Anyone who knows me, knows that I live for film, and for the past 37 years have attended the annual Vancouver International Film Festival each spring (in the early years) and autumn since the inception of VIFF in 1981.

For me, VIFF has provided a sense of connection to the larger world around me, and occurs as a humanizing event in my life, helping me to remember that no matter where we live across our planet – be it in Kenya, Kazakhstan, Lebanon, Chile, Italy, Sweden, Vietnam, Guatemala or Iran – the issues we all confront in our daily lives are the same: wont and need, reconciliation with family and the need for understanding, pending environmental collapse, housing as a human right, love, tragedy, personal disaster, rage, injustice and how over time it becomes clearer and clearer how necessary it is that we all work together for change to improve the conditions of our lives, our family’s life and the lives of those around us, to make ours a more inclusive and more socially just world for all, no matter where we live, no matter our ethnicity or sexual orientation, or our economic circumstance, we are all one, and must learn to work together.

The Vancity Theatre … early morning lineups for the early September advance screenings, at 2012’s 31st annual Vancouver International Film Festival (VIFF)

The Vancity Theatre … early morning lineups for the early September advance screenings, at 2012’s 31st annual Vancouver International Film Festival (VIFF)

In the first week of each September dating back to 2005 — when the Vancity Theatre opened — VIFF administrators have held an early morning press conference mid-week at the Vancity Theatre. Some 365 films are introduced, programmers talk excitedly about the films that will be coming to that particular year’s festival, a teaser trailer is shown, Festival Director Alan Franey — if you beg and plead — will provide insight into his favourite films that will screen during the Festival, after which about 120 folks, including actors, directors and producers of Canadian films that will screen at the Festival, repair to the reception area to consume delicious noshing canapés (“hey, we’re indigent writers & actors, it’s our meal for the day!”).

And then the fun really begins …

The very next day — on Thursday — starting at 10am, VIFF commences advance screenings of films where directors, actors and producers for the advance screening films will be present during the Festival. About 30 members of the press, complemented by about 80 festival pass-holders line up outside the Vancity, and after we’ve done our waiting in line, scurry in to find the seats where we’ll remain for the next six hours, losing ourselves in the cinema of the world, the cinema of despair, the cinema of hope.

2012. Noon. Break between films. Vancity Theatre. Sitting in the back row is Len, a Richmond-based filmmaker, and veteran Vancouver Film Festival attendee. As we rise together — I’m sitting in the fourth row from the front of the theatre in the middle of the row, Len is sitting in the back row near the south exit. Except this year for the first time, there is a woman nudging beside him as he stands — would it be fair to say, a beautiful woman, a goddess with an aura around her, an entirely angelic beneficent presence, for she is all of that, a young Botticelli madonna brought to life.

Love, at first sight. Kismet. Magnificent, life-changing, transcendent love.

As I make my way to the south stairway to rise toward Len, looking at me he says, “This is my friend, Julienne. We’re making a film together, a documentary. This is Raymond — he writes about the Festival.”

Julienne is grace in human form, polite verging on deferential. The three of us engage in a repartee, on which subjects I cannot recall.

Julienne looks at me. Clearly, she sees that I cannot move. I am awestruck in her seraphic presence — which I hope against hope she has not sensed, but who am I kidding .. of course she has. But Julienne does not let on, as she sets about to create a protective space, so that my heart will not break.

Each day for the next three weeks, it proves much the same — three, as many as five films screening in advance each day Monday through Thursday, polite conversation between films, talk about the documentary Julienne and Len were making. And I behaved myself — which is unusual for me, because most years I am utterly out of control for the duration of the film festival period, so alive, so lacking in sleep, moved to tears by so many films, in so much despair yet feeling so much hope, falling in love every minute with the women on the screen, with the young, socially gifted women VIFF volunteers — joy verging on madness. But 2012? I was calm.

As is the case with a great many film festival devotees, in the week before the festival is officially to get underway, I create a daily schedule for the 16-day duration of the festival — usually five films, sometimes six or even seven films — that I will see each day, the film schedule based on input from Alan Franey or other festival staff, buzz from film-goers, awards from a dozen other film festivals, and reviews in the New York and Los Angeles Times, Variety, The Hollywood Reporter, Screen Daily, Britain’s The Guardian and The Telegraph, and a retinue of other print & online sources.

My friend, J.B. Shayne, for two decades and more accompanied me to the Vancouver International Film Festival, giving me the nickname, Mr. Know-It-All (J.B. billed himself as Showbiz Shayne). One doesn’t know the meaning of the word insufferable until you’ve encountered me pontificating on one film or other, or what to see that day, or some inside festival scoop, while waiting endlessly in line to gain entrance to one venue or another.

The first day of the 2012 Vancouver International Film Festival, J.B. and I were a little blurry-eyed, lined up outside the Granville 7 cinema waiting to pick up our entrance tickets for the day’s screenings, the first one of which would unspool at 10am. As per usual, in a state of near madness, personalized festival schedule in hand, 100 hundred films lovingly and carefully chosen for both J.B.’s and my viewing pleasure (although we don’t attend all screenings together), me in an excited state of near derangement, dogmatic about the films, “You just must see, take my word for it …” offering my opinion on the work of a particular European director or other, her or his oeuvre and body of work, a crowd gathering around me, present for this early morning devolution into insanity … when …

Julienne, standing in line some ways in front of me, unseen by me, approached. Approached to correct me.

What followed was a professorial treatise on the history of film made ‘live’, and where this particular director fell into the timeline of the history of film and the arts, whose work he was drawing from, the lighting technique innovative and all his own, lambent always with just a touch of sheen, his use of time and space, how he moves the actors around on screen … making it quite plain to everyone standing around that I was but a mere novice on the history of film, a charlatan, an imposter, a pretender, perhaps even a buffoon. And for the first time in 20 years, I was truly in love.

Julienne was angelic in her presentation of information, her love and respect for me infusing her every word of criticism, each word a hug, a kiss, a warm embrace. Here was someone who truly loved me, cared for me, wished to make her presence known and felt, her words a devotion to me, fealty made extant, as real and palpable, as moving and transcendently lovely as anything I have ever experienced in my life, every word uttered by her one of utter respect, and true love and appreciation.

After Julienne completed her discourse on cinematic history, those around us turned away, as it was clear that for Julienne and I there was only the two of us, Julienne and I now standing close, standing side by side, almost touching, Julienne asking to see the schedule of films I had in my right hand. Turning over my personalized VIFF schedule to her, Julienne did the same for me. As she perused my VIFF schedule, I looked at her film schedule — barely recognizing any of the films on her filmgoing agenda, all of the films on my schedule vetted through weeks of painstaking research.

Without hesitation, looking at her list of scheduled VIFF films, I made a decision: for me, this would be the Julienne festival. I threw away my film schedule, knowing that it was essential that I attend at a screening of every film on Julienne’s list. And so it was. We attended every one of her chosen films together, well more than 80 films over the course of sixteen days, never sitting even remotely close to one another at any one of the screenings, for as it is me for me, it is for Julienne: the Vancouver International Film Festival represents the church of cinema …

” … the church and the cinema create a sense of sacred space with their high ceilings, long aisles running the length of the darkened rooms inside, the use of dim lighting, the sweeping curvature of the walls, and the use of curtains to enhance the sacredness of the experience.

The seating, and the opening introduction by a VIFF manager constituting a liturgy for one and all, not dissimilar to the welcoming ritual that occurs in a church service prior to the sermon.

There is, too, the notion that as the film limns your unconscious mind you are being transported, elevated in some meaningful way, left in awe in the presence of a work of film art.

At the Vancouver International Film Festival, there is the vague, unshakable notion that the eternal and invisible world is all around us, transporting us as we sit in rapt attention. We experience the progress and acceleration of time, as we see life begin, progress, and find redemption. All within two hours. The films at the Vancouver International Film Festival constituting much more than entertainment; each film a thoughtful meditation on our place in society and our purpose in life.

Cinema emerging as that place where we might experience life in the form of parable, within a safe and welcoming environment, that place where we are able to become vulnerable and open, hungry to make sense of our lives. Cinema delivers for Julienne and I, as it does for many, access to the new spiritualism, the place where we experience not merely film, but language, memory, art, love, death and, perhaps even, spiritual transcendence.”

And so it went, from early morning til late at night, until one morning while the two of us were in line, a friend came up to Julienne and I, saying …

“What the two of you are doing is disgusting. Raymond, Julienne is 30 years younger than you. She’s a married woman, yet the two of you carry on like you are lovers. Leave her alone. The two of you have no business spending any time together. Stop it. Stop it now!”

Even before Diana finished her denunciation of the two of us, Julienne was crying, tears trickling, then cascading down her cheeks, unable to catch her breath, unable to reply. I wanted to hold Julienne, tell her that all would be fine. But I had not touched Julienne, nor had we or did we intend to have any sort of physical contact, ever. Ours was a love that existed on another plane, our relationship — by which I mean to say, that we related as friends and colleagues, our respect for one another based on an intellectual and spiritual rapport. But physical love? Never would that occur, Never, ever would we together disrespect Julienne’s lovely and generous husband, Bill.

Julienne, finally gathering herself together, her voice catching, was able to utter the words …

“I am so, so sorry, Diana. Raymond and I are friends, that’s all. He has a keen intelligence. I have two PhDs, one in economics and one in medicine. I have taught economics at the Sorbonne, and worked at the Mayo Clinic, yet most days I am unable to keep up with Raymond, his mind is so vibrant, his vast knowledge on the broadest range of academia — save the sciences, where I am wont to point out to him, his knowledge is quite lacking — our rapport entirely intellectual, the joy we experience in one another’s company based solely on an intellectual plane of curiosity, and the desire to learn more, to know more, to be challenged. Somehow the two of us have found one another in time and space, perhaps knowing one another in another life, kismet as Raymond has called it. I would say that is all it is — but all that it is is so great, and so very much appreciated by the two of us that I am taken aback, and profoundly hurt that you would judge me, that you would judge the two of us, that you would think for even one moment that we would ever wish to cause harm, to cause anyone harm. You have referred to Raymond as your friend, in past conversations with me. Diana, a friend does not speak or use the language of judgment you employed in setting about to destroy what is for Raymond and I beauty in our lives, a meeting across the universe.”

And with that, Julienne turned and walked away, the two of us not spending one more moment together for the remaining nine days of the festival.

Then ten minutes following Diana’s denunciation of Julienne, in particular, and me only by association, Diana and her companion, Graham, J.B. and I foregoing the 10am screening found ourselves at the Granville & Smithe Starbucks looking for a coffee, certainly not to calm our jangled nerves, silence between the four us, until we were all seated, me now rising …

“What the fuck did you think you were doing, Diana? You made Julienne cry, Julienne who is as close to an angel on Earth as I have ever encountered. Julienne the personification of loveliness and grace, who would never hurt anyone, nor cause anyone a moment’s concern.

What the fuck were you thinking confronting the two of us on the street? And what business is it of yours, anyway, what I do or don’t do with any person of my acquaintance, particularly when it is as clear to you as it would be to anyone with eyes and a heart, that there is — now was, I fear — a joy that was passing between the two of us, when joy is a commodity in rare possession these days. What in hell would cause you to interfere? Did you, perhaps, think that you were defending Bill’s honour, Bill with whom Julienne and I attend evening screenings together, with me sitting on the other side of the cinema, as per usual, from where Bill and Julienne are sitting. Do you think so little of me, do you think me so lacking in honour and integrity and human compassion, so self-serving and unconscious of the love that Bill and Julienne have for one another that I would, or that Julienne would, engage in behaviour that would be ruinous and contrary to both our natures? Diana — fuck off, never pull that shit around me again. Keep your sick and twisted thoughts to yourself, and never ever speak to me again in the way you did on the street just minutes ago. And one more thing — stay the fuck away from Julienne, don’t ever hurt her again.”

And with that said, I left the Starbucks.

Julienne and I did see one another at the annual Saturday morning, post-festival brunch at The Bellagio, on Hornby at Robson, across from the Vancouver Art Gallery, where 20 or so diehard festival-goes gather each year to debrief on all that has occurred at VIFF over the course of the past month and more, the food and service great, the company — almost everyone present more accomplished than myself, healthy of body and mind and intellect, and inveterate life long lovers of cinema, particularly world cinema — Julienne sitting on the other side and at the end of the table, distant from me. The two of us did not speak. Nor did our eyes meet.

Bill and Julienne and I did get together three more times in the weeks after the festival had ended, for dinner, for a coffee, and for a dessert one late evening. We all got along famously, but it wasn’t too difficult to discern that what had transpired between Julienne and I from early September to early October 2012 could, and would, no longer occur. And, of course, there was the Diana incident. Julienne took a job that required much of her time, and although we communicated from time to time, sometimes in a phone call, more often — but only sporadically — by e-mail, never initiated by me. And then, barely noticing it, the two of us drifted apart … until …

In mid-summer of 2016, I contracted hilar cholangeocarcinoma, a terminal, inoperable form of cancer that was most assuredly going to kill me, sooner than later. Do you recall reading earlier in this story that Julienne had acquired a PhD from the Mayo Clinic?

Turns out that Julienne had trained at the Mayo Clinic under Dr. Gerald Klatskin, best known for his work on the biochemical and biological abnormalities and the clinical features of the diseased liver, but who was also the doctor to first identify and develop a treatment — an operative intervention actually, a rebuilding of the entire bile duct and intestinal system, and replacement of the liver — for hilar cholangeocarcinoma.

Hilar cholangeocarcinoma is often called Klatskin’s tumour, where the bile duct system — a series of tubes or tracts, sometimes called the biliary tract — connects all the elements of the intestinal system to the liver in order that the body’s proteins and materials the body can’t use are eliminated.

Now, I already had a scientist friend — another of the great loves of my life, Alison Fitch, who for the past 10 years has run a multi-billion dollar biotech lab in Seattle, and wouldn’t you know that one of the projects her lab was working on was a cellular intervention to mitigate the growth of cancer cells in the intestinal system, and in the biliary tract and bile duct system, in particular. You wonder why I’m still alive when I was supposed to be dead, at the very latest, a year ago today?

Both Julienne and Alison played key roles in my recovery — one can have great doctors and surgeons, and I did, but it is quite another thing to have women who love you, women who are skilled and are scientists and who love you, who are committed to finding treatments to prolong your life, and working on a “cure”, or at least an intervention that will allow you to live in good health for the next 30 years, while keeping the cancer at bay, women who are on your side, adamant that as long as they’re around, you will be.

In February 2017, when it still appeared that I was a goner — not that Alison or Julienne were going to let that stand — Julienne asked if we might go to lunch at Baguette and Co. on West Broadway, near my home, that she wanted to introduce me to David, whom she and Bill had adopted in Chile, where Julienne was born, and where she and Bill had spent the better part of a year working through the adoption process (why and how it was that Julienne and I had lost contact, she and Bill needing months to help David adjust to his new home in Canada).

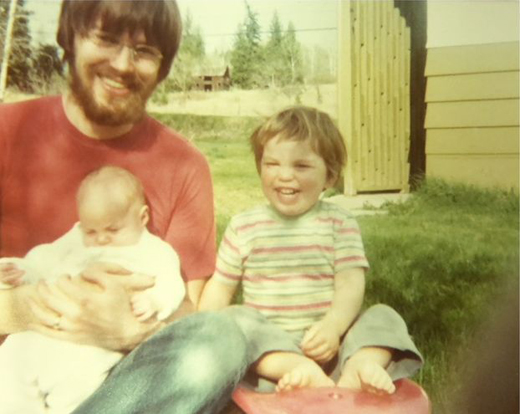

David, 2½ years of age, when we were at lunch together — a lunch that lasted some three hours, Julienne and I having much catching up to do in this leisurely setting — focused only on ourselves and David, with no talk of cancer, but only of joy, a joy that was clearly evident in David’s demeanour, a joy his parents shared with him, David an angel on Earth as much as is the case with his mother, Julienne. Julienne told me that Bill and she had attempted to, and believed they were successful in helping to, create a sense of safety and love for David, that since his arrival in Canada the year previous, he had not cried, nor experienced any emotion other than joy, his life so full of love and goodness and warmth and the love of his parents — to see Bill together with David is to witness the same love that Julienne has for her son, the most hopeful love it has been my privilege to witness.

David’s record of no tears was about to come to a bitter — and, really, there’s no other way of saying it, tragic — end, a part of one of ugliest incidents I have ever been party to, and all arising from an unforgivably heinous, revolting and extremely ugly intervention by my daughter, Megan.

With whom I had spoken at some length over the summer, she telling me, “Dad, I’m raising my sons (my two grandsons, Sasha and Leo) the same way you raised me,” about which she went into some detail, and with then Vancouver School Board trustee Christopher Richardson by my side at the opening of the new General Gordon elementary school — where my two grandsons are enrolled — with Megan, her engineer husband, Maz and Leo nearby, Megan saying my two favourite words, “Hi, daddy,” then putting her arms around me, and then her arm in mine, Maz standing opposite, Leo playing, Christopher standing off to the side, as pleasant and as warm & loving an interaction as any father would wish to have with the daughter he loves with all his heart, who he has known since birth to be the toughest, brightest, most heart-filled person I’ve ever encountered (in all the years I raised her, Megan was the most transcendently lovely and intellectually acute person of whose life I had ever been a part — but tough, omigawd tough, as well as the most socially skilled person I’ve ever known).

When I was diagnosed with hilar cholangeocarcinoma in the late summer of 2016, I spoke with my son, Jude — who was supportive and loving through my months long cancer journey — leaving a message for Megan that I wished to speak with her, calling her mother, Cathy afterwards to ask if she might intervene to mitigate any pain Megan might feel in hearing of my terminal, inoperable cancer diagnosis.

I have yet to write about my cancer journey, and will likely set about to do so once the current Vancouver civic election is over, but for the purposes of this Story of a Life, suffice to say that subsequent to the call I made to Megan in September, and the half dozen or so calls I made to her in succeeding months, when the news about my cancer was getting worse and worse and worse, me needing to hear her voice on voicemail, that Megan had no contact with me, did not as I suggested to her visit with our family physician, Dr. Brad Fritz, or in any other way intervene throughout the eight months I was told my cancer was terminal, my death imminent.

About 2:45pm on that early February afternoon Julienne, David and I were meeting, on this unseasonably warm and sunny February day, after our lunch Julienne asked if I might walk with her and David to Macdonald Street, in order that she and David might catch the bus home. While we were walking up 7th Avenue toward Macdonald, Julienne asked if there was a school nearby, and I said there was, General Gordon, where my grandsons were enrolled. Julienne told me that she and Bill were looking at moving into the neighbourhood, in order to find a good school for David to attend kindergarten — Julienne thought she might drop into the school to speak briefly with the principal, to set up a meeting for a future date.

But that did not happen.

Instead, shortly after 3pm when Julienne, David and I were near to General Gordon school, David spotted the playground and the playground equipment, and ran over to play on the slide and teeter-totter, round-about and other playscape items on the school’s grounds. While David played, a number of kindergarten age and younger children playing nearby, David was full of smiles, as was his mother, the moment one of joy, until …

Megan — my 41-year-old daughter, who I held in my arms for the first 10 minutes of her life, as Cathy was still under anaesthetic, who I raised from the time she was a baby, through her years at UBC — walked up to Julienne and I, her face twisted and unforgiving — something I’d never seen before with Megan, a monstrous look — looking at me, saying in a bare whisper, “I love you,” after which she turned to Julienne, not introducing herself so Julienne had no indication as to who was speaking with her, and said …

“He’s probably told you that he’s going to die. That’s bullshit. He’s only looking for sympathy. Look at him. He looks the same way he always has. There’s nothing wrong with him. You’re being a fool if you believe that there’s anything wrong with him, other than he’s sick in the head …”

At which point David looked over — Julienne’s attention consumed by Megan’s vicious diatribe, Julienne now in tears — a look of alarm on David’s face, a crestfallen look of fear. I immediately went over to David, who was the priority in this circumstance. David wanted his mother.

Megan was still yelling at Julienne, Megan an out of control madwoman, Julienne in response now subject to heaving sobs, David running towards his mother, David now crying, too, inconsolably, both mother and son so emotionally flooded that even in her state of madness, with one adult and one child before her crying in pain, Megan left, yelling some epithet or other at Julienne.

Julienne looked at me, and through tears and sobbing, said, “Raymond, you didn’t say anything.” I took Julienne and David over to sit down, to calm Julienne, David now wailing and inconsolable, David wrapped tightly in Julienne’s arms. I was able to calm Julienne, which took a good five minutes. With Julienne now calm and no longer crying, with David still crying and inconsolable, but quieter now, his face buried in his mother’s chest, I responded to the statement Julienne had made only minutes earlier …

“Julienne, this past six months has brought one piece of tragic news after another. I decided early on that if I was going to live, I would need to establish an equilibrium in my life, and never react to any situation, never give up any control in my life over which I have jurisdiction. If I reacted to all the news I’ve heard on almost a daily basis these past six months, I’d be dead, from fear. I decided a long time ago I would not allow fear to rule my life through my cancer journey, and afterwards should I find myself subject to a miracle. I will not relinquish what little control I have over my life, I will not react, as I did not react this afternoon. If I were to do so, I feel quite assured that I would be sounding the death knell for my life.”

At which point, Julienne — David in her arms, arose saying, “We should go, Raymond. I have to get David home. I’ve got to put some dinner on.”

But it took another 15 minutes to make it the one block to Macdonald, Julienne and David stopping along West 7th Avenue, she concentrating on David’s recovery, his sobs still prominent, his demeanour inconsolable. Finally, David released his tight hold on his mother, putting his feet on the ground, putting one step in front of the other, his body still heaving.

The three of us did make it Macdonald Street, now back in the sun, the time close to 4pm, Julienne now saying that she wanted to walk with David and I over to West 4th Avenue to catch the Macdonald bus — which she did, but not before turning to me, for the first and what would assuredly be the last time, placing her arms around me in an embrace, a tight hug that said, “Raymond, I need assurance that all will be well.”

And then, Julienne and David were gone.

I have told you that I love Julienne. And I do with all my heart — but as I told Bill the next day …

“It seems fated that Julienne and I cannot ever have a relationship. It’s just too dangerous for her. I wish it wasn’t so, because as you know, I love your wife, and there exists between us a rapport of kindness and connection, and an intellectual curiosity that is challenging and rewarding for the two of us. But I will never see Julienne again, nor you or David. I am so very, very sorry for what happened to your wife yesterday. I wish I knew what to say. I simply can’t find the words.”

After walking with Julienne to the bus that tragic afternoon, while slowly making my way home, I called my son to tell him what had happened. Jude was generous, kind and supportive, saying to me by way of explanation …

“That wasn’t Megan speaking today. That was mom speaking. Mom has filled Megan’s head so full of lies and hate, Megan is so conflicted, the entire circumstance of the dysfunction of our lives arising from Cathy’s morbidity, that I don’t know what can be done to repair a family situation so rent that there seems no way of putting the pieces back to make us whole again. I love you. Megan loves you. Maybe some day Megan will get away from Cathy’s influence, maybe some day Megan will make her way back to you in a healthy and whole way — but first she’s going to have to get away from the influence of mom, who will just keep on buying Megan off with trips and the promise of purchasing a new home for her, and as she has always set about to do, buying Megan’s affection, but surely not her love, because although mom is many things, one of those things is certainly not lovable. Forget about what happened today. Concentrate on getting better, or if you’re not going to get better, if your time on this Earth is fated to end soon, then enjoy every day you have left.”

No Julienne in my life, a woman I love. A caring and loving son, though. A conflicted daughter. And, an ex-wife who seemingly wants to destroy me.

And, another story of a life.