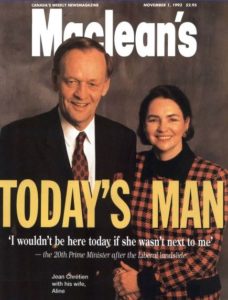

Liberal Prime Ministers Paul Martin and Jean Chrétien, two men who really don’t like one another

In 1990, after having lost two elections to Brian Mulroney, Liberal Party of Canada leader John Turner tendered his resignation, and asked the party to hold a convention to select a new leader.

Five leadership hopefuls entered the race, the most prominent of whom were …

-

- Paul Martin, 51, MP for LaSalle—Émard, Québec since 1988, and Opposition Critic for Treasury Board, Housing, and Urban Affairs; as well as former president and CEO of Canada Steamship Lines;

- Sheila Copps, 37, Member of Parliament for Hamilton East since 1984 and Opposition Critic for the Environment and Social Policy, who from 1981 to 1984 — before entering federal politics — had been a Member of Provincial Parliament in Ontario;

- Jean Chrétien, 56, who had placed second to Turner at the 1984 Liberal leadership convention. As the MP for Saint-Maurice, Québec from — 1963 until 1986 — Mr. Chrétien had served in several senior portfolios under Pierre Elliott Trudeau, including Industry Minister, Finance Minister, Energy Minister, and Justice Minister and was the minister responsible for constitutional negotiations from 1980 to 1982 when the Constitution of Canada was patriated and the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms negotiated and ratified.

During the course of the leadership campaign, Mr. Chrétien and Mr. Martin developed an intense dislike for one another, an enmity that continues to this day.

Mr. Chrétien thought Mr. Martin to be a servant only to the wealthy elite — given Mr. Martin’s family ownership of the behemoth that was Canada Steamship Lines, that Mr. Martin lacked a touch for “the common people”, and that Mr. Martin was unfit for the cut and thrust of federal politics, as well as utterly naïve politically.

On the other hand, while Mr. Martin held great respect for Mr. Chrétien and all he had achieved, his assessment of Mr. Chrétien was no more generous. Mr. Martin thought Mr. Chrétien’s le petit gars de Shawinigan persona to be disingenous, was far too populist, and sensed in Mr. Chretien, an utter lack of a “moral centre.”

The 1990 Liberal Party of Canada leadership election was held on June 23, 1990 in Calgary, Alberta. The party chose former Deputy Prime Minister Jean Chrétien as its new leader, replacing the party’s outgoing leader.

When Jean Chrétien won a massive majority government on Monday, October 25, 1993, when forming Cabinet, Prime Minister Chrétien was quick to appoint Paul Martin as his government’s Finance Minister, assigning him the thankless task of wrestling to the ground the $42 billion annual deficit left to him by former Tory PM Brian Mulroney, and cutting in half the $840 billion accumulated long term debt.

Paul Martin proved an able Finance Minister, and by the time Mr. Chrétien had resigned his office on December 13, 2003, with Paul Martin installed as Canada’s 21st Prime Minister only nine short days later, Jean Chrétien left behind a Liberal corruption legacy that would keep the Liberal Party out of office for 10 long years.

The sponsorship / Sponsorgate / or AdScam scandal, as it came to be known, involved illicit and even illegal activities ostensibly established to counter the actions of the Parti Québécois government intent on achieving Québec independence, with federal monies awarded to Liberal Party-linked ad firms in return for little or no work, in which these firms maintained Liberal organizers or fundraisers on their payrolls or donated back part of the money to the Liberal Party.

Prime Minister Martin was incensed when he learned of the malfeasance of Jean Chrétien, his hated rival, confronting the former Prime Minister …

“Paul, Paul, Paul,” Mr. Chrétien intoned to Prime Minister Martin. “There is only one avenue for you to take. Tell the public that you will order a full investigation of the circumstance that has been brought to your attention. Of course, you’re not really going to conduct an investigation. You’ll do what I did for 10 years: let the public move on from a momentary concern, and continue governing. A failure to do so on your part will mean an early end to your time in office, and a long period of time in the wilderness for the Liberal party.”

Prime Minister Martin’s response to Mr. Chrétien: the establishment of a Commission of Inquiry into the Sponsorship Program and Advertising Activities, headed by Justice John Gomery — which came to be known as “the Gomery Commission.” When reporting out, the Commission found that millions had been awarded in contracts without a proper bidding system, that millions more had been awarded for work that was never done, and that the Financial Administration Act had repeatedly been breached by the government of Jean Chrétien.

The Gomery Commission Report created a firestorm, the scandal featured as a significant factor in the lead-up to the 2006 federal election when, after more than 12 years in power, the Liberals were defeated by the Conservatives — not to return to power in Ottawa for more than 9 years.

Had Prime Minister Martin taken Jean Chrétien’s “advice”, more than likely he would have served many years as Canada’s 21st Prime Minister.

That’s where the hubris comes in.

Hubris derives from the Latin adrogare, meaning one has a right to demand certain attitudes and behaviours from other people. Hubris, it must be observed, generally indicates a loss of contact with reality, and an overestimation of one’s own moral good and capabilities. As such, hubris is often considered to be a fatal, or near fatal, character flaw that can become, if left unchecked, so obsessively all-consuming that it, more often than not, will lead to the complainant’s downfall.

As Prime Minister Martin sought to (rightfully, perhaps) “besmirch” and vilify the legacy of his hated rival — the “villainous and contemptible” Mr. Chrétien — Mr. Martin succeeded only in bringing his time in government to a premature and inglorious end, assigning himself to the scrap heap of history as a “failed leader”, while Jean Chrétien’s multi-term era as Prime Minister continues to be well celebrated through until this day, as a highly revered and universally respected former leader of Canada’s natural governing party, the Liberal Party of Canada.

L-R | People’s Party’s Maxime Bernier, ex-Tory leader Andrew Scheer + current Tory head, Erin O’Toole

L-R | People’s Party’s Maxime Bernier, ex-Tory leader Andrew Scheer + current Tory head, Erin O’Toole

So what does all this have to do with the cost of kombucha at your favourite local grocer, and the current perambulations of #Elxn44?

Think current People’s Party of Canada leader Maxime Bernier, former federal Tory leader Andrew Scheer, and current Conservative Party leader, Erin O’Toole, pictured “left to right” above — which in no way reflects their political positioning.

When, on May 27, 2017, former Speaker of the House and MP for the Saskatchewan riding of Regina—Qu’Appelle, Andrew Scheer, defeated Maxime Bernier — Member of Parliament (MP) for Beauce from 2006 to 2019, and former Minister of Foreign Affairs in the Conservative government of Stephen Harper — with Mr. Scheer becoming the new leader of the Conservative Party, in what was a hotly contested (and, later, a disputed) leadership bid, which at the very last minute saw Mr. Scheer barely defeat his rival by a mere 50.95% to 49.05% margin, bad blood existed between the two rivals from that moment on, causing an excoriated Mr. Bernier to vow that he would seek revenge against a person he found to be wholly inept, and undeserving of the mantle of Leader of Her Majesty’s Loyal Opposition.

In this neck of the woods — way out here on Canada’s west coast, our country’s Pacific playground — we call that kind of revenge … wait for it, wait for it … hubris.

As VanRamblings will express in more detail tomorrow, had Maxime Bernier’s People’s Party not emerged in this election as a rival for the affection of the right wing, libertarian “fringe element” of Erin O’Toole’s Conservative Party — rising as high as 15% in some polls, in Alberta and Ontario, and in the process stealing votes from the Tories — this upcoming Monday, September 20th, Mr. O’Toole would win a majority government, and become Canada’s 24th Prime Minister.

As a play on and reversal of Michelle Obama’s 2016 campaign dictum to aid Hillary Clinton’s Democratic party campaign for President, Maxime Bernier’s campaign theme in 2021 has emerged as: “When they go low, we go even lower.” And, in the process, thwart the ambitions of both Andrew Scheer and Erin O’Toole — leaders of a political party, whose leadership he believes “rightfully belongs” to him.