of this profound crisis for France, it is important to step back and remember that the ghettos where festering resentment has now burst into flames were created as a matter of industrial policy by the French state.”

It is the result of thirty years of government neglect: of the failure of the French political classes — of both right and left — to make any serious effort to integrate its Muslim and black populations into the larger French economy and culture; and of the deep-seated, searing, soul-destroying racism that the unemployed and profoundly alienated young of the ghettos face every day of their lives, both from the police, and when trying to find a job or decent housing.

In the course of his essay, Ireland suggests that the events of the past two weeks can be attributed to institutionalized racism and a long, inglorious exploitation of 10% of the population who have consistently been locked out of political decision-making, and denied access to basic education, housing and social services. The history of such treatment of the Muslim, Arab and black population dates back almost a half century.

During the post-World War II boom years of reconstruction and economic expansion, the government recruited labourers and factory and menial workers from France’s foreign colonies. These immigrant workers, primarily from North Africa, were desperately needed to allow the French economy to expand due to the shortage of manpower caused by two World Wars, killing many French men, and slashing native French birth-rates. Moreover, these immigrant workers were favoured by industrial employers as passive, unlikely to strike and cheaper to hire. Literacy, too, was a disqualification, because an Arab worker who could read could educate himself about politics and become more susceptible to organization into a union.

Upon arrival and since, these Arab workers were and are warehoused in huge, high-rise low-income housing ghettos — known as cités (Americans call them ‘the projects’) — specially built and deliberately placed out of sight in the suburbs so that their darker-skinned inhabitants wouldn’t “pollute” the larger metropolitan centres. Now 30, 40, and 50 years old, these high-rise human warehouses in the isolated suburbs are dilapidated, sinister places, housing the hopeless and the alienated, an undereducated, oppressed and rage-filled population of the dispossessed.

Continue reading Paris is Burning: Racism, Poverty and Police Brutality