Imagine yourself on this autumn Sunday afternoon during the glorious 40th annual Vancouver International Film Festival. You’ve just walked into The Vancouver Playhouse, where after showing your vaccine card, a piece of picture I.D., and having your ticket scanned — as a PDF on your smartphone (photos of the PDF won’t do), or in hard copy — and having been welcomed by one of the hard working VIFF volunteers, are then ushered into a darkened room with seats all facing forward.

You feel reverent.

You are about to worship at the ‘church of cinema‘.

One hundred years on, cinema has arrived as a form of transcendence, for many replacing the once venerated position held by the church. Think about the similarities: churches and the cinema are both large buildings built in the public space. Both have signage out front indicating what is about to occur inside.

As physical structures, both the church and the independent or multiplex cinema create a sense of sacred space, with their high ceilings, long aisles running the length of the darkened rooms, the use of dim lighting, the sweeping curvature of the walls, and the use of curtains to enhance the sacredness of the experience.

In the church of cinema we take communion not with bread and wine, but with the ritualistic consumption of our favourite snack and beverage.

Consider if you will, the memorable moment when you enter the auditorium to find your perfect viewing angle, allowing you to sit back, relax and enjoy (albeit in 2021, with your mask on). Although you may not receive absolution at the cinema, there is the two-hour reprieve from the burden & peregrinations of your daily life.

As the lights are dimmed, the service begins: The seating, and the opening introduction constitute a liturgy for one and all, not dissimilar to the welcoming ritual that occurs in a church service prior to the sermon.

If you are like most people, you obey an unwritten rule that requires you to be in place in time for either the singing (if you’re in church) or the rapturuous introduction of a film by a Vancouver International Film Festival theatre manager. And, you remain silent while in the theatre, focused on all that is unfolding before you.

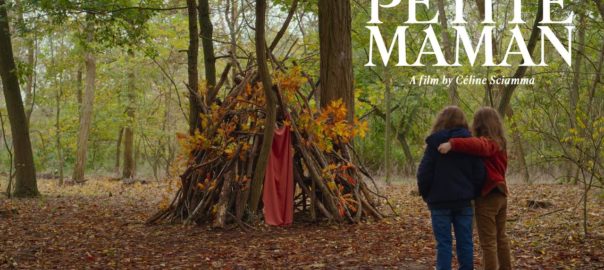

There is, too, the notion that as the film limns your unconscious mind you are being transported, elevated in some meaningful way, left in awe in the presence of a transporting and ever-so-moving work of film art that is screening before you.

What we want from church is often, these days, more of what we receive from the cinema on offer at the Vancouver International Film Festival: the vague, unshakable notion that the eternal and invisible world is all around us, transporting us as we sit in rapt attention. We experience the progress and acceleration of time, as we see life begin, progress, and find redemption. All within two hours. The films at the Vancouver International Film Festival constitute much more than entertainment; each film is a thoughtful meditation on our place in society and our purpose in life.

As a VIFF film draws to a close, just as is the case following a sermon we might hear in church, our desire is to set about to discuss with friends that which we have just experienced. Phrases and moments, transcending current frustrations with a new resolve, all in response to a line of dialogue, an image on the screen or a friend’s comment we have now incorporated into how we will lead our life going forward.

In the holy trinity of meaning, cinema reigns supreme, the personal altar of our home theatres a distant second — although increasingly important in the era of the pandemic — the city providing the physical proof of the reality the other two point to, oriented towards the satisfaction of the devout cinemagoer’s theology.

Throughout the centuries we have sought to find meaning through manifest ritual and symbolism. If, as in the scene from American Beauty, a plastic bag sailing in the breeze is an intimation of immortality then there is, perhaps, something for us to consider respecting the difference between art as diversion and art in our lives as a symbolic representation of an awakened mindfulness, allowing us to not just transcend the conditions of our troubles lives, but change our lives for the better.

For those who have attended the Vancouver International Film Festival over the past 40 years, moving, independent world cinema from all across the globe has emerged as that place where we might experience life in the form of parable, within a safe and welcoming environment, that place where we are able to become vulnerable and open, hungry to make sense of our daily, protean lives.

Cinema, whether it be at VIFF or in the cineplex, delivers for many of us access to the new spiritualism, the place where we experience not merely film, but language, memory, art, love, death and, perhaps even, spiritual transcendence.