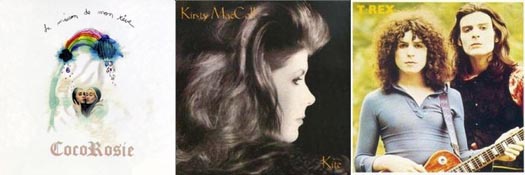

The first of the three love songs on VanRamblings today is sung by an American avant-garde musical group formed in 2003 by sisters Sierra Rose “Rosie” and Bianca Leilani “Coco” Casady, and may be heard on their 2004 album release, La Maison de Mon Rêve.

Having lead a nomadic life, in 2000 after residing in in New York City for two years, Sierra moved into a tiny apartment in the Montmartre district of Paris to pursue a career as an opera singer. Meanwhile, Bianca had moved to Brooklyn in 2002 to study linguistics, sociology, and visual arts. Neither sister had seen one another for a period of ten years.

In early 2003, Bianca made an impromptu visit to Paris to rejoin Sierra, and the two ended up spending months together creating music in Sierra’s bathroom which, according to them, was the most isolated room in the apartment and had the best acoustics, adopting a lo-fi, experimental approach to production, utilizing a distinct vocal style, traditional instruments, and various improvised instruments (like toys), recording with just one microphone and a broken pair of headphones.

By late 2003, the sisters had named themselves CocoRosie and created what would become their début album, La Maison de Mon Rêve, releasing the recording only to friends. However, word got out about the album, and by February 2004 CocoRosie was signed to the independent record label Touch and Go Records, and the album was released on March 9, 2004 to unexpected critical acclaim. The rest, as they say, is history.

The song Good Friday has meaning for me, as I sent it to Lori (who I’ve written about previously), expressing in the note I sent her that the song had particular resonance because it reminded me of her. After not having communicated with one another for almost a decade, posting the following song to Lori caused the two of us to, briefly, rekindle our relationship.

If 1988, the year I met Lori, was one of the great years of my life, the next great year in my life was 1995, and the summer of the gregarious 22-year-old Australian twins Julienne and Melissa, now all nicely married with great husbands, and two children apiece. That the three of us still communicate today I consider to be one of the great achievements of my life. I love them as much now as I did 25 years ago — both women (who I will write about someday, but employing pseudonyms) hold a special place in my heart.

1995 was also the year that my friend J.B. Shayne introduced me to the music of British singer-songwriter Kirsty McColl, whose 1989 album Kite became the soundtrack of my life that particularly warm and loving summer. I remember alighting from the #9 bus at Macdonald and West Broadway, as Julienne and Melissa were rounding the corner onto West Broadway, having just come from the Kitsilano library.

Spotting me, the two ran down the street towards me, jumping into my arms and wrapping themselves around me — the same thing happened later that summer, when I had just entered the west entrance of the Macdonald and Broadway Safeway, with Justine Davidson — then all of 15 years of age, and someone to whom I’d been close, and in whose life I had played a fatherly role for years — having entered from the east entrance, upon spotting me ran across the Safeway, jumping into my arms, wrapping herself around me, clearly happy to see me. There is no other time in my life when I felt more loved than was the case in the summer of 1995.

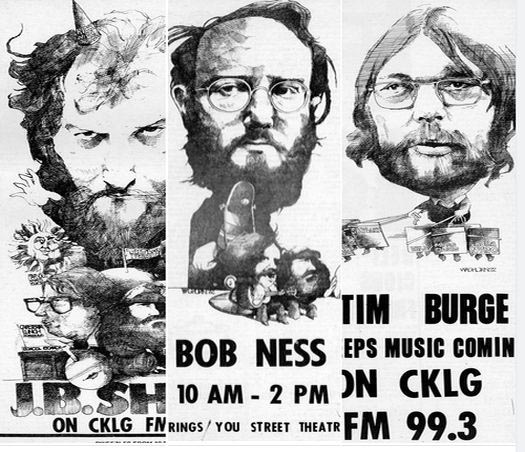

I was first introduced to the music of T. Rex (initially known as Tyrannosaurus Rex), the English rock band formed in 1967 by singer-songwriter and guitarist Marc Bolan, when working at LG-FM, by Bob Ness, one of the great all time radio announcers in Vancouver, and more than anyone else of my memory, the father of alternative music radio in Vancouver, when he brought the music of Marc Bolan to my attention.

By the early 1970s, I was a student up on the hill at Simon Fraser University, and arts and entertainment editor at the student newspaper, The Peak — where among my myriad endeavours, I was afforded the opportunity to review five albums a week, one of which was, in early 1971, T. Rex’s eponymous fifth album, and the first under the name T. Rex.

If you haven’t guessed, I am a romantic, always have been, always will be. For me, there is no greater joy than being in love — in which respect I have been very lucky, in platonic and other kinds of love (and even a marriage) with incredibly bright and empathetic women, who are responsible for all the best parts of who I am, and how I have brought myself to the world.

My first great love, of course (and the mother of my children) was Cathy Janie McLean, a striking 18-year-old blonde Amazon of a woman, possessed of a keen intelligence, and the woman more than any other who shaped me, in the early years loved me, and created the somewhat sophisticated wordsmith and bon vivant I’ve been for nigh on 50 years now.

T. Rex’s song Diamond Meadows was a song that was particularly resonant in Cathy’s and my life, a song we returned to for years, when I was at university, and later teaching in the Interior. For me, listening to Diamond Meadows reminds me of a time when I was truly loved, when everything was going well in my life, when I was surrounded by friends, politically and socially active, and a young man of promise and capable of much good.