Human history, since time immemorial, has been undeniably marked by a series of revolutions that helped shape us as modern individuals.

Our whole concept of civilization is determined by a succession of consecutive turning points.

From the early Neolithic Revolution, 12,000 years ago, through the Industrial Revolution of the 18th century and the Jet Age of the 1950s and 1960s, our species has evolved enormously.

In the current age, the Digital Revolution — also known as the Third Industrial Revolution — is the continuous evolution from the previous models of analog, mechanical and electronic technologies to the transformative digital technology with which we have all become familiar in recent years (think: streaming).

In 1993, digital technology revolutionized cinema.

The highest-grossing movie that year was Jurassic Park, whose dinosaurs ironically represented an evolutionary leap. Audiences were wowed by those hyper-realistic digital effects — all six minutes of them.

![]()

Leading up to its release, the 2009 movie Avatar promised to be a record-shattering hit.

In order to capitalize on the blockbuster to the fullest extent, movie theatres around the world got rid of their creaky old film projectors and purchased sleek digital replacements.

While projection technology had been available for a decade, it took the promise of a digital smash hit to convince theatres to adopt it at a large scale.

Before long, digital filmmaking and digital projection had become the industry standard. While it was an expensive investment for theatres, it allowed them to be more nimble in what they screened.

“It’s not a surprise that this transition took place: physical film was particularly inefficient. It’s heavy and it’s expensive,” says University of California, Berkeley marketing professor Eric Anderson. “What was more surprising was how this affected the assortments [of movies] offered to consumers.”

“With digital,” Professor Anderson continues, “it’s easier to have time for niche films, because one employee can manage all the screens in a theatre, and can effortlessly switch between one movie and another with the push of a digital button. Digital technology also gives the theatres more flexibility to stream big blockbusters even more. In a study conducted recently, it was interesting that we found these two effects together.”

The very first fully digital film, Star Wars: Episode I — The Phantom Menace, was screened in Los Angeles in 1999. But it took time for theatres to switch over, in part because the new equipment was so expensive.

A single digital projector could cost as much as $150,000 — an eye-popping sum for a theatre with eight screens to convert.

As a result, Anderson says, theatres “fought the change as much as they could until it was shown to them very clearly that the economics made sense.”

Initially, there was little urgency.

From 1999 until the early 2000s, relatively few films were released in a digital format — mostly big-budget offerings, such as Star Wars and Toy Story 2.

Converting came with a host of benefits: the film era required the creation of costly physical copies of movies. The number of times per day a theatre could screen a hit movie was limited by the number of copies they had.

Film also posed logistical challenges: each movie required several reels that were heavy and hard to manipulate, and the process of switching between movies on a projector was time-consuming.

As a result, theatres tended to show only one movie per screen each day. Digitization changed all that, making it effortless to offer more movie variety to consumers.

Still and all, the financial crisis of 2008 continued to slow the transition to digital by making it difficult for theatres to borrow the capital they needed to upgrade their equipment.

But Avatar “acted as a rallying point to get the industry to transition, which James Cameron pushed very hard for,” Anderson explains.

As the highest grossing movie of all time, Avatar was also the first 100% digitally photographed “film” to win an Academy Award for Best Cinematography.

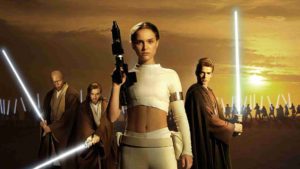

Not since George Lucas’ Attack of the Clones had a director tried to fundamentally change the cinema-going experience and, love him or hate him, James Cameron meant to do just that.

Cameron immersed audiences in the alien world of Pandora by incorporating ground-breaking 3D along with the digital Fusion Camera System to capture his vision, ushering in the final shift towards digital cinema for the majority of movie productions.

From that point on, the conversion process picked up momentum; 90% of movie screens worldwide had gone digital by 2015.

The true effects of the digital transformation became apparent and overall movie variety increased. Smaller theatres with four or fewer screens saw the most noticeable increases, about 11%. In larger theaters, the percentage of screens devoted to blockbusters increased during weekend hours, but decreased on the weekdays, resulting in greater variety during these less-popular times.

In other words, theatres prioritized blockbusters during peak periods and “offered slightly more variety or more niche films during off-peak periods,” Anderson observes. “It’s a more efficient use of their screen space, given the ebb and flow of consumer demand.”

As filmmaker John Boorman noted in a 2023 article in The Guardian, “Steven Spielberg’s The Fabelmans was the only Best Picture Oscar nominee this year shot on celluloid.”

“For more than 100 years, films have been made of film,” Boorman observes. “Now, instead of a magazine being loaded on to the camera, a card is inserted that electronically records whatever the camera sees.”

“Today, most ‘films’ are made electronically,” says Boorman. “No film is used in the making of them — not the shooting, editing or projection. So they can’t — or shouldn’t — be called films.”

Change, as most of us know, is constant, and inevitable, if in the eyes of cinema purists, “regrettable.”

Perhaps the time has come to change the language we employ to describe what we see at the cinema, or on our screens at home.

Unless a new picture is actually made of film, it should not be called a film.

Perhaps, going forward, we should refer to it as a …