In November 2017, I wrote of a signal event of my life — a 7th birthday present from my mother of a transistor radio, on August 11th, 1957.

The acquisition of the leather-encased transistor radio — I was the first boy in my neighbourhood to own one — so influenced my life that I developed not only a lifelong love of pop culture as a consequence of receiving the present, but a lifelong love for radio, which less than 10 years later would see me working at CFUN — then Vancouver’s rock ‘n roll giant — studying with Red Robinson (at the time, the programme director), producing the station’s Sunday night programming, and occasionally going on the air.

The gift of the transistor radio also meant that after going to bed at my usual bedtime of 8pm, I could turn the radio on to CKNW and listen to the classic radio programmes of the 1940s and 1950s: The Shadow, Our Miss Brooks, the Jack Benny – a favourite – and Red Skelton shows, and George Burns and Gracie Allen, and The Charlie McCarthy shows.

Summer 1957 also had a darker aspect.

For the first five years of my life, I didn’t speak. I sang, but I didn’t speak. Early childhood trauma, I expect — neglect, a lack of love, and darker goings on I won’t write about today, but there was joy in my young life — the Sunshine Bread truck that would situate itself in the park at the end of Alice Street, over by Victoria and 24th, providing the young children who lived in the neighbourhood an opportunity to ride on the tiny merry-go-round on the back of the truck, the children running home to their mothers saying, “Mom, oh mom, you’ve got to buy some Sunshine Bread.”

During this period, though, and throughout my life, there was not a mother at home for me to run to. My father, too, was absent; I’m not sure where he spent his days, all I knew was that he didn’t have work — my parents argued about it all the time — and neither was he a fit parent, as he proved time and time again. There were nannies at home, recent immigrants from Germany, mostly, from whom I acquired my love of warm & filling oatmeal for my breakfast in the morning, for there wasn’t much food in my home, and often that oatmeal breakfast would constitute my meal for the day.

At age five, I began to speak, first haltingly and then in full sentences. For anyone who knows me, they’d probably say that for many years now, I have been making up for the lost words of the first five years of my life.

In my home, there were no bedtime stories. Not that either of my parents were inclined to read to my sister and I. My father had a Grade One education, and couldn’t read. My mother had a Grade Three education, and she could read — but not to either me or my sister. Not that she was ever around the house long enough to read stories to us, even if she was so inclined — which she wasn’t.

My mother was the breadwinner in my family.

From the earliest years of my life, through all the years of my maturational growth, my mother always worked three jobs — for many years she worked days at Bonor and Bemis, just off Strathcona Park, a factory job where she worked in the part of the factory responsible for making paper bags; afternoons saw my father lifting my sister into the back seat of the car to pick my mother up from work, to drive her to Lulu Island and the Swift Meat Packing Plant, after which my father, sister and I traveled home in our 10-year-old Plymouth, the car barreling down Victoria Drive, with my sister far too often opening the back door of the car, spilling out onto the roadway, as my father’s car sped away down the street, me screaming, “Dad, dad — Linda’s jumped out of the car!” at which point he would stop, turn the car around and head back to where my sister lay in the middle of the road, a car having stopped so he wouldn’t run her over, holding up traffic, my father rushing over to pick up my sister to take her home.

In any one of those incidents, my father never thought to take Linda to the hospital. Sometimes the driver of the car that had stopped — to prevent himself from driving over Linda — would repair to my home, on Alice Street, or East 2nd Avenue, with me screaming at my father or the man or men who were standing around in the kitchen of my house, Linda laying bruised and bleeding on the hard melamite kitchen table, me now screeching at the adults gathered around my sister, men hands held to their chin, doing nothing, my screaming at them to take her to the hospital.

But they never did.

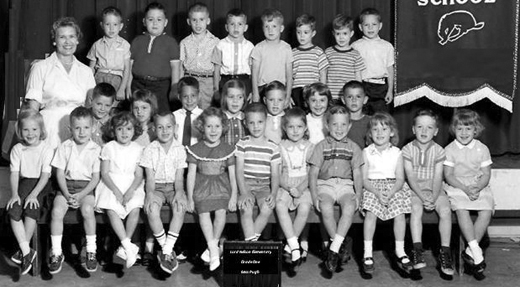

In September 1956, I entered Grade One. My mother was actually present to enroll me my first day of school at Lord Nelson Elementary, at Templeton Drive and Charles. Miss Pugh was my Grade One teacher. The only memory I have of her involves asking the children in class to put our heads down on our desks when her boyfriend would come to visit, as I peeked toward the front of the class, where I would see the two of them kissing — the only affection between adults I had ever witnessed to that point in my life.

Grade One was, for me, a blur.

I was, I suppose, unmanageable, full of life, although I don’t have any strong memories of my attendance at Lord Nelson Elementary school, from September 1956 through June of 1957 — I had never been socialized, no one had ever made demands of me in regards of my conduct, although I would receive hard spankings if I got out of line, although it was always difficult to determine what “getting out of line meant,” as there were no boundaries around my conduct that I can recall having been set for me.

I enjoyed my pre-school days (read: before I attended elementary school), and I suppose I enjoyed school, my memory of playing marbles at recess acute. Quite honestly, though, I can’t remember anything else of my first year of school — apart from the kissing at the front of the class, from time to time, between my teacher and her boyfriend. As my mother was working three jobs — 16 hours a day, six days a week, 24 hours on the 7th day, the unskilled factory jobs paying, early on, about 25 cents an hour, climbing to 35 cents by 1957 — I was lost, there were no governors in my life, no love, no affection, I felt alone, and more often than not, full of dread and fear.

My most cogent memories of September 1956 to June 1957 are this …

- Walking to school alone through billowy white fog, so thick you couldn’t see your hand in front of you, arriving at school on time, and settling into a day where I would learn nothing;

- Running to Joy and Louise’s house after school, and playing with them for 2 hours, their parents at work, just the three of us at home playing make believe;

- Spending occasional afternoons at my best friend John Pavich’s home, his mother with fresh-baked, warm cookies at the ready, a glass of milk on the table. I would often stay for only a half hour, after which I would walk down Charles Street in the rain, towards Nanaimo, rumbling thunder and lightning in the steel blue skies a wondrous delight for me.

I have always felt most secure in overcast weather. Clouds in the sky, particularly the dark billowy clouds that covered the sky on those most overcast of days, offered me a secure and reassuring blanket, a security I lacked in every other aspect of my life, my love of darkened — some would say, forboding, but not me — a feeling that lives in me still.

I love the rain, I love leaden skies, I love the security that those overhead clouds continue to provide me, as if nothing bad can or will happen to me — and in a life, as far back as my pre-school days, an ever more present and necessary feeling as I glided through my Grade One year, untouched, unaware, when I raised myself alone (who knew where my sister was?), the clouds in the sky offering me the only security that was available to me.

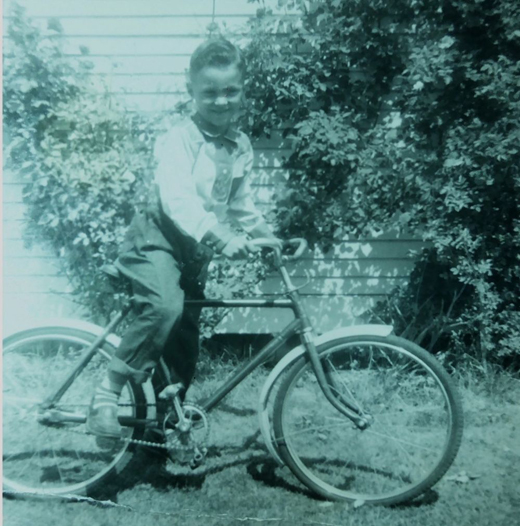

Six-year-old me, Raymond Tomlin, on my bike, outside my home, in the spring of 1957

Six-year-old me, Raymond Tomlin, on my bike, outside my home, in the spring of 1957

As the school year was ending, the sports day complete, the warm summer days having now just begun, on the last day of school in June 1957, I received my report card, taking it directly to my home as instructed by my Principal and my teacher. There was no one home. I played make believe all on my own. I left my report card on the kitchen table. Alone, I felt fatigued, and went to bed early on that June 30th afternoon, unsure of what the summer would bring, and what life held in store for me.

Early the next morning, following 12 hours of fitful sleep, upon opening my eyes, I was surprised to see my mother standing over my bed. She looked at me, seething, her lips pursed and tight, her face purple with rage — next thing I knew, she hit me across the face, hard. “You failed Grade One. No son of mine is going to fail Grade One. You are in for a summer of hell!”

And so it proved to be.

For the only time in all the years I lived at home, my mother left her employment, staying home with me through July and August, the renters in the downstairs suite evicted that summer, my days of hell beginning at 8am, tied to a chair in the kitchen of the downstairs suite, from 8am til 8pm Monday through Friday of each week of summer 1957, for near on 60 days — save my birthday, on August 11th, when I was given a day off — I was beaten, the rope tying me to the chair cutting into my skin, the early part of the summer finding me screaming in fear and in pain.

Hour upon hour upon hour.

Of course, in those days, there was no definiing concept of child abuse, no such thing as a Ministry of Human Resources or Ministry of Children and Family Development, no one to look after the welfare of children. A child screaming, most parents — at least in my east side Grandview-Woodland neighbourhood — thought the child probably had it coming to them.

Over the course of the thirty-one days of July 1957, something of a miracle occurred amidst the tears, and the now lessening screams of the day: I learned to read. I learned arithmetic. I learned to print. I learned everything I had not learned in ten months of enrollment in Grade One.

By summer’s end — as would soon be discovered, I knew how to print and to write in cursive longhand, my arithmetic skills progressing far beyond basic addition and subtraction into fractions, and elementary algebra and geometry. I learned to read, I read for hours every day.

I memorized the small dictionary my mother had purchased for the express purpose of teaching me language. I learned the meaning of thousands of words, and I learned to spell those words correctly — lest I be beaten, or slapped hard across the face. That summer I learned to love learning.

On the first day of school in September 1957, my mother — as you may have gathered, a force of nature — marched me into the school office, confronting the Principal, an anger in her that had transmogrified into rage, my mother fierce and unrelenting in a barrage of hate-filled words that filled the room, fear and dread also filling the room, the Principal clearly unsettled, teachers running towards the office to see what this mad woman who had taken control of the office wanted, was demanding.

“My son is ready for Grade 2,” my mother screamed at my Principal, whose complexion now was ruddy, his face shuddering, his eyes wary, wide, concern – perhaps for his safety, perhaps for me – spilling out of his eyes.

“But Mrs. Tomlin, your son can’t read, he doesn’t even know the letters of the alphabet, and he doesn’t know how to do even the most basic addition and subtraction, not even one plus one equals two. I cannot place your son in Grade Two, just because you wish it to be so.”

My mother looked around the office. There was a large plaque on one of the walls, with 20 or so lines of print on the plaque.

Turning to me, pointing to the plaque, she bellowed, “Read it.” And I did. While I was reading the dozens of words on the plaque, my mother looked around the office, spotting a Grade 5 Math book.

Handing the Math book to the Principal, her eyes now in a squint, she demanded of the Principal, “turn to any page, ask him to solve any problem on that page. Now!” The principal did as he was instructed to do by my mother, asking me one question after another, as he flipped through page after page of the Math book. I answered every question correctly — and quickly, as I had been instructed in my basement dungeon at home.

The Principal turned to me and said, “Wait here son, take a seat over there. Mrs. Tomlin, please come with me to my office.”

Twenty minutes later I entered Mrs. Goloff’s Grade Two class, in a portable outside along Charles Street, beginning what would be one of the best years of my life. The school had spelling bees. I won every time, not just for Grade 2, but for the whole school. I breezed through Grade 2. Somehow, over the summer, I had gained a love of learning that resides in me still, and informs my life each and every day. I loved to read, spending hours in the school library reading whatever I could get my hands on.

I loved challenging myself, my facility with math always not just functional, but acute. And memory — looking back on it, I suppose the summer of 1957 was when I acquired my near photographic memory. I loved challenging myself to remember facts and information, discovering a way to achieve near perfect recall by inventing context through narrative. I suppose, too, that the summer of 1957 was when I first gained my love for narrative — as a tool and as a means to create recall and meaning, and a feature of how I would bring myself to the world, from my years in radio having to memorize how long the “musical beds” were for hundreds of songs, so that I could speak over the musical beds right up to the beat just before the lyrics to the song would kick in, or when in high school, taking the lead in school plays, and learning three hours of dialogue with ease.

The summer of 1957. A pivotal summer in my life, not just my young life, but the whole of my life, the most impactful summer of my near 68 years on this planet. In retrospect, looking back on that summer of what began as misery and pain, and what it has meant to me over the course of the next 60 years of my life — I love my mother for what she did for me.

As I have written previously, and as I will write again, I am who I am because of the tough, caring women who have come into my life, who have been demanding of me to be my best, to give all that I can give.

As is the case with most of the women with whom I have shared my life, my mother was a tough, bright, brooked no nonsense and driven woman, someone you did not want to cross, ever, who was also — not to put too fine a point on the matter — crazy (a consequence of childhood trauma), but a survivor nonetheless, and was in her own way, loving, but in terms of the woman who was supposed to raise me, in large measure and for the most part, absent — save one particular summer, the summer of 1957.