On a chilly Tuesday, February 9th afternoon in 1989, I was fired from my job as a teacher at a privately-operated school for gifted children.

The principal at the school had met with the parents of one of the students in my class, a nine-year-boy, the boy’s parents instructing the principal that they wanted their son promoted from Grade 4 — the grade he was in — to Grade 7, a request the principal readily acquiesced to. After all, hers was a business bent on lining her pocket and making her rich, not education and the welfare of children, so why wouldn’t she accede to such a request?

Towards the end of lunch hour that overcast day, the principal called me into her office, and instructed that, going forward, I was to teach this young boy from materials provided for the two Grade 7 students in my 15-student classroom, explaining why I must do this, and her expectation that I would immediately act on her demand.

Unsurprisingly, for anyone who knows me, I refused her untoward request.

The boy in question had experienced problems with the Grade 4 curriculum, could barely read, with arithmetic and math skills more common for a late Grade One student. I told the principal that as the boy was already struggling with academic work appropriate for the Grade 4 level, I could not in all good conscience — and as a professional & given my obligation to the young student — would not, in the circumstance, accede to her demand.

The principal, now sitting rigidly in her chair, looking directly at me with steely eyes, asked me the following question, “What difference does it make whether the boy is working with the Grade 4 or the Grade 7 curriculum, they’re virtually the same? What difference does it make to you whether he’s working with Grade 7 or Grade 4 textbooks and curriculum? Make no mistake, Raymond: I am not making a request of you, nor a demand. As the principal of this school, I am ordering you this afternoon to move (student’s name) work to Grade 7. I hope I am making perfectly clear what is expected of you, by me, as the principal, and owner, of this school.”

At which point, I re-iterated my concerns to the principal, once again letting her know that I could not, and I would not, move the student into Grade 7.

With a cold look of disdain on her face, the principal, with a meanness I had not seen previously, in a quiet and measured tone, said, “You’re fired. I will make arrangements this afternoon to have your belongings delivered to your home. Leave the school immediately. You are no longer in the employ of (name of school), nor will you speak of why you have left to anyone.

The events that lead up to my dismissal from the school, the impact my firing had on the parents, and more particularly on the students in my class, who were devoted to me, is a story for another day, a story I am not yet brave enough to tell. Perhaps someday. Not today.

Although the headline for today’s story reads “Aftermath of Being Fired”, my use of that particular description is, for the purposes of today’s story, meant to apply only to the events of that particular Tuesday, February 9th afternoon, and not the years’ long aftermath of my employment termination, which story, as I write above, I may write another day.

Little white house: 336 East 28th Avenue, in the Riley Park neighbourhood of Vancouver, the home of my father, John Tomlin, in the 1980s and 1990s

Little white house: 336 East 28th Avenue, in the Riley Park neighbourhood of Vancouver, the home of my father, John Tomlin, in the 1980s and 1990s

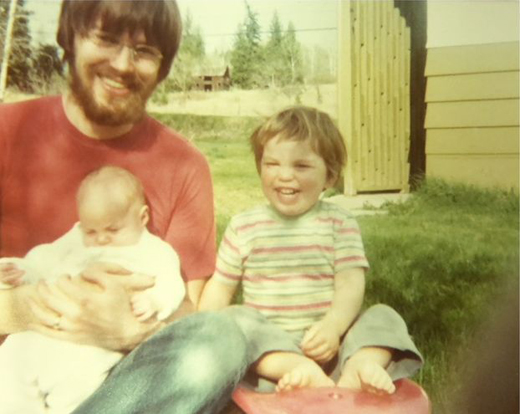

Today, I have another story from my life that occurred in the aftermath of my firing, on that chill Tuesday afternoon, when I drove to my father’s home on East 28th Avenue near Main, where warming cups of tea awaited me, and where a story that I will always cherish unfolded that afternoon, the story I am about to tell you, that to some great extent has provided the impetus and rationale for the weekly VanRamblings’ Stories of a Life feature, as a gift for my two children, in order that they — along with you — might know me better, the stories to be found by clicking on the stories of a life rectangular box, among the highlighted links at the top of the site.

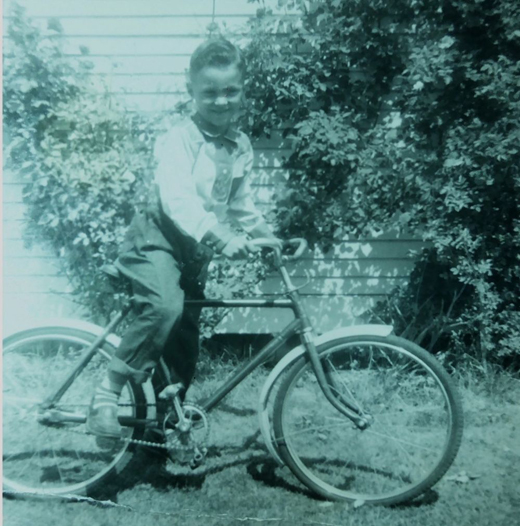

</ br>My father, John Tomlin, outside our home on Venables Street, circa 1962

</ br>My father, John Tomlin, outside our home on Venables Street, circa 1962

As is my usual custom after an upsetting event, I got into my car and drove around town, lonely and wandering down the streets and around the city, arriving at my father’s home on East 28th, about 2:20pm that afternoon.

I knocked on the door, my father invited me in, put on some tea, and we sat down at the kitchen table, as per our usual custom. He didn’t ask what I was doing over at his home in the middle of the afternoon, and why I wasn’t at work. He was at home alone, we were in his home alone together, his second wife, Rose, at work. That afternoon it was just the two of us.

With the sounds of country music wafting in the air from CJJC radio Langley, as we sat there and drank our tea, my father now having put some biscuits on the table for the two of us to eat, I didn’t tell him of the events of earlier that day. I was feeling in a pensive mood, quieter than usual, reflective, when an idea struck me.

Here we were, just the two of us, no one expected home until at least 6pm, quiet in the house except for the plaintive sounds of country radio in the background, and I thought to myself, “Well, Raymond, it’s now or never. Ask Dad about his life. Tell him that your curious. Ask him if he would tell you about himself, and his experience of life.” So, I asked my father. He put his hand to his chin, looked down, and began …

“As you know, I was born on the prairies in the autumn of 1916, in northern Saskatchewan, one of six boys and girls, all of us working the farm from the earliest age. My father died when I was three, and given that I was the second to oldest, it was my job to take care of my younger twin brothers and twin sisters, and my older brother, too, to care for the farm, and care for my mother. It was a hardscrabble life for me from the age of six on — we struggled, often there wasn’t any food on the table, and we went days without anything more than a bit of bread and butter.

I was in Grade One at the age of six, but I had to quit because I was needed on the farm.

Life up until the end of the 1920s stayed much the same, the only relief we had from the sameness of our days, was our old Marconi radio, which had been a gift from one of our neighbours who had decided to move away, leaving his possessions behind, as he went off to look for work, and a life better than what he, or we had in our struggling farm community.

Then the Great Depression hit, and we had to go on Relief, the bottom fell out of the market for wheat, which was our main crop, people packed up and left for the city to see if they could find work, and for those who were left behind, it was devastation, Dust Bowl like conditions, with not enough coming in to keep kith and kin together. By 1930, the only option available to me became clear: like thousands of others, I would ride the rails, looking for work and looking for a handout if I was going to survive. Staying at home, all I’d be was a burden. So, I packed up an old kit bag, went down to the railyards & jumped into the first open car I could see, the surprise of my life confronting me once I was onboard, when I looked around, i saw another 20 guys, looking gaunt and worn out like me.

And that was my life throughout the Great Depression, riding the rails from one end of Canada to the other, picking up work wherever I could, spending time each summer in the Annapolis Valley picking apples, eating as much as I could to fill my belly, working long days, living in hobo camps at night — we weren’t tramps or bums, we worked for what we got — learning to cook chicken and flat bread over the camp fire. All and all, I thought we did pretty well, but near 10 years of that life, and I was ready for a change, ready to settle down somewhere. But the economy wasn’t getting any better, I couldn’t read and my prospects were poor.

In early September of 1939, I was living in a hobo camp on the outskirts of Revelstoke, on my way to the Okanagan to pick apples. There was talk in the camp that something was up in Europe, that the German Army had invaded Poland. On September 10th, I was in town looking for food out back of a restaurant when I heard a bunch of kids, saw them running down the street, screaming into the air, “We’re going to war. There’s a war. We’re going to fight those dirty …”

Next thing I knew, there was a hand on my shoulder, a man in a uniform. “Son,” he said to me, “we’re at war now, saw it comin’. I’m with the Army recruitment office just down the street. Why don’t you come with me, and we’ll get you signed up. Three squares a day, a nice clean uniform, and you’ll get to see the world. No more living in hobo camps for you.”

So, I did, I went with him, signed up. For the first time in almost a decade, things were looking up. After I signed my name on the dotted line, the sergeant handed me an army uniform, saying, “Find a place to put this on.” I ran back to the hobo camp, more excited than I’d been in I don’t know how long. There was a pond nearby the camp, I stripped off my tattered old clothes, jumped in the pond, got myself nice and wet, dried myself with my old clothes, and set about to get dressed up in my spanking new uniform. I don’t think I’d ever felt better in my whole life.”

At which point, my father got up from the table when he heard a knock at the front door. It was a neighbour asking my father if he could borrow one of my father’s tools. My father went downstairs into the basement, retrieved the tool and gave it to his neighbour. After pouring us both a cup of tea, and replenishing the biscuit tray, my father returned to the kitchen table, and began the telling of his story once again.

There were small barracks in Revelstoke, but we weren’t going to be there for long. Canada knew that a war was coming, preparation had been made, and within two days we boarded a train – not a boxcar, but a real train car with seats, and a dining room car, as we headed towards Saskatchewan for six weeks of boot camp, after which we were told we’d be shipped to London. Boot camp went by in a blur. I was tough and strong, as I’ve been all my life, and boot camp was fine, the 600 or so of us in the camp boarding a train for Halifax, a ship waiting for us to take us to London.

Upon arriving in England, we stuffed our belongings away, all 600 of us now resident in the major garrison for Canadian solidiers, our barracks in Aldershot, in the Rushmoor district of Hampshire, England, along the southern coast of the country. All looked well until I got sick about a week in, and was hospitalized with some sort of intestinal disorder, some form of hyperthyroidism, I think, causing a massive weight loss for me, until I was little more than skin and bone. Which is when and where my osteoporosis first presented itself.

Soon enough, it became clear that I wouldn’t be seeing any action on the front. One of my lieutenants assigned me to the stores, the supply centre for the camp, which is where I spent the next three years of my life. It wasn’t bad over there, I made friends, worked hard, went to dances on the weekends, did a bit of volunteering and thought that, all and all, it wasn’t a bad life.

But I got in with a bad lot. There was money to be made working in the stores, with a big black market for all sorts of goods that we kept in the supply warehouse at the garrison. A few of the hustlers in the camp, soldiers who had also gotten a deferment for some other phony malady or other, ended up as a group taking over the camp’s stores, and ran a racket out of there you wouldn’t believe. I’ve always been a ‘go along to get along’ kind of guy, but what I saw worried me. Still, there wasn’t much I could do. It wasn’t as if I was going to go to the commander and rat these guys out.

Next thing I knew, I was in hot and heavy in all the schemes dreamed up by these creeps, who were inventive in how they could rip off the camp, curry favour with the girls in town, making a killing through sales of tens of thousands of dollars, and more over a period of time, of Canadian army goods. I knew it couldn’t last, and it didn’t. One morning I was rousted out of bed by the MPs, and taken to the brig to await trial on charges of theft and conversion and what not. I served most of the last two years of the war in the brig.”

When the war came to an end in May 1945, my father told me, almost the entire camp went into London to celebrate V-E Day. “It was quite a day, let me tell you,” he said, almost wistfully.

Soldiers and friends celebrating V-E Day on the streets of London, May 9th 1945

At this point he realized he hadn’t had a cigarette all afternoon, and told me, “I’m going out back for a cigarette. You can stay in here for awhile. I need some time to myself.” Moving slowly, he left the house.

When my father came back into the house and returned to the kitchen, pouring himself a fresh cup of tea, he sat down once again at the kitchen table, asking me, “Do you want to hear anymore?”

Yes, oh yes, oh yes, please God, let this story of a life continue — but all I said was, “Sure, I’d like to hear more. Can I ask you a question, though? How did you meet mom?”

“Once the war was over — surprising to me, I got an honourable discharge — it was only six weeks before I found myself on board a ship headed for Canada, but not Halifax this time, because the port was too small to handle the tens, the hundreds of thousands of returning troops. No, the ship I boarded was to travel through the Panama Canal towards our destination of Vancouver, British Columbia.

Arriving in Vancouver, I was able to find a small room in a boarding house — there were lots of those that cropped up to house returning soldiers like me — and set about looking for work. Fun was to be had on the weekends, at dances mostly, which is where I met your mother. Man oh man, could she dance. Your mother really liked to have a good time. She was kind of a pretty young thing, too, eight years my junior. We got to dancing one evening when she told me that I was “the one”.

“The one?” I asked, to which she replied, “Yes, you’re the one I’m going to marry.” I suppose I was kind of handsome in those days, with a kind of rugged if gaunt look, a three day growth wiry beard most days. Your mother’s proposal got me thinking. That night, your mother and I became an item. She was working, slinging hash at some diner or other, while I was still looking for work, living off the re-establishment veterans benefit that the Canadian government paid us. It wasn’t much, but it was enough to get by on.

Things went on like that throughout the summer, and into the early fall, and your mother was always on me to set a date. But you know me. I have an impossible time making up my mind about almost anything. One morning your mother came to my rooming house, told the landlady she wanted to see me, and marched right upstairs to my room, busting through the door like a force of nature, which you and I know she always was and continues to be, I imagine. Your mother confronted me, saying, “I’ve waited long enough. You’ve got to make up your mind. I want to be married by the end of the week, if not sooner. Either we get married now, or it’s finished, we’re over.”

I hemmed and hawed. I just didn’t know if I wanted to get married. And your mother, she was a piece of work, not often easy to get along with, demanding, opinionated, loud and like I said, a force of nature. I thought to myself, “Mary is too much woman for me. What would my life with her be like?” Not bliss, I knew, but something, although I wasn’t sure what.

Your mother, looking me right in the eye, said, “I’ve got a job waiting for me in Drumheller. I’m going down to the CN station on Main Street, and I’m catching the 5 o’ clock. Once I’m on that train, you’ll never see me again.” And then she stomped out, slamming the door behind her.

I just sat there. I thought to myself, “You know, Jack, you’re almost 30 years of age. When are you going to get married? When are you ever going to find another girl?” And I just lay there, thinking and thinking and thinking. I didn’t know what to do. I got on the bus, headed downtown, and walked to Stanley Park from there, because I needed some quiet, and some time to think.

Finally, by around 3pm, I’d decided. For better, or for worse, I’d marry your mother. I got on the bus, and headed in the direction of the CN station. When I arrived at the station, I walked through the big front doors, and found that the place was packed. Even so, I spotted your mother, who was in line getting ready to board the train. I ran up to her and said, “Will you marry me?” And with that, this petite 21-year-old girl jumped into my arms, and said, “Yes, a million times yes.”

I moved out of the rooming house, and your mother and I found a basement suite up by Fraser and 57th. By year’s end, your mother was pregnant with your brother Robert. Oh, I forgot, no one’s ever told you that you had an older brother. He was born in the summer of 1946, but was kind of sickly. Within three months he was gone.

Your mother was so sad that she told me she needed to be near family if she was going to get through the loss of your brother. So, we packed up, and a few days later, we were on our way to Drumheller, Alberta, and that job your mother had been promised, where she had friends and work, and a place where she could recover, not that she ever did, I don’t think.”

And with that, my father got up, gave me a hug, and said, “You better be on your way. I think I’m going to pick Rose up from work today.”

“I love you son.”

And thus ends the saga of my father’s life, in the years before I was born, a story that was mine to cherish — for the rest of my life. It is the telling of that story that has led to Stories of a Life on VanRamblings.

I have often thought to myself, “Fire me any day of the week, and twice on Sunday, if the result is a story like the one my father told me that day.”

And so it is, and so it always will be. A gift of deliverance as told through narrative, my history laid bare through the words my father spoke to me that afternoon, and a life lived that much better and with more meaning, in the knowledge of where I’ve come from — although the details of that story, the story of my young life beyond, is best left for another day.