From the earliest days of Hollywood, women were stage managed and manipulated by older men in powerful positions. And it remains clear that, although Harvey Weinstein, Les Moonves, John Lasseter, Luc Besson, among a host of other male predatory Hollywood executives who have been outed, little good has been achieved still for women in the film industry.

In the Hollywood dream factory, trauma surfaces as light entertainment.

In 2013, introducing the list of best supporting actress nominees during the Oscar ceremony, actor and comedian Seth MacFarlane quipped: “Congratulations, you five ladies no longer have to pretend to be attracted to Harvey Weinstein.” What was chilling was that no one got the joke. The idea that female stars and aspiring, often young, female stars are required to accept the attentions, at the very least, of older male studio executives, producers and prominent male stars, is as old as the Hollywood hills.

Given the profile that the #MeToo movement has brought to sex discrimination, why does sexism continue to prevail in Hollywood?

According to San Diego State’s Center for the Study of Women in Television and Film, women made up only 7 per cent of directors on the top 250 films of 2018, which was actually a 2 per cent decline from 2017. The same study found that while women made up higher percentages of other fields in the industry — 24% of producers, or 17 per cent of editors, for example — they only accounted for 17 per cent of the workforce of all the jobs surveyed. And that too, was a 2 per cent decline from the year before.

The University of Southern California’s Viterbi School of Engineering’s Signal Analysis and Interpretation Lab (SAIL) revealed how sexism is embodied by characters on the silver screen. If female characters are taken out of the plot, it often makes no difference to the story the study found.

Analyzing 1000 scripts, the study found that there were seven times more male than female writers & twelve times more male directors than women.

The biggest impact in counteracting the gender imbalance was if female writers were present at script meetings. If this was the case, female characters on screen was around 50% greater.

Inherent in these observations of the film industry are powerful messages about what it means to be female.

In our “post-feminist” era, where we are frequently told the problems of girls are yesterday’s news — that girls are awash in the largesse of civil rights, and it is boys who really require our attention — it is worthwhile to consider the conduct of male Hollywood writers and executives.

Actress Geena Davis, founder of the Geena Davis Institute on Gender in Media

Actress Geena Davis, founder of the Geena Davis Institute on Gender in Media

The problem is so glaring that in 2005, the actress Geena Davis, who would go on to start her own gender institute, commissioned Stacy Smith, a researcher at the University of Southern California, to study the issue and help push the studios beyond the staid male-centred film industry.

From 2007 through 2017, according to Smith’s research, women made up only 30.2% of speaking or named characters in the 100 top-grossing fictional films.

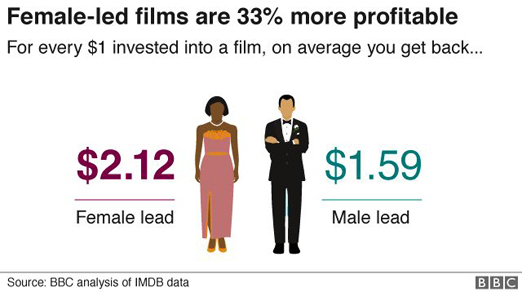

The Geena Davis Institute on Gender in Media reports that films featuring women are financially profitable. “Guess what, Hollywood? Female-led films consistently make more money, year over year,” Madeline Di Nonno, the Institutes chief executive has reported to the heads of Hollywood studios.

Hollywood actor Charlize Theron has criticized the movie industry for gender bias. Promoting her film Atomic Blonde, she told feminist Bustle magazine: “Fifteen, ten years ago, it was almost impossible to produce female-driven films, in any genre, just because nobody wanted to make it.”

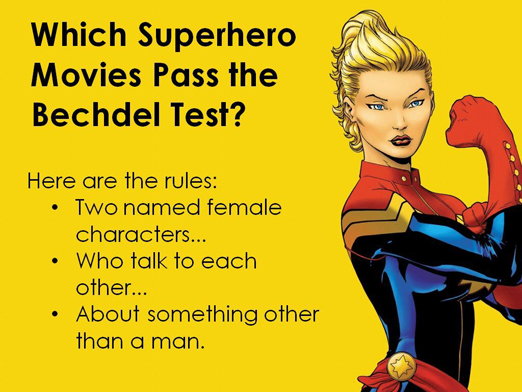

A quiz that was designed to find out how sexist a film might be was developed by Alison Bechdel and Liz Wallace in 1985. To pass, the film needed three positive answers to these questions: Does it have more than two named female characters? Do those two talk to each other? Is that conversation about something other than a man?

The Hollywood Reporter applied the Bechdel-Wallace test to the top-selling movies of 2018, finding that only around half of the films passed the test.

Actress-writer-director Lena Dunham, creator of the HBO series, "Girls"

Actress-writer-director Lena Dunham, creator of the HBO series, "Girls"

Female directors are in what “Girls” creator Lena Dunham calls “a dark loop.” If they don’t have experience, they can’t get hired, and if they can’t get hired, they can’t get experience. “Without Googling it,” Dunham asked a recent Sundance panel, “Ask anybody to name more than five female filmmakers who’ve made more than three films. It’s shockingly hard.”

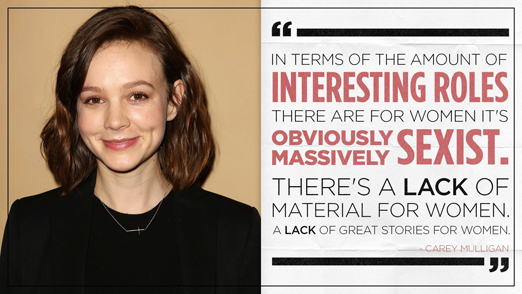

The sheer scale of rampant Hollywood sexism is daunting, the stories of what actresses have to put up with disturbing, the tales of pay inequity and pushing for more female-led stories are instructive.

Actress-writer-producer Zoe Kazan, star of the Oscar-nominated film Big Sick, and writer and executive producer of the films, Ruby Sparks and Wildlife (the latter now on Netflix)

Actress-writer-producer Zoe Kazan, star of the Oscar-nominated film Big Sick, and writer and executive producer of the films, Ruby Sparks and Wildlife (the latter now on Netflix)

Actress Zoe Kazan (The Big Sick) told IndieWire reporter, Kate Erbland, “There’s so much sexual harassment on set. And there’s no HR department, right? We don’t have a redress. We have our union, but no one ever resorts to that, because you don’t want to get a reputation for being difficult.”

The Oscar winner and star of The Favourite, Rachel Weisz, told Out Magazine that a number of her male co-stars have taken lower salaries in order to match her own. “In my career so far, I’ve needed my male co-stars to take a pay cut so that I may have parity with them,” she said.

Actress Emmy Rossum sounded off during a recent Hollywood Reporter roundtable about her experience with overt sexism in the industry.

“I’ve never been in a situation where somebody asked me to do something really obviously physical in exchange for a job, but even as recently as a year ago, my agent called me and was like, ‘I’m so embarrassed to make this call, but there’s a big movie and they’re going to offer it to you. They really love your work on Shameless. But the director wants you to come into his office in a bikini. There’s no audition. That’s all you have to do.'”

If the dynamic of older men and younger, submissive women greases the wheels of Hollywood production offices repeats itself on screen, it is not an accident, but the desires of the producers and directors who create these films played out on the biggest stage of all: Hollywood cinema, the world’s most effective propaganda machine. Who is Hollywood trying to kid?