At the outset of 1978, Cathy and I moved from the Interior to Vancouver, in order for me to begin a Master’s programme in Education at Simon Fraser University, the Master’s a requirement for me to assume the job of Principal at the school where I’d been teaching for the previous 2½ years.

For Cathy, life in the Interior had proved challenging. While I taught school during the day — my life all but consumed by my teaching and involvement in the politics of the British Columbia Teachers’ Federation — although for a time Cathy had worked at the Ministry of Human Resources in town, it had become increasingly clear that life in a small, Interior rural town was not for her; Cathy wanted what life could offer in a thriving metropolitan centre.

Leaving my job in the middle of the school year was not easy — for the children in my class, for the kids’ parents, for my teacher colleagues and for our friends, all with whom I had become close. If we were to preserve our marriage, though, a return to Vancouver is what was required. For many years, Cathy had sacrificed much for me — now it was her turn.

2182 East 2nd Avenue, in the Grandview Woodland neighbourhood of Vancouver

2182 East 2nd Avenue, in the Grandview Woodland neighbourhood of Vancouver

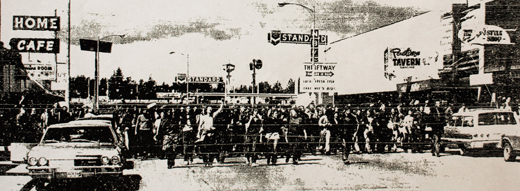

My father had found us a house at 2182 East 2nd Avenue, right across the street from my childhood home, and nearby Garden Park. Our furniture was moved down in two big trucks. I left in the first truck, Cathy in the second truck a few days behind, as she wrapped up our affairs where we had lived for the previous 2½ years. The second truck arrived at our home on East 2nd Avenue on January 1st, our belongings were disgorged from the truck, and preparations were made to set up home in our new surroundings.

Odd thing, though: Cathy never moved into that home on East 2nd Avenue.

Megan was all of eight months old at that time, while Jude was 2½ years. Cathy took Megan, who was still nursing, and moved in with a friend. I was left with Jude. Now, Cathy had a history of long standing for leaving for weeks at a time, only to return home as if she’d never been gone, our relationship returning to the bliss that had almost always been the case.

Although we weren’t living together, we still communicated every day.

Before returning to Vancouver, Cathy had enrolled me in classes at Simon Fraser, and in early January despite the upset of Cathy’s and my unusual relationship, I began school. Cathy was unwilling to care for Jude, would keep Megan only because Megan was still nursing, Cathy advising me to find child care for Jude. I was unable to secure child care for Jude up at SFU, but was able to find child care at nearby Grandview Terrace DayCare (not the child care centre in Grandview Woodland that goes by that name today), on East 7th Avenue, just north of Vancouver Community College. I would drop Jude off at 8am, head off to classes on Burnaby Mountain, returning to pick him up at 5pm. The routine worked, and we were fine.

A couple of weeks into my new school year, and Jude’s tenure in his first child care centre, when picking him up from daycare one afternoon, upon entering the child care facility, I became aware of the supervisor of the centre roughly manhandling a crying three year old boy, and was even more startled to see her slamming the distraught young boy against a wall.

I immediately moved to intervene on the boy’s behalf, expressing grave concern to the daycare supervisor on her rough treatment of the boy. The supervisor turned to me and told me to “Fuck off,” threatening that if I didn’t step back that my own son would be subject to similar treatment.

An aside, in addition to holding a Bachelor’s degree in Political Science, Sociology and Anthropology, I also have a Bachelor of Education, with a specialty in Early Childhood Education, and was granted and held a daycare supervisor’s certificate, awarded automatically to all those graduating with an ECE BEd. I knew what I saw was wrong. I had noticed rough treatment of the children earlier, while dropping Jude off in the morning, but nothing as injurious and alarming as I’d witnessed that chilly, unnerving afternoon.

As I was preparing Jude to leave, putting on his coat and galoshes (it was winter, after all), I witnessed the daycare supervisor pulling a small chair out from under a young girl, and saw the same supervisor kick, yell at and threaten another child. Again, I intervened on behalf of the abused children, and again was told to “Fuck off” by the supervisor. A couple of parents present to pick up their children, and two other child care workers saw both the conduct of the supervisor, our interaction, and her response.

Jude and I exited Grandview Terrace DayCare as quickly as we could.

Upon arriving home, I called Cathy and told her of what had happened that afternoon at Jude’s daycare centre. Here’s what Cathy had to say …

“Pull him out of that daycare, don’t go back there again. Find him new child care.” I expressed concern to Cathy about the welfare of the other children enrolled at Grandview Terrace, to which Cathy responded, “It’s none of your business. You’re always tilting at windmills, looking for problems to fix. You have this ‘save the world’ complex that, although I found it moral in the early years of our marriage, I now find it tiresome. Pull Jude out of Grandview Terrace, find him new child care, and leave it at that. Get on with your life, go to school, and let someone else fix the problem. Jude’s not going back there, so it’s no longer your concern.”

I was dumbfounded at Cathy’s instruction — as my wife of nearly a decade, and given my activism on child care issues, she had to know that I wouldn’t just walk away; it simply wasn’t then and isn’t now and to this day in my nature to walk away when any person, child or otherwise, is in jeopardy.

Within 48 hours I’d secured new child care arrangements for Jude, at Hastings Townsite Child Care, run by a young woman named Sue Stables.

Contrary to Cathy’s instruction to me, I did not forget what I’d witnessed three days previous at Grandview Terrace, on East 7th Avenue. I made arrangements to speak with the Grandview Terrace supervisor, meeting with her one afternoon. Upon entering the facility, I again witnessed her abusing a child, in fact several children, before moving over to meet with me. Again, I expressed a concern respecting her “handling” of the children, and again I was told to “Fuck off.” An unsatisfactory response all around.

I had a list of the Grandview Terrace parent phone numbers, and a Board of Directors membership list. I contacted the President of the Board that evening, and made arrangements to meet with the Board later in the week. I met with the Board, told them of what I had witnessed, expressing concern as to the welfare of their children. The Board members listened intently, with the Board President, a man, finally speaking up, asking …

“What do you want us to do about it? Sometimes children get out hand. Sometimes children need a little bit of rough justice. We know how the supervisor approaches her job, and we approve. Quite obviously, you don’t, and you’ve pulled your child from Grandview Terrace. As a parent group, and speaking on behalf of the Board, we’re quite happy with the existing circumstance, and will do nothing to respond to your concerns, because they are not concerns that we share. Now, if you could just leave so that we can get on with other business, we’d all appreciate it.”

I spoke with Cathy that evening, told her that I’d met with the Grandview Terrace Board, to which she responded angrily, “I told you, it’s none of your business. If the parents are happy with what’s going on, let it go.”

Anyone who knows me would know that I would not “let it go,” never have, never will. Children’s well-being was in jeopardy, and I wasn’t going to walk away. The very next day, I made arrangements to meet with the supervisor of Daycare Information, an office operated by the Ministry of Human Resources. As it happened, I knew the supervisor, a woman with whom I’d worked closely in the co-operative movement some years earlier, and with whom I’d worked toward creating child care in British Columbia.

My friend and former colleague listened to what I had to say, and after asking me a few follow-up questions, she committed to the conduct of an investigation into my concerns. Over the coming months, the two of us kept in touch, working together from time to time. The results of the investigation were published, and made public, in November 1978.

Note should be made that there was no reporting legislation on issues related to child abuse, and the Socred administration of the day was not about to bring in any such legislation. People turned a blind eye to child abuse, including teachers, who throughout the 1970s (and earlier), 1980s and early 1990s in British Columbia were not allowed to report child abuse, or intervene on behalf of a child, as instructed by district administrators, arising from a fear of suit being brought against school districts by irate parents. The same discouraging ethos existed in the realm of child care.

In point of fact, it wasn’t until 1993 in British Columbia that a BC NDP government made it the law that adults witnessing, or who were aware of, child abuse would be compelled by law, and under penalty, to report it.

Here’s what occurred from the time of my reporting to Daycare Information on what I had witnessed at Grandview Terrace Daycare …

1. A Daycare Information staff person was sent to meet with the supervisor, her staff, and members of the Board at Grandview Terrace. Each denied any wrongdoing, and were unco-operative with the Daycare Information staff person, as was recorded in the final report;

2. An undercover investigator was assigned to work at the Grandview Terrace, as a “student” from Langara’s Child Care Programme on a work practicum. The investigator brought both audio and video equipment with them. Over a period of six weeks, video was filmed of the ongoing abuse of the children enrolled in the centre by all three child care staff, as well as by parents;

3. By April, Daycare Information secured a Court Order removing the daycare supervisor and child care staff from the centre, as well as the members of the Board of Directors. An administrator was assigned to run the affairs of the child care centre, and a new supervisor and staff were hired and installed;

4. The Vancouver Police Department and the Ministry of Human Resources worked together to further investigate what had been occurring at Grandview Terrace;

5. In June, the Crown charged the daycare supervisor with child abuse, and child endangerment; the child care staff were charged with child endangerment.

The case was brought to Court in September, the outcome of which was this: the supervisor was found guilty on both charges, but given a conditional discharge and a probationary period of five years. The lawyer for the daycare supervisor and the Crown made a joint recommendation to the Court on the conditional discharge that would stipulate that the supervisor would never again work in any capacity with children, not as a child care worker, a teacher or in any other capacity in which she might come into contact with children. The judge so ordered.

The abusive and unrepentant child care supervisor continued to maintain that she had done nothing wrong, and proved as verbally abusive to investigators as she had been with the children. At no point did the supervisor admit wrongdoing, or come anywhere close to accepting responsibility for placing the safety interests of children in jeopardy.

The two other child care staff were given an absolute discharge, and instructed that they could return to work in child care only if they were to complete a one-year child care course at Langara College, under the strict supervision of the administrator of that programme.

The Ministry of Human Resources apprehended three children who had been enrolled at Grandview Terrace, agreeing to return the children to their parents on the condition that the parents enroll and complete a three-month parenting course provided by the Ministry, their children to be returned only on the satisfactory completion of the course. Such was ordered by the Courts, and it was carried out in full I was to learn later.

The remaining parents who had been aware of what had transpired at Grandview Terrace but had done nothing to intervene to maintain the welfare of the children enrolled at the child care centre were also ordered to take the parenting course, the order also stipulating that each of these latter parents must meet with a social worker from Daycare Information once a week in each of the coming three months.

Throughout the entirety of the process above, Cathy was adamant that, as she said … “You stuck your nose where it didn’t belong,” adding, “I don’t know what it is with this complex you seem to have where you feel the need to rescue the world, but I’m sick and tired of it.”

In the early years of our marriage, the refrain I heard daily from Cathy …

“You are the best person I have ever known. You are kind, and honourable and a good person. I know that anything that you set out to do will be the right thing, the moral thing. I trust your judgement in all matters, I love you, and I will always support you in whatever you do, whatever cause you champion.”

I sometimes think that for the years of our marriage, Cathy created something of a monster, someone who truly believed he could do no wrong — which, as we all know, is impossible, because all of us are fallible, all of us no matter our good intention are likely to commit an act, however unwittingly and however unintended the consequence, will cause someone else anguish and pain, and will disrupt their lives in ways that are hurtful.

As for my activist and leftist friends, none were in the least supportive throughout the entire investigatory process and my involvement in it, as they were focused more on the “bigger picture” of social change and not, as they explained to me, “the picayune concerns of one child care centre.”

And so it is, most often with some activists on the left — it is ideology over practical concern of remediation respecting the lives of individual persons, even children, and their personal circumstance, and their personal pain.

In November, I was contacted by Daycare Information and was told that I was to be given a Humanitarian Award at the Annual General Meeting of the Early Childhood Educators Association, arising from my activism for child well-being. In fact, I was awarded the next month, in early December, where I was called a “hero” by the President of the ECE Association.

Let me be clear: there’s no heroism involved when an activist simply sets out to do the right thing, the moral thing, whatever the trying conditions that might accompany the fight for what is humane and proper, and that which serves the human interests of an individual or groups of persons.

Upon hearing of the proposed award, Cathy was no more happy with me than she had been at the outset, critical and, as it happened, well on her way to divorcing me, now leaving me with custody of both Jude and Megan.

As to my friends there was, as I expected there would be, a round of, “I knew you were doing the right thing. I’m glad to have stood by your side to offer you the support you needed these past months,” which declaration was a re-imagining of the truth, and what had actually transpired.

In the coming years, I would continue to advocate for the interests of children, both on a global scale, and as an educator working in classrooms across Metro Vancouver, often at much expense to myself, and rarely if ever with the support of my contemporaries, nor with Cathy’s support, nor for that matter the support of administrators in school districts in our region.

Throughout my life, I have always sought to do the moral thing, whatever the cost to myself — and, often, it has proved to be at great cost to me.

At month’s end, with great reluctance I will cut back on my ongoing coverage of the 2018 Vancouver civic election, in order that I might work on the correction of a circumstance that has long been of grave concern to me. Once again, I expect little or no support for my endeavours — save, perhaps, that of my friends David Eby and Spencer Chandra Herbert, two of the most moral men I know, good and great on issues of societal concern, and much beloved by many, and just as good on issues relating to personal crises. Both are amazing men of grit and compassion, and I am fortunate to have both men “on my side” — which, as you surely must be aware if you know me at all, is not an easy task, nor one which is entered into lightly.